Ray's article

To provide context for this article, we briefly want to

describe a traditional state approved construction apprenticeship program. It

is important to note, however, there is significant variation in both the rules

and practices across different states apprenticeship programs. Overall the federal

Department of Labor regulates and supports apprenticeship programs.

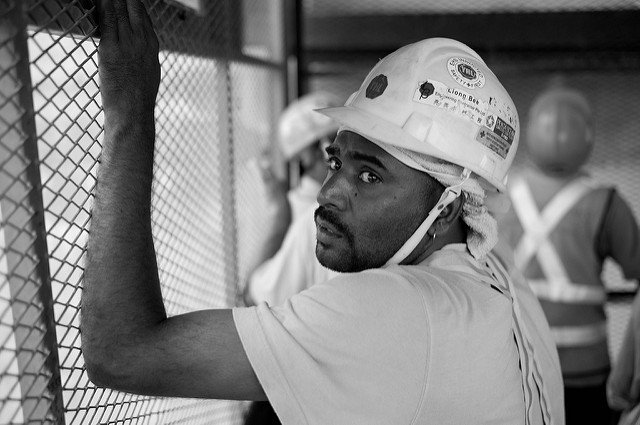

Apprenticeship programs prepare individuals for careers in various trades (mostly

in construction) using a combination of on-the-job training and course work. For example, highway trades are a specific

subset of construction work that include trades such as laborers, equipment

operators, carpenters, and cement masons. This work is generally outdoors and

physically intensive. Apprenticeship programs may be union based (i.e., all

apprentices are members of a union and employers hire only apprentices from union

programs) or “open shop” (apprentices are not union members and work for employers

who hire nonunion workers).

The American construction industry has traditionally been

marked as a very physically intense occupation and has largely been occupied by

white male workers. Although, black labor has always played a major role in the

construction of America, predating the founding of the United States, black men and black women entering the trades today experience racialized employment

practices during their apprenticeships.

It has been a well-documented fact that in the United States black tradesmen and tradeswomen have experienced harassment based on race/ethnicity

in the construction industry at appalling levels. As a black tradesman myself, who has completed a

construction apprenticeship, I would agree without exception that the hardest

part of working in the trades is not the job, but dealing with prevailing attitudes

about blacks not belonging in the trades, even at the union level.

DISCRIMINATORY

HIRING PRACTICES

Let’s discuss where the racial discrimination in the

construction hiring practice begins. A study by Roger Waldinger and Thomas

Bailey published in Politics and Society, titled “The Continuing Significance

of Race: Racial Conflict and Racial Discrimination in Construction.” argued

that black tradesmen have not attained significant inroads into construction

workforce because of the informal hiring and training practices and resistance

from unions.

In order to be accepted into an apprenticeship program,

individuals typically must be 18 years of age and hold a high school diploma or

equivalency certificate. Apprentices choose an apprentice program that will

train them in a specific trade. An apprenticeship program typically takes two

to five years to complete, depending upon the requirements of the program and

the availability of jobs. Yet, most union and non-union apprenticeship programs

do not advertise these openings in the black community nor do they conduct any outreach

programs in majority black high schools to recruit black youth.

While all apprentices are required to complete a set amount

of on-the-job training hours and course work, which differs by apprenticeship

program, the majority of apprenticeship programs training centers are often

located far from major black cities and suburbs. The distance an average black construction apprentice travels to training often creates a logistics issue. Some training centers are located more than 50 miles from black suburbs.

Apprentices attend classes ranging from basic math and

construction safety to specialized classes for their chosen trade. The

on-the-job training provides apprentices with hands-on experience under the

guidance of a journeyworker (a skilled craftsperson who completed an apprentice

program). Attaining the necessary training

on job sites is pivotal to apprentices’ success in the program and their ability

to become journeyworkers or journeyman.

And, since on the-job training is a critical counterpart to

classroom training, surmounting the racial discrimination and getting the

training is a necessity, yet an unnecessary burden for black apprentices. Aside

from the racist comments and graffiti which are so pervasive in modern American

construction culture, black apprentices also face ongoing issues with finding

work and being assigned to low-skill tasks.

In a study conducted by Kris Paap in a Labor Studies Journal

article, titled “How Good Men of the Union Justify Inequality,” found that black

tradesmen did not receive the informal mentoring on the job site that white tradesmen

received. In addition, black tradesmen were more likely to be perceived as lazy

or bad workers and they were more likely to be blamed when mistakes were made.

When a person applies to an apprenticeship program, they are

ranked based on various criteria, which varies from program to program.

Programs have an interview or a “point system,” which scores aspects of the

written application to document completed course work and previous work

experience. Some union apprenticeship

programs require the apprentice themselves to find an employer to write them a ‘Sponsorship

Letter’ which grants them entry into a labor union, upon paying entry dues.

The problem with this form of recruiting is many black

apprentice complain of discrimination while seeking sponsorship, and also complain

that their past work experience is often over looked and they are hired at

lower pay rates. For example, a tradesman or woman with 3 to 4 years of

documented work experience should be sponsored into the union as a Journeyman

or Journeywoman, but for many experienced black tradesmen with professional

experience this is not the case.

“I had 6 years of piping and plumbing experience but when I

entered the apprenticeship I was indentured in as a 1st level

apprentice, they tried to bring me in as a pre-apprentice, but I said hell naw.

A lot of guys with family connections, especially the white boys, come in as

Journeymen getting $38 an hour. I persevered and I’m a journeyman now.” - Jim, Journeyman Pipefitter, completed

program.

Those that do become sponsored or accepted into a

construction apprenticeship are put on an“eligible list” that determines the

order in which apprentice’s access jobs. As jobs become available with “training

agents” (employers associated with the apprenticeship program), applicants at

the top of the list are called and registered as apprentices. When apprentices

complete a job or are let go for any other reason by their employers, they are

put on an “out of work” list that ranks apprentices by time out of work (a

version of the out of work list is used by many, but not all, apprentice

programs).

As job opportunities arise, apprentices are called based on

the order of the list. However, as will be discussed below, construction

companies can circumvent the out-of-work list in order to maintain steady

employment with their “regular employees”.

While on-the-job training is a required part of

apprenticeship program, work is not always immediately available and jobs are

not guaranteed. One of the most prevalent issues effecting black tradesmen and

tradesmen is a lack of network, a network that they control, and a network that

they can depend upon for job opportunities. We will discuss this further below.

Construction is a cyclical industry and apprentices may be out of work for days, weeks, or months at a time. But, once the classroom work and on-the-job hours are complete, apprentices “journey out” and become journeyworkers or journeymen, who have the credentials, skills, and experience necessary to work in their designated trade at the highest pay scales. Journeymen can work unsupervised and are responsible for training new apprentices. They often go on to become foremen, supervisors, or superintendents.

There are many aspects of apprentice programs that are (on

the surface) equitable and race neutral: apprentices are accepted into programs

using standardized criteria; in some apprentice programs, jobs are assigned

using an out-of-work list; in some apprentice programs, employers are not

allowed to request specific apprentices; employers may not turn down black

workers or women; and apprentices at the same level are paid the same wage

(thus eliminating the possibility for a gender or racial/ethnic wage gap

between workers with equal experience). However, drawing on many studies we

examine how racial/ethnic inequalities still persist in apprentice programs,

despite these apparently race-neutral policies.

Today, across the United States, the construction workforce

as well as apprenticeships primarily consists of white males, and some states

have sought to diversify recently targeting funds intended to encourage “women”

and so-called “people of color” to enter into the trades; but no state has created

any programs that specifically increase retention of black workers, primarily

apprentices. Black apprentices across the United States remain a small portion of

new apprentices and there are continued issues with retention of these black men

and black women. As noted above, there are many aspects of apprentice programs

that are (on the surface) equitable and race neutral.

GOOD OLD BOYS CLUB

As stated above, the construction industry is a white male

dominated industry. In our study understood the apprenticeship system (and the construction

trades more broadly) to be a “good old boys’ club” (a combination of the

phrases “old boys’ club” and “good old boys”), that is, an occupation dominated

by working-class white men and built upon relationships among these men.

The experience of many black apprentices in the trades as a

“good old boys’ club” has resulted in subtle (and sometimes not so subtle)

exclusion and harassment. The discrimination that some black apprentices face

has damaged their access to relationships with journeymen, foremen,

supervisors, and other workers on their job site. This, in turn, has affected

their opportunities to be mentored and ultimately their ability to remain

consistently employed.

Apprentices are more likely to be successful if they are

able to remain more steadily employed, either by staying with a company and moving

from project to project (avoiding the out-of-work list) or by limiting their time

on the out-of-work list and finding work quickly after being layed off.

Statistically, across the United States black male

apprentices accrue fewer work hours per month than white male apprentices. Too

much time unemployed between jobs is a major factor that often deterred many black

apprentices from completing their apprenticeship programs. Many black

apprentices believe that the frequent layoffs are purposefully done to make it

difficult for black apprentice to compete.

Speaking under anonymity, a current black male union

carpentry apprentice told Blacktradesmen.us that, “I did everything right, I

passed all of my inspections, I showed up 30 minutes early everyday, I brought

my own water, I never got a safety violation, but they two checked me. I just

did my job, but that wasn’t enough, with all the stupid black jokes they made

it wasn’t worth it.”

Two checks meaning ‘layed off’, an expression used throughout the construction industry on describing how a foreman or superintendent fires a tradesman by providing him with both of his payroll checks, severing all relationships.

One specific problem that some black apprentices face in the course of their on-the-job training, they did not have opportunities to learn all the varied skills they needed to be successful journeymen, as a challenge to completing their apprenticeship. While some studies show, black workers were the most likely to identify doing repetitive or low-skill tasks, while white men were the least likely of all groups to be assigned repetitive or low-skill tasks (such as cleaning the site or flagging traffic).

YOU’RE NOT LAZY!

The legitimacy of a lack of black apprentices in the trades

is bolstered by a reliance on the belief that success is primarily due to hard

work. While apprentices articulate the many challenges that they face, when

specifically asked why some apprentices do not succeed in their apprenticeship program,

“not working hard enough” or “being lazy” were consistently given as the

primary reason by apprentices. But the perception

of who “workers harder than others” is often bias based upon racial stereotypes.

“Head down, ass up. Pretty much. They just got to stay at

it. You can’t be lazy about it. You have to stay working, you have to stay

busy.” (Dave, Black male, completed apprenticeship)

Apprentices with a “poor work ethic” or perceived as working

not as hard as others on the job site, or those that would not (or could not)

learn the necessary skills, and those who had a bad attitude at work are most

often equated with being “lazy.” The stereotypical label of “laziness” has plagued

black workers since slavery, and is one of the most prevalent stereotypes used

against black workers today.

BUILD A NETWORK

The importance of black tradesmen and tradeswomen to network

and build strong relationships amongst one another is key to their success. The

lack of network and industry connection has made things harder for black

apprentices who are frequently out of work. The lack of a brotherhood outside

of the “union brotherhood” is missing for black tradesmen and women. Since

forever, networking in construction is an essential aspect you must develop.

Relationships and connections within an apprentice’s network

are important to have more opportunities to advance their careers. Attending union

meetings and social events are also important apprentices seeking to advance

their industry connections. www.blacktradesmen.us

is also a great tool to connect with people in their field.

The pervasive harassment (particularly racial discrimination) that black Americans in construction face as well as the strategies they use to respond to negative experiences at work is hurting black tradesmen and women fighting to complete construction apprenticeship programs and reach the status on Journeyman or Master level professionals. The lack of an internal network can exacerbate this condition for black apprentices.

We hope that our on going research adds to an understanding of

how organizational policies and discriminatory practices, are causing in racial

inequalities in construction work organizations

In exploring the experiences of black apprentices, we contribute to an evolving understanding of how apprenticeship programs across the United States works. Through assessing these processes, we hope to contribute to conversations about the changes in the construction industry as well as broader policy debates aimed at addressing racial/ethnic inequality in the industry.

Last week the City of Oakland hosted their first of a series

of three ‘community engagement meetings’ to discuss the future of construction

development in the city’s urban communities.

Bay Area building trades unions are expected to back the

implementation of a ‘Project Labor Agreement (PLA) or what is also referred to

as a ‘Community Workforce Agreement’ (CWA) that would require developers to

hire only union labor and contractors for projects that are built on Oakland

city-owned land and or any project that involves city funding.

Local area black contractors and black tradesmen attending the

first outreach meeting last Thursday in East Oakland were concerned that they would

be excluded from job opportunities on future city projects in their own

neighborhoods and surrounding areas, if a PLA was implemented without

protections to black tradesmen and companies.

Speaking at the first

city held meeting, according to Post News, black contractor Eddie Dillard said,

“A Project Labor Agreements benefits white contractors. 90% Black contractors

are non-union.”

Many bay area building

trades unions, who dispatch workers to projects have been historically

segregated, and majority white organizations, admitting almost no Black

workers. And historically, these labor unions have been unwilling to release

data on racial composition within its workforce.

“We have been

asking the unions for 10 years how many African American members they have,

but they have refused” to release the data, said Dillard.

Most of those

locals “have zero Blacks in them,” Dillard said.

Union training

programs are not located in Oakland but in outlying areas, like Benicia and San

Jose, he said. “We have been asking the unions for 10 years how many African American members they have, but they have refused” to release the data,

Dillard said.

The construction industry in Oakland and across the United

States has a long recorded history of racial discrimination within its

workforce. Oakland, CA has a long history of black tradesmen and contractors

fighting for the fair treatment of their brothers and sisters in the trades,

such as

Construction is hands down one of the most lucrative and

rewarding careers for young black men in the United States without a high

school, but yet thousands of them have been discriminated against, and in some

cases completely locked out of an industry that their black forefathers

spearheaded in America 400 years ago.

Recently, the

unemployment rate for black people in the Bay Area reached an alarming 19% just

6-years ago, according to 2013 U.S. Census Bureau data, and although the

unemployment rate has gone across the state, many black Oakland residences have

not felt the change.

In contrast, a 19%

unemployment rate for white workers would be declared a city emergency if that

data was true.

While a traditional

PLA could benefit the over 30 unions in Alameda County, black construction

tradesmen and contractors are worried that if the PLA agreement is improperly implemented it would further solidify

the staunch racism and discriminatory hiring practices running amuck in the Bay

area construction trades unions.

The Oakland city council is expected to come to some type of agreement with the politically powerful labor unions and implement a PLA. Currently, there is no formal Project Labor Agreement (PLA) on the table for the city to consider.

But what about the

black working class citizens of the city, the voters, the black men and women

who build the city and are pushed to the wayside thru racist practices?

Darlene Flynn, director of the Department of Race and Equity

in an interview with the Oakland Post,

said “in evaluating how an agreement might be written to produce more equitable

outcomes, we need to look at the barriers, and it’s best to talk to those who

are closest to the challenges.”

In fact, cities and states are increasingly adopting

“targeted hire” standards and pre-apprenticeship programs to ensure that local

residents and historically disadvantaged black residents, low-income residents,

and residents with past involvement with the criminal justice system are able

to obtain construction jobs created with the support of public expenditures.

San Francisco, for

example, has significantly expanded access to publicly supported construction

projects by mandating that local residents complete 30 percent of a project’s

total work hours and 50 percent of its apprenticeship hours as well as by

partnering with industry, labor, and community nonprofits to create an 18-week

pre-apprenticeship program.

And the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation

Authority adopted a policy in 2012 that requires that 20 percent of employees

on construction projects be apprentices and that 10 percent be from

disadvantaged communities.

However, President Trump is undermining the power of these

sorts of programs to raise standards for working people. In 2017, the Trump

administration announced that it was ending a pilot program at the U.S. Department

of Transportation that allowed communities to establish local hire preferences.

Often acclaimed as effective, pre-apprentice

programs have been a way for construction companies to pay workers less for the

same work, and is also a way for some non-profits to act as a gate-keepers to

the construction industry, often assigned with the task of filtering through potential

black tradesmen to find the best candidates for entry level work that tradesmen

of other races are outright hired for without completing a ‘Pre-apprentice

program.’

Currently, the Trump administration is establishing a parallel apprenticeship system that will allow third-party industry groups outside of the construction trade unions to develop construction apprenticeship programs accredited by institutions approved at the Federal level by the Department of Labor.

And although sometimes

effect at recruiting talented black tradesmen and women, these types of pre-apprentice

and apprenticeship programs do not help veteran black tradesmen and women at

all remedy work force discrimination they encounter on a daily basis at

job-sites across the U.S.

And although

President Obama took executive action to ensure that companies comply with wage

laws, and anti-discrimination protections before they receive federal

contracts, President Trump signed legislation to roll back some these

protections before they were fully implemented.

Lawmakers in Congress should require companies that apply

for federal infrastructure funds to report on their record of compliance with

workplace laws. If they have a poor track record, lawmakers should require them

to come into compliance before they are able to receive any federal funding.

In Oakland, “These

are questions that need to be asked and answered,” said Flynn.

“In these meetings, we are trying to find out who has been

affected, what their experiences have been, who might benefit and whether they

ran into barriers that have resulted in the disparities that we see, looking at

how we can incorporate ways to offset these barriers,” said City of Oakland

Employment Services Supervisor, Jonothan Dumas, according to Post News Group.

Some of the questions

the city wants to address:

*Should a defined

percentage of the hours on city projects go to local workers (such as 50

percent)?

*Should there be a

requirement to hire the formerly incarcerated?

*Should some of the

jobs be reserved for people who live in certain Oakland zip codes?

*What should be the

requirements for hiring local apprentices?

*Should there be

funding for training and removing barriers to employment?

The next community

engagement meeting will be held Saturday, Aug. 10, 10 a.m. to noon, at the

West Oakland Youth Center, 3233 Market St. in Oakland.

In conclusion, while

community organizations, labor organizations, training intermediaries, and the

public workforce system have made significant progress in recent decades to

expand access to construction trades, more must be done to organize black workers and expand the scope of

high-quality apprenticeship programs and increase access and pay for

historically disadvantaged black communities.

Apprenticeship programs can and should be a broadly

accessible path to high paying careers that pay a living wage. However,

currently, too many workers, particularly black/African American workers - face

difficulties accessing these programs, especially the programs that pay the

highest wages.

The U.S. system of registered apprenticeship has been responsible for putting more Americans into the middle class over the last 80 years, than any other form of education in the U.S.

Apprenticeship is, hands

down, the country’s most effective education and employment model, especially

for the construction industry. Imagine earning a quality education, graduating

with no debt, and transitioning directly into a career paying more than $60,000

a year, this is a reality for most apprentices in America.

But, in contrast to the German and Swiss apprenticeship

systems, where upwards of half of all young people, millions of them are

prepared for a range of careers through apprenticeship; whereas the American

system serves just over a half a million apprentices in any given year, and

prepares them primarily for careers in the skilled trades.

Aside from the traditional construction related apprenticeships, the Trump administration over

the past 2 and a half years has embarked on a mission of expanding

apprenticeship programs into new industries, such as health care and

information technology, with a goal of better connecting these apprentices to

higher education.

The Trump administration in fact, is building an entirely

new system of ‘industry-recognized apprenticeship programs,’ or IRAPs.

TRUMPS IRAP’s ARE

EXPECTED TO CHANGE THE GAME

IRAP was born out of President Donald Trump’s 2017 Executive

Order to Expand Apprenticeship in America.

In section 8 of the order, the Secretary is directed to establish a Task

Force on Apprenticeship, bringing together industry and workforce leaders to

consider how to promote apprenticeships especially in sectors where they are

insufficient.

The Presidents program is designed to expand apprenticeship

opportunities and give business more say in crafting training programs.

Although the construction industry is lacking trained, qualified skilled

workers at a record number, in its roll out, the administration will exclude

the construction industry from participating in the IRAP.

Effectively, privately ran IRAP’s will massively overhaul

apprenticeship regulations, and be governed by a distinct set of new

requirements, and quality-assurance processes that, the administration argues,

will make it easier for sectors like IT and health care to adopt apprenticeship

programs, and closely institute them under federal employment guidelines, such

as anti-discrimination policies which for years have been outright ignored by

some unions and privately recognized apprenticeship programs.

As the Trump administration continues to make investments

necessary to grow apprenticeship programs, their policies must center on

helping black workers, and other underrepresented groups to ensure equitable

access.

There is a lack of resources and social networks in the

black/African-American community to get into many high paying jobs, especially

those that lead to long-term careers like the one’s apprenticeships provide.

Apprenticeship programs offer one of the few career pathways

to people without college degrees, with few skills or with criminal records.

But entry into union ran apprenticeship programs are extremely competitive.

For the highest-earning apprenticeship programs, like electrical and sheet metal work, applicants must pass an entrance examination that tests math skills, among other abilities, and then interview for these positions under adverse scenarios, many times battling internal hiring practices such as nepotism.

This is why the Trump administration and the DOL

must include the construction industry into it’s IRAP initiative.

BLACK APPRENTICES FACE DISCRIMINATION

Although, Registered Apprenticeships are apprenticeship

programs that are registered with the DOL and are governed by regulations laid

out under the National Apprenticeship Act.5, and although these regulations lay

out labor standards for these programs and govern their Equal Employment

Opportunity (EEO) rules, many black/African American apprentice file

complaints, and lawsuits claiming damages due to massive amounts, and sometimes

organized acts of discrimination and exclusion from federally recognized

apprenticeships.

Currently, EEO rules prohibit apprenticeship sponsors - typically employers or unions—from engaging in discrimination, as well as require them to take affirmative steps to ensure EEO, including efforts to recruit from a broad pool of potential apprentices. Furthermore, programs with five or more apprentices are required to develop a written affirmative action plan and conduct an apprenticeship utilization analysis to ensure that they are drawing adequately from the local pool of available workers.

Yet in 2017, 63.4 percent of individuals who completed

Registered Apprenticeship programs were white, 10.7 percent were Black/African American, and 20.5 percent did not provide their race to their

Registered Apprenticeship sponsor at all.

According to many studies, one challenge in identifying

trends in apprenticeship participation by ethnicity and race is that the share

of those who do not provide their ethnicity or race. The lack of reporting has

increased significantly over time with Hispanics, with 29 percent of Hispanic

apprentices refusing to provide their Hispanic ethnicity in 2017—up from 3.3

percent in 2008.

Policymakers insist that this issue should be resolved immediately as more accurate data on the racial and ethnic composition of apprentices are necessary to conduct a fair equity analysis.

BLACK APPRENTICE FACE

UNFAIR COMPETITION

In many cases after completing stringent and intense union

ran apprenticeships, black/African-American apprentices find it difficult to

find work.

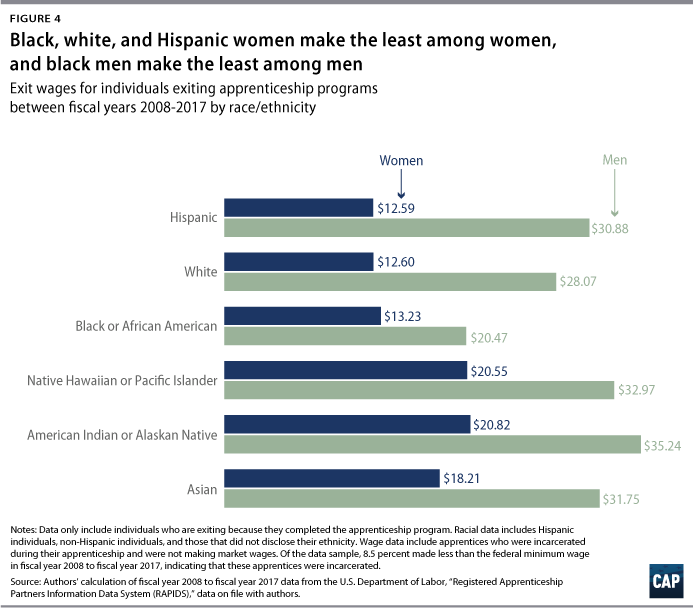

Black/African American apprentices had the lowest exit wages

of all racial and ethnic groups examined, at $14.35 per hour in fiscal year 2017.

White apprentices had the second-lowest earnings at $26.14; although white apprentices earned more than 50% more than Black/African American apprentices’ wages.

Median wages for Hispanics/Latinos completing apprentices

were the highest as they earned around $30 per hour.

One of the reasons that wages for Hispanics/Latinos apprentices are so much higher may be that they are more likely than black and white apprentices to complete their apprenticeship programs in Western states versus the south.

From fiscal year 2008 through fiscal year 2017, exit wages

for apprenticeship programs were highest in Western states at $32.50 and lowest

in the Southern states at only $20.80.

DACA

Another reason for the huge difference in wages amongst Black and Hispanic apprentices can also be attributed to large populations of 'non-citizen Hispanic' workers in Western states that are participating in the workforce,aat the union and non-level.

Many DACA recipients are also members of union ran apprenticeships, using employment

authorization cards (work permits), often issued through the Deferred Action

for Childhood Arrivals program known as DACA that President Barack Obama created

in 2012.

The DACA program, which was established without congressional approval, has protected 670,000 undocumented immigrants from deportation and enabled them to get work permits, and enter into apprenticeships, these people are commonly referred to as 'DACA recipients'. or'Dreamers.'

This work permit not only gives illegal alien workers the right to work in the U.S., it also creates unfair competition for native born, foundational black American apprentices seeking employment in the same trade fields.

The Trump administration and his justice department is preparing to end the DACA program altogether, which has prompted the Supreme Court to intervene, the court’s decision on rather its lawful for Trump to end the DACA program iexpected to be decided in the midst of the 2020 presidential election.

HOW WILL TRUMP

FIND FUNDING FOR IRAP’s?

“I don’t think

there’s going to be any takers because there’s no money,” a trade group

lobbyist told Bloomberg Law.

The Labor Department’s (DOL) announcement about the

implementation of this new nationwide apprenticeship program has some unions

and trade groups at arms with the department. Although the Trump administration

has not allocated any federal funding for these IRAP’s, that may be changing,

as it seems increasingly likely that the IRAP programs will become eligible for

federal funding.

According to Bloomberg Law, the Labor Department has a few

places where it can look for cash to fund IRAP grants if Congress decides not

to specifically appropriate money for the program.

That includes using funds allotted for the H-1B visa

program, which the DOL has wide latitude to spend as it sees fit. The H-1B visa

program offers temporary employment permits to foreign workers in the U.S. tech

jobs and other specialized occupations.

President Trump has mentioned his planned overhauls for the

H-1B program in the past, and has stated that he may reallocate funds from this

program to benefit American workers thru IRAP’s. In fact, late last summer, DOL

issued a funding opportunity announcement (FOA) outlining $150 million in grant

awards for apprenticeship programs, derived from fees paid by employers to

sponsor H-1B visas for workers coming from abroad.

Congress, both republicans and democrats, continue to demonstrate

their support for expanding apprenticeship programs. In 2016, DOL received $90

million in the first-ever congressional appropriation targeted specifically at

apprenticeship expansion. Since then, this amount has climbed steadily—$95

million in FY 2017, then $145 million in FY 2018, then $160 million in FY 2019.

And, although the Department of Labor has established that

IRAPs will not initially affect the construction industry or military apprenticeships,

many labor unions see IRAP’s as a future threat to their long established apprenticeship

programs.

UNIONS PREPARE FOR

WAR

Jim Reid, the apprenticeship director for the International

Association of Machinists, said the DOL’s efforts to fast-track the establishment

of IRAP’s has purposefully left out many union voices.

While many unions and trades groups are arguing that

privately ran IRAP’s pose a threat to their established apprenticeship programs, that have been historically white,

many others argue that IRAP’s will offer opportunities, and specialized training

to black workers that are employed more than 50% as non-union workers, and are

excluded from union ran apprenticeships at alarming numbers.

Worried that IRAP regulations and accrediting standards will

eventually crossover into the construction industry, many labor unions are

warning the Trump administration against such action. Union representatives are

warning Trump that if his administration winds up breaking from its commitments

to exclude construction in the proposed rule, the building trade unions are

prepared to abandon their support of Trump.

A brief look at many labor uniots twitter and Instagram pagess over the weekend show that union leadership is preparing to mount a public campaign attacking IRAP’s and the administration for what they feel will undermine union-protected wage and safety standards, a building union lobbyist told Bloomberg Law.

At the moment some White House officials have been advocating for construction industry inclusion, a reversal on what Trump initially proposed, analit is alienating the blue collar organized union labor groups that Trump has been, and will be counting on for support in his 2020 re-election bid.

In it’s current form, the national apprenticeship system

sponsors of programs - employers, unions, community colleges - have to register

with a state or federal apprenticeship agency that, in turn, determines whether

their programs meet a set of regulatory requirements on things like program

length, balance of on-the-job training versus classroom instruction, and the

apprentices’ wages and working conditions.

IRAP REGULATIONS & UNION APPRENTICESHIPS

Under the Trump administration’s proposal, programs could seek formal recognition from the Labor Department through a new system of “program accreditation.”

To accomplish this, the Labor Department is planning

to recognize more than 70 individual IRAP “accreditors” and grant them

authority to determine if a program meets a set of high-quality apprenticeship

standards that the department spelled out earlier this year.

NABTU, an umbrella group within the AFL-CIO that represents

15 individual building trade unions, has supported the Trump administration,

but that would all change if builders, mainly non-union builders are allowed to

take part in IRAP, a building trade’s official said. At that point, the trade

unions would organize members to accuse the administration of betraying

commitments to blue collar workers, the official said, speaking with Bloomberg

Law on condition of anonymity.

Yet, the administration contends that The National Apprenticeship Act (NAA), 29 U.S.C. 50, authorizes the Secretary of Labor “to bring together employers and labor for the formulation of programs of apprenticeship. The U.S. Department of Labor (the Department or DOL) proposes doing so through a new program recognizing Standards Recognition Entities (SREs) of Industry-Recognized Apprenticeship Programs (Industry Programs).

This

new program is intended to harness industry expertise and leadership to meet

the United States’ skills needs in the twenty-first century.

Opponents of IRAP’s also argue that the proposed quality-assurance process for IRAPs closely resembles the national accreditation system of for-profit career colleges and trade schools.

Unions and other opponents of IRAP's say that IRAP’s will not be properly regulated for quality-assurance by the government, and will enable the rise of multiple accreditors with overlapping jurisdictions and competing standards, and will not provide clear mechanism for holding accreditors or programs accountable for poor outcomes.

In response the DOL proposes that the new IRAP Standard

Recognition Entities (SREs) will be recognized for 5 years. The SRE must

reapply if it seeks continued recognition after that time, using the same

application form it submitted initially. The Department proposes a 5-year time

period to be consistent with best practices in the credentialing industry.

IN CONCLUSION

The President and policymakers working to expand apprenticeships

should also work to eliminate occupational segregation in apprenticeship

programs to ensure that black/African-Americans have access to apprenticeship

programs in the highest-paying occupations.

Policymakers should also ensure that new IRAP regulations include the construction industry, while also ensuring apprenticeship programs

are required to comply and support wage progression policies that help ensure

that the highest-wage programs remain well-paying.

Furthermore, policymakers should seek to expand

apprenticeships into new industries, such as IT, healthcare, and childcare,

while increasing wages across the board.

As our network has reported in the past, the massive corruption that plagues one of the largest industries in the United States, construction, has never been fully remedied, and it is alive and well in 2019. The blood and sweat that has been poured out by black tradesmen and women in the hope of realizing the American dream, has always been undermined by secretive organizations, pacts, and industry gangs.

‘Mexican Cliques in Construction’, a book by thirty-year Hispanic carpenter Ricardo Charles, details a story of racism, fraud, discrimination and organized crime that is controlling the construction industry across the state of Texas.

In his interview with reporter Greg Groogan, of Houston’s FOX26, Ricardo Charles was asked if black construction workers were welcome on construction sites in Texas. Charles said, "Oh no, blacks, they are out of the question. Blacks are out of the question. Nobody wants a black person in there." Charles, a US Army Veteran, was speaking about what the "cliques" would say about black tradesmen in the workforce.

Mexican racism plays a major part in keeping out blacks workers. Charles says those who run organized construction “cliques”, largely Hispanic crews almost never willingly hire black construction laborers.

The practice of rejecting black labor is deeply entrenched discrimination which extends to white workers as well, Charles said.

"They have these groups that are going to harass you, they want to insult you, degrade you. They want to make it very, very hard on you. They want to make false accusations about you: that you don't know how to do the job, you don't know how to talk to them, but they are all in the same conspiracy. It is a gang, like organized crime," Charles said.

For years Black tradesmen and women have been targeted by these secretive Mexican labor gangs according to Charles, effectively cutting black workers off from decent-paying construction. According to Ricardo Charles, Mexican groups conspire to keep jobs for themselves in industrial construction, and work with construction contractors to keep black tradesmen and women unemployed.

In an interview with Bob Price, Charles stated,"Corruption has been going on inside the plants for many years, but today's workforce comes with a culture of bribes. The Mexican culture of bribery makes it hard for ordinary citizens to be part of the workforce. However, these cliques help the employers by controlling the job sites by driving out 'unwanted' new workers. Anybody who disagrees with an unlawful act gets terminated."

"The traditional way of hiring through human resources has changed. Corrupt supervisors and managers inside do the hiring and firing giving preference to relatives and friends who, on occasion, pay to obtain the job. The employee of choice is the one who can be manipulated and does not report criminal acts. Eventually these type of workers join the existing group adding more crime into the system." Charles continued.

This evasive form of discrimination and nepotism being practiced throughout the industry is causing thousands of talented black construction workers to become bitter and discouraged. Recently in Atlanta black tradesmen confronted a Mexican construction worker who hung a noose on the job site. The noose incident in Atalanta and other cities, is provoking racial tensions that already exist, and these types of situations could have very ugly outcomes.

Since many millions of Mexican workers do not speak the official language, they commit fraud by cheating on the NCCER certifications and safety exams. Charles says they are supported by employers with no rights for the ordinary worker; they are organized criminals, and terrorist.

Over dozens of years and hundreds of sites across Texas, including the giant petrochemical complex in Port Arthur, he says Mexican construction cliques have muscled honest workers out of millions of dollars.

Money that's made gang bosses rich. He's talking about bribes. They call it "Mordida" in Mexico, the bite.

"This is actually just like in Mexico. It's not how much you know, it's who you know," Charles said. "Everybody knows. Yes, many people know that you have to belong to a clique in order to work. Mexicans exploiting Mexicans and contractors looking the other way," he said.

There's nothing casual about his allegations. Everything he's witnessed:

-- The "pay for play"

-- The graft

-- The enforced silence

-- And the corrupt complicity of contractors

He has also brought his allegations and evidence to the FBI.

It’s all recorded in his book “Mexican Cliques in Construction,” Twelve chapters including the author's background with more than thirty years experience in construction in 244 pages. Copies of "Mexican Cliques in Construction" can be obtained by contacting Ricardo Charles through his email address: ricardocharles46@hotmail.com.

Black tradesmen and women must Organize! Organize! Organize! And recognize what how deep the bribery and discrimination in the construction industry runs, and how they are being targeted. Black construction tradesmen and women in the United States descend from a linage of master tradesmen and craft-workers, and only by organizing their labor and talents together as a single force will they ever realize true success & potential in this industry that has a notorious history of racial discrimination.

Join our site today and network with black construction professionals from all trades across the United States!

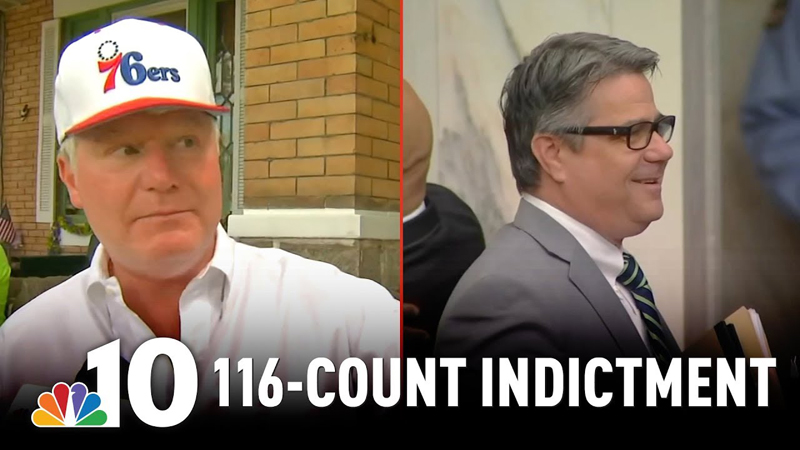

One year ago a lawyer by the name of Michael Coard wrote a

seven part series for the Philadelphia Tribune exposing the blatant racist

practices of the construction industry in the Philly metropolitan area, and how

the city council was being“pimped” by the labor unions.

In his brilliant article titled, ‘Is Council pimped out to racist labor unions?’ Coard exposed now federally indicted, John “Johnny Doc”

Dougherty, Business Manager of Philadelphia Building and Construction Trades

Council (PBCTC) as well as of Local 98 of the International Brotherhood of

Electrical Workers (IBEW).

Attorney Michael Coard (photo above), who serves as an Adjunct Professor

at Temple University, and according to his Twitter profile is an, “African,

Attorney, Radio & TV Host, University Professor, Newspaper Columnist, and

Magazine Journalist- but mostly just The Angriest Black Man in America,” exposed

how in 2016 “Johnny Doc” and his PBCTC, a group of “white suburbanite men” were

responsible for nearly 65 percent of small, city-funded construction projects,

while having absolutely no Blacks whatsoever on the workforce in a city with a

Black population approaching nearly 50 percent.

And According to Coard, “as of 2013, when the most reliable

figures are available, about 80 percent of PBCTC carpenters, electricians,

painters, etc. were white.”

“Although I’m not (yet) saying he, personally, is a racist,

I am unequivocally saying his policies are blatantly racist and the unions he

controls are blatantly racist because I do have incontrovertible evidence of

that. And it’s the direct result of what we lawyers call “disparate impact.” In

other words, while it’s relatively difficult to prove what’s in a person’s

head, it’s easy to prove the effect- or impact- of what’s in his/her head. That

is done by simply looking. And what I see in Dougherty’s policies and unions

are racially ugly,” Michael Coard said in his Tribune article.

According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, John “Johnny Doc” Dougherty

spent 25 years controlling some of the biggest chess pieces in Philadelphia,

building Local 98 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW)

into a political powerhouse that helped to elect mayors, council members, and

members of the state Supreme Court, including his brother, Justice Kevin

Dougherty. He’s been credited with playing an integral role in the ongoing

redevelopment of the city’s Market East corridor.

In his heavy hitting article Coard asserts, “Let’s get back

to Dougherty. In fact, let’s get back to him and Council jointly. In order to

get the answer to my inquiry, i.e., “Is Council Pimped Out To Racist Labor

Unions?,” I asked him these three questions:

1. What is the percentage of Black workers in IBEW Local 98

and also in each of the other 30 Philadelphia-area building trades unions

(alphabetically) from Boilermakers Local 13 through Teamsters Local 312?

2. What exactly have you done within the past ten years to

increase the percentage of Black workers in the local building trades unions?

3. Since 2008 through 2018, how much money have you, your

labor union, and all PACs financially connected with you and also with your

labor union contributed to each current Council member for election as well as

reelection?”

But now “Johnny Doc” faces a 116-count indictment from the

U.S. Attorney’s office, the indictment which alleges embezzlement and conspiracy

has many white Philadelphia tradesmen wondering can the their control of the

council survive without its kingmaker, the political figure who amassed so much

power behind the scenes, that he was more influential than the mayor.

According to the Inquirer,” Dougherty grew so powerful that

he was soon able to pressure a conglomerate like Comcast, during private hotel

meetings, to steer nearly $2 million worth of work to his old friend’s

electrical company.”

And in 2015 “Johnny Doc” showed just how strong his

political power and influence with working class voters had become when he correctly

predicted that most of the city’s labor unions would unite around a single

mayoral candidate, and they eventually did, electing Jim Kenney as Mayor of Philadelphia.

But, Mayor Jim Kenney, according to Coard, “who, is a white

man; has taken a strong stand against racial discrimination in the construction

industry has taken than the lead in calling for nearly 30 percent of all ‘Rebuild’

workforce hours to go to Black (as opposed to merely “minority”) workers.“

The Mayor’s Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) also “conducts

Annual Disparity Studies to track the progress of Blacks and other “minorities”

on major construction projects, which Coard hoped would "expose the outrageous racist

disparities we all suspected,” according to Coard.

Yet, government lawyers have alleged among other charges

that, City Councilman Henon, a union electrician elected in 2011 on a wave of

Local 98 money, is a corrupt politician who sold his Council seat in exchange

for a $73,000-a-year, do-nothing job. Prosecutors allege he then served as

Dougherty’s puppet, backing votes and advancing government actions that

benefited the labor leader’s personal and professional interests.

On March 21, “Johnny Doc” Dougherty urged a judge to dismiss

all charges that he corruptly bought Philadelphia City Councilman Bobby Henon’s

vote on key issues, calling the allegations a “feeble attempt at criminalizing

the legislative process.”

What U.S. District Judge Jeffrey L. Schmehl will make of "Johnny Doc's" assertions remains to be seen. No hearing had been scheduled to consider

the defense motion as of Thursday, and prosecutors had not yet responded to it

in court.

In recent years of Philly corruption, the city has seen its Congressman

Chaka Fattah, the representative from the 2nd congressional

district, indicted and found guilty on racketeering charges. The Federal government

found Chaka guilty of siphoning money from an education nonprofit to repay an

illegal campaign loan, and sentenced him to 10 years in federal prison.

Tradesmen and the general public have been extremely

interested in Tesla’s upcoming pickup truck ever since images of the truck were

released at the launch of the Model Y a few years ago. During a recent podcast

interview, Tesla CEO Elon Musk has made new statements regarding the pickup

truck, including saying that he aims to keep the truck under $50,000.

“We don’t want it to be really expensive. I think it got to

start at less than $50,000 – it’s got to be like $49,000 starting price max.

Ideally less. It just can’t be unaffordable. It’s got to be something that’s

affordable. There will be versions of the truck that will be more expensive,

but you’ve got to be able to get a really great truck for $49,000 or less,”

Elon said in an interview.

The pickup truck which is still under development has options

planned such as 400-500 miles of range on a single charge, dual Motor

All-wheel-drive powertrain with dynamic suspension, as well as ‘300,000 lbs of

towing capacity’.

That’s right, 300,000 lbs of towing capacity! Ford’s F150

has a max towing capacity of 13,200 lbs.

The design, which has still not been confirmed, will sport a ‘Blade runner-like’ design, and might be unveiled this summer according to the Tesla CEO.

Musk thinks that some people will think that “it doesn’t

look like a truck.” Musk compared the new trucks design to the transition

between the horse and carriage and the automobile.

Ford, which produces the F150, the best-selling pickups in

the US for decades and won Motor Trend’s 2018 “Truck of the Year” award. Undoubtedly

Tesla’s biggest competitor in pickup truck industry, Ford has invested $500

million in the electric truck startup Rivian, and has recently released a statement

confirming that they have plans to electrify the F150.

And although the 2019 F150 comes in at the low base price of

$28,000, it sucks up gasoline like a vacuum, and the upcoming Tesla pickup is

All-electric. Musk also feels Tesla’s new pickup “will be a better truck than

an F150 in terms of truck-like functionality, and be a better sports car than a

standard [Porsche] 911.

At the base price of $49,000, the Tesla pickup would also be

significantly less expensive than the $69,000 base price for the Rivian pickup

truck set to be released in 2020.

This ambitious project for Tesla and Musk, as well as for Rivian

and Ford is changing the pickup truck industry and may change the world in

terms of productivity from individuals using these All-electric trucks such as

tradesmen and truck lovers in general.

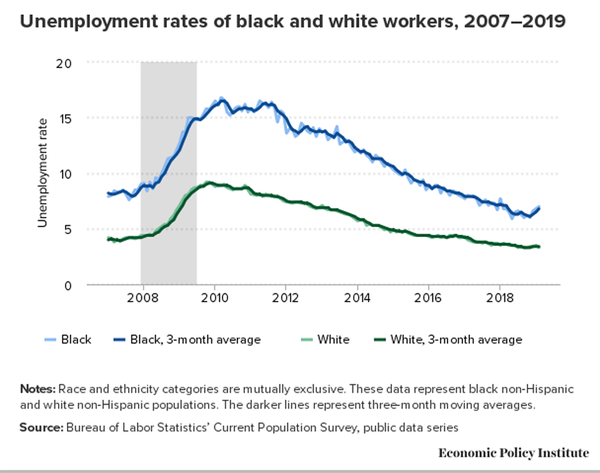

Regardless of whether the black unemployment rate goes up or

down in a given month or year, president Trump celebrates it as the “lowest in

history.”

The idea that black unemployment was at its

lowest point on record since 1972, when the rate declined to 5.9% May 2018, was

completely erased when black unemployment rates shot back up to nearly 7% in February

of 2019.

In fact, according to history black

unemployment was lower in 1969, and some reports show it was lower in the

1950s.

Yet president Trump continues to talk about it as the lowest

rate in history. Why?

F.Y.I. The unemployment rate is based on the number of unemployment

claims made with the state. Most of those who are unemployed long term, work

part time, are a contractor, or have a job in Obama’s ‘gig economy’ like as an Uber or Lyft driver,

aren't eligible for unemployment benefits.

In other words, potential workers no longer eligible to file

unemployment claims, as well as people who weren't laid off from the right kind

of full-time job, are not included in federal unemployment figures; the one’s

Trump brags about.

PART 1: THE EMPLOYMENT GAP

BETWEEN BLACK & WHITE WORKERS

For the last 40 years, the black unemployment rate has been

about double the white unemployment rate, and, instead of

focusing on solutions to close this constant, and historic gap between black

& white workers, president Trump, and other politicians, instead blindly

celebrate the black unemployment rate, which is actually higher than any other

race reported in the United States.

Moreover, even at an annual rate of 6.6%, the black unemployment rate is still consistently more than double the white unemployment rate of 3.2% in 2018. In fact, the last time the white unemployment rate was 6.6% was in 2012, when the black unemployment rate was at a staggering 14%.

If white unemployment levels were anywhere near this high, it would be considered a national crisis.

The black unemployment rate peaked at 16.8 percent in March

2010, and during that year, unemployment rates for black men specifically

in some major U.S. cities, such as Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, peaked higher then 30%,an unimaginable reality for any person of working age.

According to the’ Council of Economic Advisers’ (CEA) “there has historically been a wide gap in employment rates between black and white prime-age adults” and that “it currently appears to be driven primarily by the employment disparity for males across the two races, rather than females.”

Economists also point to systemic biases in hiring and

firing that puts black workers at a disadvantage, this gap in employment is due in much

part to “labor market discrimination,” the “first fired, last hired” phenomenon,

and “the lasting effects of higher incarceration rates among black males.”

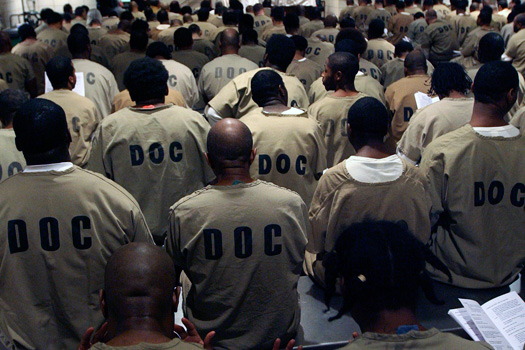

PART 2: WORKING AGE BLACK MEN WORKING FOR THE STATE, IN PRISON.

Now, when discussing black men of working age (15-53 years old), we

must take note of the black American prison populations, that is currently at

487,300. Black Americans account for 12% of the U.S. adult population, yet

blacks make up 33% of America’s federal and state prison inmates, which is more

than twice their share of the U.S. population.

In contrast, whites accounted for 64% of adults in the U.S.

but 30% of prisoners, according to the Pew Research Center.

Incarcerated people are not counted in unemployment figures.

If they were to be, the unemployed numbers would jump, particularly for blacks,

say many economists. This lack of working age black men in the job market is

destroying black families and communities nationwide.

PART 3: THE WEALTH GAP

THAT KEEPS BLACK WORKERS DOWN.

The jobs that black workers and white workers get do not pay

the same, and all data shows that black workers earn less money and build less

wealth than white workers. The typical full-time black worker still earns about

$12,000 less annually than a white worker.

In addition to wages, wealth disparities between black and

white workers are even more disturbing. In 2016, the median wealth of white

Americans was $142,180 compared to $13,460 for black Americans. Currently, the

median black household has about 10 percent of the wealth of the median white

household.

Wealth, which is calculated by combining a person’s home value, savings, and investments, is a cushion that helps families keep themselves afloat during periods of unemployment. And during the 2007 mortgage crisis Black home ownership took a major hit. Today blacks own approx. 32% less homes as compared to white households. Even when black Americans do become homeowners, if the neighborhood they reside is more than 50% black, their homes are valued at nearly half the price of similar homes in mostly white communities.

PART 4: THE REALITY OF THE

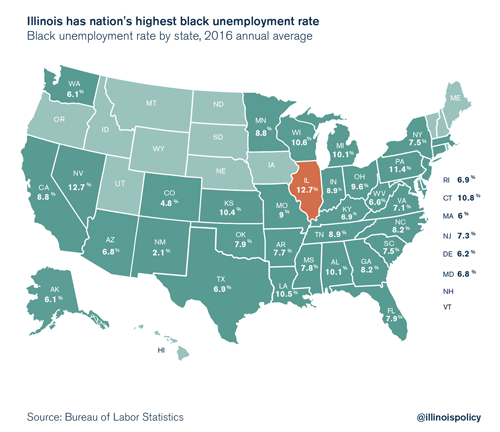

NUMBERS STATE BY STATE, CHECK OUT ILLINOIS.

Although president Trump celebrates low unemployment numbers

for blacks, and at every chance spews out the statistics that he has brought

down black unemployment. The White House has not directly addressed the employment

and wage gaps between black and white workers any manner. Nor has the previous

administrations of Barrack Obama, Bush 1&2, Clinton, or any of the other

administrations over the past 40+ years.

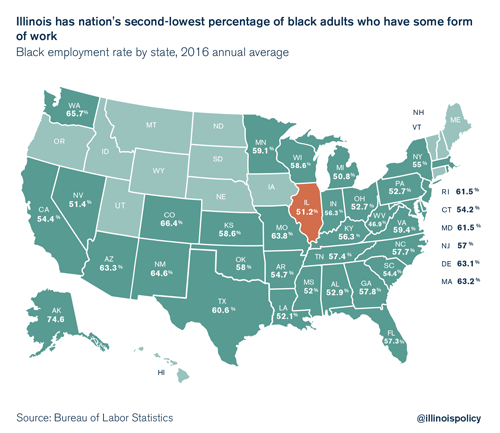

In fact, when further examining black unemployment numbers across the United States we find several states such as Illinois and Nevada that have the highest black unemployment rates in the U.S. according to annual unemployment data released by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Illinois’ 12.7 percent black jobless rate is the highest in the U.S., tied with Nevada. However, Illinois’ black population is seven times as large as Nevada’s, meaning Illinois’ crisis is playing out on a much larger scale.

The number of black people working in Illinois has been in

decline since the year 2000. There were 77,000 fewer blacks working in Illinois

in 2016 compared with 2000, a shocking 10% decline in total employment. By

comparison, white & Hispanic employment in Illinois is actually up by

272,000 since 2000, according to the BLS.

Several other U.S. states show that under 60% of black workers between the ages 35-53 are employed:

West Virginia - 46.9%

Michigan - 50.8%

Illinois - 51.2%

Nevada - 51.4%

Mississippi - 52%

Louisiana - 52.1%

Alabama - 52.9%

Pennsylvania - 52.7%

Ohio - 52.7%

Connecticut - 54,2%

South Carolina - 54.4%

California - 54.4%

New York - 55%

Kentucky - 56.3%

Indiana - 56.3%

Florida - 57.3%

Tennessee - 57.4%

North Carolina - 57.7%

Georgia - 57.8%

Oklahoma - 58%

Wisconsin - 58.6%

Kansas - 58.6%

Montana - 59.1%

Virginia - 59.4%

THESE NUMBERS OF BLACK EMPLOYMENT IN SEVERAL STATES IS AT CRISIS LEVELS, yet many state Assemblies and governors have largely ignored these statistics.

BLACK WORKERS DESERVE MORE, THEY DESERVE BETTER!

Even as the U.S. economy continues to grow, black workers still see their wages stagnant, their working age men locked in cages and unable to earn a living wage for their families, and black home ownership considerably lower than white workers, and Hispanic workers.It will take more than a couple of years of Trump’s economy to close the nations historic racial wage gaps, and compensate for years of lower incomes, and lower wealth for black workers.

“We should never celebrate the fact that black folks are

just working,” said Andre M. Perry, an expert at the Brookings Institute, told

the Washington Post in an interview. “It’s like saying: ‘Look, you have a job.

Why should you complain?’ And I think that’s what Trump is signaling. He’s

saying to the black community, 'Look what I’ve given you,’ and not necessarily

saying, ‘Let’s look at the percentage of people in poverty, let’s look at the

percentage of people rising to the middle class.'

“Are black folks getting the kinds of jobs that are

propelling them to the middle class? No, they are not,” says Perry. “You still

see that gap in the unemployment rate, and you still see that gap in median

income.”

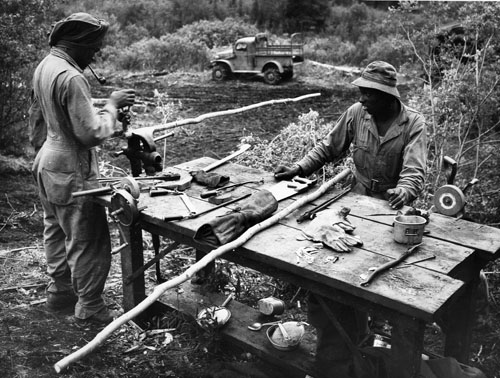

The attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941,

would bring the United States into World War II, but it also raised a concern

that the U.S. Territory of Alaska was vulnerable to Japanese attack. The Aleutian

Islands off southwest Alaska were closer to Japan than any point in North

America. In the event of a Japanese invasion, the Alaska-Canada highway (ALCAN) would be

necessary to protect Alaska civilians.

Overland travel by car, truck, or train between the United

States and the Alaskan territory at that time was just not possible due to the

rugged topography, and Canada did not have an incentive to build a connecting

road through its territory north of Dawson Creek.

So, in 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt along with the

Canadian government authorized the construction of the Alaska-Canada Highway

(ALCAN) to connect Alaska to the continental United States.

Construction of the highway begin on March 8, 1942, but, in order

for this highway to prove effective, the speed in which it was constructed was

essential to the military’s needs; the Alaska-Canada Highway needed to be built

in 8 months’ time.

To complete this grueling highway in just 8 months, the U.S.

government hired private contractors and also commissioned the Army Corps of

Engineers. Due to World War II, many members of the Army Corps of Engineers

were in the South Pacific assisting with war efforts. This led to the need for

more manpower to complete the administration’s ambitious Alaska Highway

project. As a result, the War Department led by Colonel William M. Hoge, took

the historic step of deploying Black/African-American regiments of the Army Corps of

Engineers.

Approximately

5,000-7,000 of the initial 11,000 troops assembled to complete the highway and

install the companion Canol pipeline were Black. There were four regiments of

African-American engineers involved in building the Alaska-Canada Highway, the

93rd Engineer General Service Regiments, the 95th Engineer General

Service Regiments, the 97th Engineer General Service Regiment and the 388th

Engineer Battalion. Theirs were the first black regiments deployed outside the

lower 48 states during the war.

In the interest of speed, officials decided to build the

road in two phases. A pioneer road would be carved out of the difficult terrain

in 1942 to open the route for supply trucks by year's end. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was to build

the pioneer road, with Army engineering units and private contractors. Initially, the Army divided the 1,500-mile project into

five segments, with private contractors responsible for the portion from Whitehorse

to Big Delta, about 560 miles. But after proving to be a very difficult feat to

complete, the contractors work was extended by 100 miles to the east.

Since approval of the Selective Service Act of 1940, Black

American soldiers had been drafted into the Army on the same terms as whites,

but as Heath Twichell explained in his book on the Alaska Highway,

"Segregation's legacy of bigotry and prejudice severely limited the

possibilities" for the work they would do:

“As a result, relatively few black infantry, armor, or artillery

units were organized during World War II… In the end, black soldiers were assigned to

more than their share of units engaged in low-tech, high-sweat duties in the

Engineers and Quartermaster Corps. Although the Corps of Engineers put most of

its new black soldiers into general-purpose construction battalions and regiments,

shortages of heavy equipment sometimes resulted in the black units' being

issued fewer bulldozers and more shovels and wheelbarrows than the white units

got.”

Another touchy issue was where to station the new black

units. In the United States, military leaders felt they had to worry about the

impact of large numbers of young black soldiers on nearby civilian communities.”

[Northwest , p. 97-98]

The enlisted men, most of them from the South, faced racial

discrimination from white officers. The black soldiers were barred from

entering any towns for fears from white soldiers that they would procreate a “mongrel”

race with local women.

During the construction of the highway, the black American

soldiers endured winter conditions they had never experienced before, including

record low temperatures, the temperatures ranged from 90 degrees above zero in

summer to 70 degrees below zero during the winter. The black troops also had to fight swamps,

rivers, ice and cold, whiles battling the segregation with in their own corp.

Jim Sutton, a white American soldier who had worked on the highway project

alongside the blacks stated:

"They were up here when we got up here. We were put in barracks, wooden barracks, and we had stoves and everything. These poor black people were doing the same job as we were and they had them in tents. I didn't think that was really fair."

Housing wasn’t the only form of injustice the black soldiers

faced, but many times struggling through long difficult trips to reach the project

site with their equipment, the black American troops found that their best equipment

would be shifted to the white units.

Although, in practice the African-Americans were involved in many phases of construction, often never working with the white troops, but performed the more grueling labor intense work, while white troops sometimes less skilled, managed and directed. For this reason, many of the soldiers felt they were fighting two wars, one against the Axis (Japan, Germany and Italy) and a second against segregation.

After cutting an access road over Mentasta Pass from Slana

to Tok, the all black 97th Engineers battalion was used to perform the grueling work of speeding

the opening of the northernmost third of the Alaska Highway by helping the

private contractors and the 18th Engineers close the gap between Whitehorse and

Big Delta. Similarly, after opening a trail from Carcross to help the 340th

Engineers reach Teslin, another all black battalion of the 93rd Engineers

would start work on the pioneer road from that point toward Whitehorse, during

freezing conditions.

With private contractors and Army engineering units working on segments of the Alaska Highway, gaps began to close in August. By the end of September, only the most difficult sections, through eastern Alaska and the southwest corner of the Yukon, remained to be completed. [North to Alaska , p. 130]

The final gap was closed on October 29, 1942, south of Kluane Lake. Coates quoted Malcolm MacDonald, British high commissioner to Canada, on the final moments:

The final meeting between men working from the south and men working from the north was dramatic. They met head on in the forest. Corporal Refines Sims, Jr., a negro from Philadelphia [of the 97th Engineers] . . . was driving south with a bulldozer when he saw trees starting to topple over on him. Slamming his big vehicle into reverse he backed out just as another bulldozer driven by private Alfred Jalufka of Kennedy, Texas, broke through the underbrush. Jalufka had been forcing his bulldozer through the bush with such speed that his face was bloody from scratches of overhanging branches and limbs. That historic meeting between a negro corporal and white private on their respective bulldozers occurred 20 miles east of the Alaska-Yukon Boundary at a place called Beaver Creek. [North to Alaska , p, 130-131]

One of the greatest accomplishment of the black troops was Sikanni

Chief River Bridge. The Sikanni Chief River is a fast-moving river that is over

300 feet wide located about 162 miles outside of Dawson Creek, Canada. The

African-American engineers built the bridge without heavy equipment, utilizing

minimal supplies and in miserable conditions. They used hand tools, saws, and

axes to build the bridge in less than three days using lumber from nearby

trees.

During some phases of the bridges construction the black

troops had to plunge chest deep into the river’s freezing and rapidly moving

waters to set trestles. The soldiers used the headlights of trucks to keep

working at night while singing work chants and chain gang songs. Despite the

military still being segregated, after witnessing this amazing feat, Col. Heath Twichell Sr. ordered his white

officers to eat with the black enlisted men.

Over the years, as public attitudes changed, the

African-Americans who helped build the pioneer trail received recognition for

their accomplishment. Brinkley interviewed some of the veterans:

“They all talked to me about duty for country and reminisced about their harsh living conditions, tasteless food, and bitter winters where frostbite was their primary foe. Stories about wading chest deep into freezing lakes to erect bridge trestles or having a finger fall off when the temperature hit a record -70o F or lowering the coffin of a comrade into the cold ground conjured bleak memories of Jack London's most brutal tales like "To Build a Fire" or "Burning Sun." Snowdrifts were often twenty feet deep. "For months on end, I couldn't get a real night's sleep," one veteran recalled. "I had nightmares I was freezing to death." Although these black soldiers had at their disposal 11,107 pieces of equipment, trucks, tractors, crushers, graders, and bulldozers, breakdowns occurred hourly. The job was daunting. Never before, it seems, had so many survey sticks been hammered into the earth at a given time. To keep morale up they often chanted old southern work tunes like "Steel-Driving Song" and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot." With brawn and courage and valor they persevered, completing the Alcan Highway in just over eight months, with the official opening on 21 November 1942. [Alcan , p. 10]

The African-American regiments that built the Alaska-Canada

Highway established a reputation for excellence especially in the field of

bridge building. However, their accomplishments were consistently ignored by

mainstream media and press. It took decades for them to receive proper

recognition for their achievements. Some say they were as “legendary” as the

Tuskegee Airmen and the Buffalo Soldiers.

Many people attribute the success of these African-American

engineers during the Alaska-Canada Highway project as one of the events that

led to eventual desegregation of the military in 1948. Some call the ALCAN

Highway the “Road to Civil Rights” for this reason.

After just over 8 months , the Alaska-Canada Highway (ALCAN)

was completed on November 21, 1942. The ALCAN highway project is still

considered one of the biggest and most difficult construction projects ever

completed by the US Army Corps of Engineers. It stretches 1,422 miles from

Dawson Creek, British Columbia in Canada to Big Delta, Alaska. The project cost

about $138 million dollars and was the most expensive World War II construction

project.

Approximately 30 men died during the Alaska-Canada Highway construction project. In 1992 there were over 2,000 different celebrations held to commemorate the highway's 50th anniversary, but none of them honored, and most hardly mentioned, the black units who represented one of the projects largest portions of manpower. James Eaton, curator of the Black Archives Research Center and Museum at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee, called the soldiers, "A lost page in history."

On July 4, 1992, the city of Anchorage, Alaska invited several of the veteran black troops from the corp. of engineers to participate in the city's parade down Main Street. Two of them, Albert E. France andDonald W. Nolan, Sr., were from Baltimore. France was a 75-year old retired railroad worker, while Nolan was a 72-year old retired postal worker, both recalled in a newspaper interview, the first thing they remembered from working on the Alaska-Canada Highway was the cold:

"It was awful

cold and it snowed for days," recalled Mr.France . . . . It was the

coldest winder on record in the territory.

"Leather would freeze," recalled Mr. Nolan . . . .

"We'd take galoshes, rubber galoshes - we called them 'Arctics' - and we'd

wear three, four pairs of socks we would double up on pants. We slept on the round

in pup tents."

“Food was never plentiful. C-rations, bittersweet chocolate

and "hardcracks" might be all a soldier would get to eat after the

harsh climate cut off supply routes.”

"We'd kill a bear, a huge black bear," said Mr.

Nolan,"about 9, 10 feet high, and those chops were delicious."

When the snow stopped, the rains started and the rivers swelled.

In summer, mosquitoes droned like airplanes and the "muskeg," a

uniquely Alaskan bog, swallowed tractors… In that barren landscape, the

off-work hours could seem exceptionally long.

Looking back, Nolan said he was glad to have served on the project. "You have something to tell your kids." [The Baltimore Sun , July 4, 1992]

Memorials for the black soldiers that helped in the competition

of the ALCAN Highway are scattered along

the highways 1,400 miles path. One of the most recognized memorials is the‘Black

Veterans Memorial Bridge’ which was dedicated in 1993 to the African-American

engineers who died during the construction project.

Congress in 2005 said that the wartime service of the four

regiments covered here contributed to the eventual desegregation of the Armed

Forces.

After four decades of operation, the largest black-owned construction company in the United States, THOR Construction companies, a Minneapolis-based contracting and management firm is shutting down, according to its founder & chairman, Richard Copeland.

After experiencing explosive growth over the last 2 years, THOR construction company will be ending operations. THOR in 2017 had revenues of $368 million, up 162% from $140 million in 2016. According to THOR, just under $197 million came from the acquisition of JIT Energy Services, a minority-owned energy management and utility cost reduction services firm, for an undisclosed amount.

This year, THOR Companies reportedly begin to revamp its

business model in an attempt to overcome some financial challenges. In this

effort, THOR hired Manchester Cos. as its chief reorganization officer, as it

worked to salvage its financial affair. Manchester, which is also based in

Minneapolis, is known for turning around and restructuring companies.

However, in January of 2019, Sunrise Banks sued THOR and its

founder and chairman Richard Copeland, pursuing restitution exceeding $3

million. The bank requested that a receiver be appointed to take control of