Ray's article

The attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941,

would bring the United States into World War II, but it also raised a concern

that the U.S. Territory of Alaska was vulnerable to Japanese attack. The Aleutian

Islands off southwest Alaska were closer to Japan than any point in North

America. In the event of a Japanese invasion, the Alaska-Canada highway (ALCAN) would be

necessary to protect Alaska civilians.

Overland travel by car, truck, or train between the United

States and the Alaskan territory at that time was just not possible due to the

rugged topography, and Canada did not have an incentive to build a connecting

road through its territory north of Dawson Creek.

So, in 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt along with the

Canadian government authorized the construction of the Alaska-Canada Highway

(ALCAN) to connect Alaska to the continental United States.

Construction of the highway begin on March 8, 1942, but, in order

for this highway to prove effective, the speed in which it was constructed was

essential to the military’s needs; the Alaska-Canada Highway needed to be built

in 8 months’ time.

To complete this grueling highway in just 8 months, the U.S.

government hired private contractors and also commissioned the Army Corps of

Engineers. Due to World War II, many members of the Army Corps of Engineers

were in the South Pacific assisting with war efforts. This led to the need for

more manpower to complete the administration’s ambitious Alaska Highway

project. As a result, the War Department led by Colonel William M. Hoge, took

the historic step of deploying Black/African-American regiments of the Army Corps of

Engineers.

Approximately

5,000-7,000 of the initial 11,000 troops assembled to complete the highway and

install the companion Canol pipeline were Black. There were four regiments of

African-American engineers involved in building the Alaska-Canada Highway, the

93rd Engineer General Service Regiments, the 95th Engineer General

Service Regiments, the 97th Engineer General Service Regiment and the 388th

Engineer Battalion. Theirs were the first black regiments deployed outside the

lower 48 states during the war.

In the interest of speed, officials decided to build the

road in two phases. A pioneer road would be carved out of the difficult terrain

in 1942 to open the route for supply trucks by year's end. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was to build

the pioneer road, with Army engineering units and private contractors. Initially, the Army divided the 1,500-mile project into

five segments, with private contractors responsible for the portion from Whitehorse

to Big Delta, about 560 miles. But after proving to be a very difficult feat to

complete, the contractors work was extended by 100 miles to the east.

Since approval of the Selective Service Act of 1940, Black

American soldiers had been drafted into the Army on the same terms as whites,

but as Heath Twichell explained in his book on the Alaska Highway,

"Segregation's legacy of bigotry and prejudice severely limited the

possibilities" for the work they would do:

“As a result, relatively few black infantry, armor, or artillery

units were organized during World War II… In the end, black soldiers were assigned to

more than their share of units engaged in low-tech, high-sweat duties in the

Engineers and Quartermaster Corps. Although the Corps of Engineers put most of

its new black soldiers into general-purpose construction battalions and regiments,

shortages of heavy equipment sometimes resulted in the black units' being

issued fewer bulldozers and more shovels and wheelbarrows than the white units

got.”

Another touchy issue was where to station the new black

units. In the United States, military leaders felt they had to worry about the

impact of large numbers of young black soldiers on nearby civilian communities.”

[Northwest , p. 97-98]

The enlisted men, most of them from the South, faced racial

discrimination from white officers. The black soldiers were barred from

entering any towns for fears from white soldiers that they would procreate a “mongrel”

race with local women.

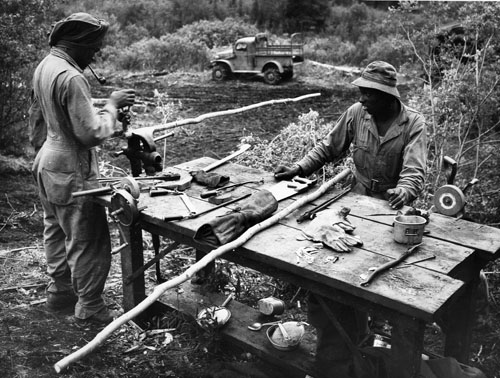

During the construction of the highway, the black American

soldiers endured winter conditions they had never experienced before, including

record low temperatures, the temperatures ranged from 90 degrees above zero in

summer to 70 degrees below zero during the winter. The black troops also had to fight swamps,

rivers, ice and cold, whiles battling the segregation with in their own corp.

Jim Sutton, a white American soldier who had worked on the highway project

alongside the blacks stated:

"They were up here when we got up here. We were put in barracks, wooden barracks, and we had stoves and everything. These poor black people were doing the same job as we were and they had them in tents. I didn't think that was really fair."

Housing wasn’t the only form of injustice the black soldiers

faced, but many times struggling through long difficult trips to reach the project

site with their equipment, the black American troops found that their best equipment

would be shifted to the white units.

Although, in practice the African-Americans were involved in many phases of construction, often never working with the white troops, but performed the more grueling labor intense work, while white troops sometimes less skilled, managed and directed. For this reason, many of the soldiers felt they were fighting two wars, one against the Axis (Japan, Germany and Italy) and a second against segregation.

After cutting an access road over Mentasta Pass from Slana

to Tok, the all black 97th Engineers battalion was used to perform the grueling work of speeding

the opening of the northernmost third of the Alaska Highway by helping the

private contractors and the 18th Engineers close the gap between Whitehorse and

Big Delta. Similarly, after opening a trail from Carcross to help the 340th

Engineers reach Teslin, another all black battalion of the 93rd Engineers

would start work on the pioneer road from that point toward Whitehorse, during

freezing conditions.

With private contractors and Army engineering units working on segments of the Alaska Highway, gaps began to close in August. By the end of September, only the most difficult sections, through eastern Alaska and the southwest corner of the Yukon, remained to be completed. [North to Alaska , p. 130]

The final gap was closed on October 29, 1942, south of Kluane Lake. Coates quoted Malcolm MacDonald, British high commissioner to Canada, on the final moments:

The final meeting between men working from the south and men working from the north was dramatic. They met head on in the forest. Corporal Refines Sims, Jr., a negro from Philadelphia [of the 97th Engineers] . . . was driving south with a bulldozer when he saw trees starting to topple over on him. Slamming his big vehicle into reverse he backed out just as another bulldozer driven by private Alfred Jalufka of Kennedy, Texas, broke through the underbrush. Jalufka had been forcing his bulldozer through the bush with such speed that his face was bloody from scratches of overhanging branches and limbs. That historic meeting between a negro corporal and white private on their respective bulldozers occurred 20 miles east of the Alaska-Yukon Boundary at a place called Beaver Creek. [North to Alaska , p, 130-131]

One of the greatest accomplishment of the black troops was Sikanni

Chief River Bridge. The Sikanni Chief River is a fast-moving river that is over

300 feet wide located about 162 miles outside of Dawson Creek, Canada. The

African-American engineers built the bridge without heavy equipment, utilizing

minimal supplies and in miserable conditions. They used hand tools, saws, and

axes to build the bridge in less than three days using lumber from nearby

trees.

During some phases of the bridges construction the black

troops had to plunge chest deep into the river’s freezing and rapidly moving

waters to set trestles. The soldiers used the headlights of trucks to keep

working at night while singing work chants and chain gang songs. Despite the

military still being segregated, after witnessing this amazing feat, Col. Heath Twichell Sr. ordered his white

officers to eat with the black enlisted men.

Over the years, as public attitudes changed, the

African-Americans who helped build the pioneer trail received recognition for

their accomplishment. Brinkley interviewed some of the veterans:

“They all talked to me about duty for country and reminisced about their harsh living conditions, tasteless food, and bitter winters where frostbite was their primary foe. Stories about wading chest deep into freezing lakes to erect bridge trestles or having a finger fall off when the temperature hit a record -70o F or lowering the coffin of a comrade into the cold ground conjured bleak memories of Jack London's most brutal tales like "To Build a Fire" or "Burning Sun." Snowdrifts were often twenty feet deep. "For months on end, I couldn't get a real night's sleep," one veteran recalled. "I had nightmares I was freezing to death." Although these black soldiers had at their disposal 11,107 pieces of equipment, trucks, tractors, crushers, graders, and bulldozers, breakdowns occurred hourly. The job was daunting. Never before, it seems, had so many survey sticks been hammered into the earth at a given time. To keep morale up they often chanted old southern work tunes like "Steel-Driving Song" and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot." With brawn and courage and valor they persevered, completing the Alcan Highway in just over eight months, with the official opening on 21 November 1942. [Alcan , p. 10]

The African-American regiments that built the Alaska-Canada

Highway established a reputation for excellence especially in the field of

bridge building. However, their accomplishments were consistently ignored by

mainstream media and press. It took decades for them to receive proper

recognition for their achievements. Some say they were as “legendary” as the

Tuskegee Airmen and the Buffalo Soldiers.

Many people attribute the success of these African-American

engineers during the Alaska-Canada Highway project as one of the events that

led to eventual desegregation of the military in 1948. Some call the ALCAN

Highway the “Road to Civil Rights” for this reason.

After just over 8 months , the Alaska-Canada Highway (ALCAN)

was completed on November 21, 1942. The ALCAN highway project is still

considered one of the biggest and most difficult construction projects ever

completed by the US Army Corps of Engineers. It stretches 1,422 miles from

Dawson Creek, British Columbia in Canada to Big Delta, Alaska. The project cost

about $138 million dollars and was the most expensive World War II construction

project.

Approximately 30 men died during the Alaska-Canada Highway construction project. In 1992 there were over 2,000 different celebrations held to commemorate the highway's 50th anniversary, but none of them honored, and most hardly mentioned, the black units who represented one of the projects largest portions of manpower. James Eaton, curator of the Black Archives Research Center and Museum at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee, called the soldiers, "A lost page in history."

On July 4, 1992, the city of Anchorage, Alaska invited several of the veteran black troops from the corp. of engineers to participate in the city's parade down Main Street. Two of them, Albert E. France andDonald W. Nolan, Sr., were from Baltimore. France was a 75-year old retired railroad worker, while Nolan was a 72-year old retired postal worker, both recalled in a newspaper interview, the first thing they remembered from working on the Alaska-Canada Highway was the cold:

"It was awful

cold and it snowed for days," recalled Mr.France . . . . It was the

coldest winder on record in the territory.

"Leather would freeze," recalled Mr. Nolan . . . .

"We'd take galoshes, rubber galoshes - we called them 'Arctics' - and we'd

wear three, four pairs of socks we would double up on pants. We slept on the round

in pup tents."

“Food was never plentiful. C-rations, bittersweet chocolate

and "hardcracks" might be all a soldier would get to eat after the

harsh climate cut off supply routes.”

"We'd kill a bear, a huge black bear," said Mr.

Nolan,"about 9, 10 feet high, and those chops were delicious."

When the snow stopped, the rains started and the rivers swelled.

In summer, mosquitoes droned like airplanes and the "muskeg," a

uniquely Alaskan bog, swallowed tractors… In that barren landscape, the

off-work hours could seem exceptionally long.

Looking back, Nolan said he was glad to have served on the project. "You have something to tell your kids." [The Baltimore Sun , July 4, 1992]

Memorials for the black soldiers that helped in the competition

of the ALCAN Highway are scattered along

the highways 1,400 miles path. One of the most recognized memorials is the‘Black

Veterans Memorial Bridge’ which was dedicated in 1993 to the African-American

engineers who died during the construction project.

Congress in 2005 said that the wartime service of the four

regiments covered here contributed to the eventual desegregation of the Armed

Forces.

After four decades of operation, the largest black-owned construction company in the United States, THOR Construction companies, a Minneapolis-based contracting and management firm is shutting down, according to its founder & chairman, Richard Copeland.

After experiencing explosive growth over the last 2 years, THOR construction company will be ending operations. THOR in 2017 had revenues of $368 million, up 162% from $140 million in 2016. According to THOR, just under $197 million came from the acquisition of JIT Energy Services, a minority-owned energy management and utility cost reduction services firm, for an undisclosed amount.

This year, THOR Companies reportedly begin to revamp its

business model in an attempt to overcome some financial challenges. In this

effort, THOR hired Manchester Cos. as its chief reorganization officer, as it

worked to salvage its financial affair. Manchester, which is also based in

Minneapolis, is known for turning around and restructuring companies.

However, in January of 2019, Sunrise Banks sued THOR and its

founder and chairman Richard Copeland, pursuing restitution exceeding $3

million. The bank requested that a receiver be appointed to take control of

THOR, according to a lawsuit filed in Hennepin District County Court in

Minnesota.

The St. Paul, Minnesota, Sunrise bank claimed that THOR “is

generally not paying its debts as they become due, including payroll

obligations to its employees and its debts to Lender. As a result of this

lawsuit, multiple creditors will likely attempt to engage in a ‘free-for-all

liquidation’ of THOR construction Co.

Although, according to Copeland, “THOR has never missed a

payroll in 40 years to date. We have several companies rallying around this effort;

however, the bank has done everything in its power to put us in receivership.”

In law, receivership is a situation in which an institution

or enterprise is held by a receiver—a person "placed in the custodial

responsibility for the property of others, including tangible and intangible

assets and rights"—especially in cases where a company cannot meet

financial obligations or enters bankruptcy.

In an interview with the Star Tribune in Minneapolis a few

months ago, Copleland said: “We’ve struggled in a tough industry with some of

the best contractors in the world as our competition. We cobbled along for 40

years and never had anything like this happen. We hope to attract new money and

are poised with good customers to do well.”

“We have had a credit line with Sunrise Bank for 11 years.

The LOC [line of credit] was to expire on 12-31-18. The LOC was as high as $5.8

million, but over the last two years, we had reduced the line by $2.8 million

down to $3 million. We also believe that almost half of the $3 million line

remaining, that $1.3 million of it were not legitimate,” Copeland said in an

interview with Black Enterprise magazine.

Yet, as if things couldn’t get worst, in February of this year THOR’s CEO, Ravi Norman (pictured above), stepped down from the company. Norman told the Minnesota publication ‘Finance & Commerce’ that he is no longer an employee at THOR. Norman worked at THOR for several years, serving in CEO and CFO roles at the business.

The closure of THOR construction Co. comes after THOR

celebrated the opening of a new headquarters, a $36 million office/retail

building in north Minneapolis in September of 2018.

THOR Cos. Co was a model contractor admired not only by

other black-owned companies, but by most major contractors for its performance,

and will be greatly missed in the construction industry.

A brief History of

THOR construction Co.

Established in 1980, THOR had previously been involved in

some of the Twin Cities biggest construction projects, such as the U.S. Bank

Stadium and the University of Minnesota’s TCF Bank Stadium, among others. THOR

though most of its business came from work it did out of state.

In early 2017, THOR was selected as a key partner in the redevelopment

of the Upper Harbor Terminal, after the Minneapolis City Council and the

Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board approved, the plans to build hundreds of

units of housing; thousands of square feet for manufacturing, offices, shopping

and restaurants; a public park; and most notably, a performance venue in the

form of a 8,000-10,000 seat outdoor amphitheater.

Over the last 40 years THOR managed to keep its head above

water, while other contractors quickly sank. THOR also was one of the most diverse

construction companies in the industry with an active grassroots recruitment

effort that helped them tap into the black community to hire workers.

Through hard work and dedication THOR Construction evolved

into one of the largest black-owned construction companies in the nation. Along

with their office in Minneapolis, the contractor increased its national

footprint as a full-service self-performing concrete contractor by opening an

office in Las Vegas.

Key THOR self-preforming projects in Las Vegas included

T-Mobile Arena ($375 million), and Mandalay Bay ($66 million).

THOR’s portfolio of self-performing concrete projects also includes

work across a wide spectrum, with a major emphasis on sports facilities and

arenas, along with, hospitality and gaming, mass transit, commercial buildings,

factories, highways, and heavy infrastructure.

The contractor is a part of the Associated General

Contractors, National Association of Minority Contractors, and the U.S. Green

Building Council.

As soaring numbers of construction workers battle opioid addiction,

building trades leaders across the U.S. are launching solutions intended to show

contractors and union members how they can help those who are hooked on opioids.

“We don’t push someone away who gets cancer or diabetes; we

shouldn’t get rid of someone who suffers addiction,” said Thomas Gunning III,

director of labor relations for the Building Trades Employers’ Association.

“It’s a disease of the mind, and we want to help them,” he

said, according to the Boston Globe.

Yet, for decades when it came to marijuana usage, pushing

away and completely ostracizing workers is exactly what contractors and union

have done, and continue to do. So why are contractors forming coalitions to

battle opioid addiction, and trying their hardest to retain those workers that

are addicted.

But, some are arguing that this concerted effort of

retaining and offering resources to opioid addicts is because statistically this

type of drug abuse mostly affects white/Caucasians construction workers.

In recent years, many states in the U.S. have loosened up

their regulation and restriction laws related to cannabis, or marijuana, with

33 states and Washington, D.C., currently allowing it for medical reasons. Ten

of those states and D.C. allow adult recreational use.

Although, for the majority of major U.S. contractors and

labor unions, this new status of marijuana, which used to be an illegal

substance, has not persuaded them to loosen their restrictive hiring practices,

and drug testing for the substances THC & CBD.

In most cases, to align themselves with the wishes of their

clients, many large construction companies have decided that a positive drug

test is a reason not to hire or, under some conditions like an accident, a

reason to terminate employment. Even where it’s legal.

This type of enforcement of anti-drug policy has

historically punished and prevented many black construction workers from

entering the industry, and building lasting careers.

However, as far as opioid abuse is concerned, which the

federal government has described as a “crisis”, and in 2017 accounted for more

than 47,000 deaths, contractors from across America are organizing in an effort

to break down, what they describe as a “stigma” surrounding opioid abuse.

Among other goals, contractors and trade associations are

even going as far as to call for ‘Narcan’ to be available at all job sites to

help prevent opioid overdose deaths.

According to the Boston Globe, Kevin Gill, president of McCusker-Gill Inc., a

sheet-metal contractor that employs 200 workers, said Narcan will be provided

at his company’s fabrication shop.

Gill explained to the Globe, “It’s a very tough trade. Workers

may have been given a painkiller to offset an injury, and before they know it,

they have a full-blown addiction,”

“I want them to be comfortable to come to us to share their

problem and work with us to hopefully come up with a solution,” Gill went on to explain.

Studies show that opioid abuse costs construction companies

billions every year, in missed workdays, healthcare expenses, job turnover and

the costs of recruiting and retraining new employees.

Medical experts note that marijuana is significantly less

addictive and it doesn’t lead to overdoses. A recent study revealed that 93

percent of respondents found marijuana to be a more effective pain treatment

that produced fewer side effects than opioids, and is a less costly treatment

than opioids.

Given the nature of federal law versus state law, it’s hard

to tell if construction employees will ever be allowed to use prescribed

medical marijuana instead of opioids.

Moreover, construction companies under federal contracts are

responsible to adhere to restrict regulation concerning marijuana testing. For

example, if you employ individuals who use a commercial driver’s license you

have to follow the drug testing rules from the Department of Transportation and

the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA).

A public beset by potholes, failing bridges and troubled

transit systems overwhelmingly has said in surveys that it supports the $2

Trillion infrastructure investment that President Trump and Senate leader Chuck

Schumer agreed upon last Tuesday, but Congress has yet to come up with a

funding solution.

“We agreed on a number, which was very, very good, $2

trillion for infrastructure,” Schumer said. “Originally we had started a little

lower; even the president was willing to push it up to $2 trillion. And that is

a very good thing.” Schumer told the press after his meeting at the White

House.

“It was a good, positive meeting,” said Peter A. DeFazio,

chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee. “The

President spent a good time listening, and then he had things to say on his

own. It was pretty balanced. He responded to points that were made and made

points of his own. “

“I would say that 80 percent of it focused on infrastructure

writ large,” DeFazio said. “We agreed upon a broad figure of $2 trillion of

investment. Probably the largest chunk would go to roads, bridges, transit, but

we’re also going to do waste water, harbors, [and] probably include airports.

There was consensus on the need for universal broad band and some discussion of

a more efficient energy grid to transmit energy over longer distances. There

was some discussion of renewable energy, but no specifics on those.”

"The United States has not come even close to properly

investing in infrastructure for many years ... We have to invest in this

country's future and bring our infrastructure to a level better than it has

ever been before," a statement from

the White House press secretary read.

For Mr. Trump, an infrastructure deal would provide him with a bipartisan achievement he could point to while campaigning. But, Consistently, black activists, residents, and community groups identify displacement as a pressing concern. Anxieties about residential, cultural, and job displacement, are increasingly being caused by changes directly connected to gentrifying forces. These changes stem not just from individual action and market forces but also government intervention.

Gentrification is tied to historical patterns of residential

segregation, followed by the forces of gentrifying revitalization since the 1980s.

Government and public policies such as infrastructure investment have played a

key role in creating these patterns by directing public and private capital in

ways that advantage some and disadvantage other neighborhoods.

A recent study of Los Angeles and San Francisco analyzes

gentrification and displacement separately, finding that transit development’s

plays a significant role in gentrification. Although the vast majority of reporting

on transit infrastructure investment focus on the impacts of transit on real

estate value, a number of scholars are beginning to investigate the

relationship between transit investments and gentrification, with an implied

relationship to residential displacement.

Moreover, with transportation projects, and gentrification being a key issues in cities like Oakland, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia, black workers in these cities are also complaining about increased racial discrimination in the construction industry.

In Philadelphia for example, black members of Local 542, say

they have heard white supervisors throw around phrases like “worthless nigger”

on job sites, just like in the Old South. And in 2017, a black operator found a noose hanging from his crane while working at a

local power plant. In May, during the biannual general membership meeting of

Local 542, one black member seized the mic and proclaimed that he would no

longer tolerate racial epithets from the rank-and-file members of the union. “I

am not a monkey,” he said in part, according to those in attendance.

But truly how will this new infrastructure plan benefit black tradesmen and women, as well as black contractors? $2 Trillion is a huge sum of money, but will this infrastructure bill create true value for the black community in the form of well-paying jobs, and investment opportunities, is unclear given the historically racist reputation of the construction industry.

It's unclear whether or how Republicans and Democrats will

be able to find common ground on a funding source for a large infrastructure

package, something that has eluded them for years.

Despite the US context of growing income segregation, residential

and commercial gentrification is occurring in lower-income neighborhoods,

transforming the meaning of the neighborhood. And, although the displacement

discussion in the United States began with the role of the public sector and

now has returned to the same focus, it will be necessary for the black

community to overcome methodological shortcomings of disunity, and to come

together under one voice in order to effectively change the political landscape

surrounding government infrastructure investment as it relates to high-paying, skilled jobs, and gentrification.

On April 17th, the city of Los Angeles City approved a

historic Civil and Human Rights Ordinance (CF 18-0086). The ordinance co-authored

by Council President Herb J. Wesson and Council member Gil Cedillo and seconded

by other Council members, is designed to create protections for workers by overseeing

discrimination cases that occur within the city.

This is the second time in L.A.’s history that a civil

rights ordinance was up for vote by the City Council. The city’s first civil

rights ordinance was originally presented in 1955, but was voted down due in

part to the racist climate of that era.

The new ordinance gives black workers and other workers in

the city limits the ability to submit a complaint and have their issues of

injustice heard at the local level. This ordinance, 1.) Prohibits discrimination, prejudice,

intolerance and bigotry that results in denial of equal treatment of any

individual; 2.) Provides remedies accessible to complainants; 3.) Creates the

City of Los Angeles Civil and Human Rights Commission and other supporting unit

to investigate and enforce violations of civil & human rights.

On the steps of City Hall, L.A. City Council President Herb

Wesson, who co-authored the ordinance, addressed at crowd workers and members

of the Los Angeles Black Workers Centers, who celebrated the passing of the ordinance,

they helped to push, as a victory, following the vote.

"Today's vote brings us one step closer to making sure

our city's rich diversity is represented in the workplace. With this vote, we

are prioritizing vital protections for L.A.'s Black and Brown workers,

including women, immigrants, those who identify as LGBTQ, and Muslims.

Employment should be based on a person's merit, experience, and character, not

the color of their skin, where they're from, or who they love. A big thank you

to the Los Angeles Black Worker Center for their work in getting us to this

point."

As a diverse metropolis, with over 400,000 black people living

in the City of Los Angeles, the city has a duty to protect and promote public

health and safety within its boundaries and to protect its residents against

discrimination, threats and retaliation based on a real or perceived status.

The unemployment rate for Black workers in Los Angeles is 16%,

three times the national average, and yet nearly 70 percent of the state’s

workforce discrimination claims are based on race and disability. Such

discriminatory and prejudicial practices pose a substantial threat to the

health, safety and welfare of the community.

The activism of African American construction contractors in

an important, and often overlooked, piece of the broader history of racial

exclusion in the national construction industry. Black contractors seldom receive consideration

as agents of historic change. The study of black/African-American contractors

provides a distinct grassroots perspective from which to view the relationship

between black business and black labor.

African-American contractors’ historic link to black workers

was a central component in the late 1960’s and 1970’s. By the time that civil

rights activists launched mass protest that shut down construction sites in the

1960’s, black tradesmen and contractors in the San Francisco Bay area had spent roughly two

decades trying to compel the lily-white building trades unions to open their

doors to black workers.

Although the history of racial discrimination and exclusion

in organized labor unions dates back to the nineteenth century, after slavery, in places such as the Bay Area the issue became particularly

apparent in the 1940’s after World War II, with the massive wartime migration

of black Americans from the South & Midwest.

Many of the tens of

thousands of black Americans who migrated to the Bay Area in the decades after

WWII were experienced and skilled tradesmen, such as plumbers, pipe fitters,

electricians, painters, and plasterers who sought work in the booming shipyards

and expanding commercial and residential construction markets. But like other

black tradesmen that arrived in other union strongholds such as New York,

Chicago, Pittsburg, and Seattle during and after WWII, these tradesmen found

themselves subjugated to severe racial discrimination, and restrictive labor

unions.

When confronted with union discrimination, black tradesmen

responded in a variety of ways: some looked for work in other industries, or

accepted lower-paying and less-skilled construction work as laborers; others

sought assistance from civil rights organization, and government agencies, but

these entities did not produce substantial and permanent gains for black

tradesmen. However, skilled black tradesmen could also exercise another option –

contracting.

The decision to become contractors grew out of constant

severe discrimination, and economic necessity. By setting up shop for themselves,

black tradesmen who took the state contractors’ licensing exam improved their

chances of avoiding union discrimination and gaining a greater degree of

control over their work lives.

As black contractors bettered their chances to earn a living

in the construction industry, they also created important roles for themselves

as employers and mentors for black tradesmen who were curtailed by labor unions

in their search for work and training opportunities. Through their close

relationships with black tradesmen, black contractors established an important

link to the growing Bay Area black communities.

As small, new contractors, starting out for the first time post World War II in the vast construction industry, black contractors were mostly sole

proprietorship's , and the owner was usually his own best worker. The majority

of black contractors in this period built one or two houses a year and spent

most of their time performing repairs and ‘patch work.’

In fact, according to a 1968 estimate of the Small Business

Administration (SBA), only 8,000 of America’s approximately 870,000

construction firms were black or minority-owned. The disparity between black

and white contractors widened throughout the 1960’s as, in the Bay Area and

across the United States, residential construction begin to stagnant, while

large-scale, especially government-financed construction expanded.

Moreover, in 1969 the presidential Cabinet on Construction

predicted that the “United States will put in place in the next 30 years as much construction as there has been from the founding of the Republic to now.” Yet black contractors stood to gain little

from the construction boom.

According to a 1967 report, for instance, black/minority

contractors accounted for less than $500 million of the $80 billion U.S.

construction industry. This disparity was evident in the Bay Area, where by

1968 not one of the approximately 125 black contractors in the region was working

on a large publicly financed job.

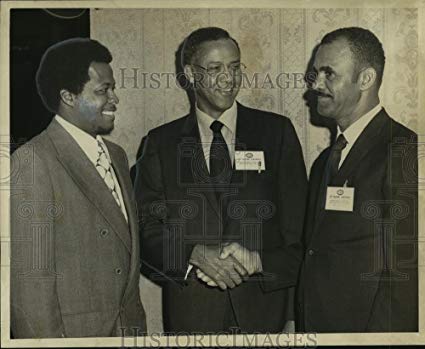

Joseph Dedro

enters the industry

In cities across the United States, a small number of black

contractors and business leaders sought to make changes for the better of blacks in the

construction industry. Chief among them was Joseph Debro. Born in Jackson,

Mississippi, Debro came to the Bay Area with his parents after WWII, and became

a contractor.

Debro entered into construction with advanced university training,

after obtaining an undergraduate degree in engineering and a master’s degree in

biochemistry from the University of California. Debro became interested in

large-scale construction projects while working as an engineer on the

construction of Interstate 580 in the East Bay during the 1950’s. In the years

following, he developed a keen interest in the problems confronting black

contractors and emerged as one of the leading advocates for black contractors.

Beginning in the 1960s, Debro focused his work on overcoming

the four major obstacles that prevented black contractors from expanding their

companies and obtaining lucrative government contracts: Lack of Skilled Labor,

Lack of Technical Management Skills, Lack of Capital, and Bonding Requirements.

The lack of skilled workers for instance, was a direct result of the building

trades unions, which controlled the primary avenue to apprenticeship training.

But, the fourth obstacle – bonding requirements – proved the most troublesome

for black contractors to overcome.

Because of their historical lack of capital and technical

training, black contractors claimed that the bonding requirements created a

vicious cycle in which most black contractors lacked experience, capital, and

managerial capabilities required to obtain the bonds they needed to quality for

various types of projects that would give them the experience needed to qualify.

But, Surety companies that issued bonds, claimed that they also

considered other factors when deciding whether to issue a bond or not, such as

the “three C’s”: Character, Capital, and Capacity. Although,in a unpublished 1968

memorandum, the American Insurance Association stated that it believed “that it

will serve NO USEFUL PURPOSE, economic or sociological, for surety companies to

issue contract bonds indiscriminately to all applicants, qualified or not.”

Black contractors considered such practices as examples of

racial discrimination and frequently protested that the industry perpetuated a

double standard. As a result, Debro and other black contractors testified to congress that

surety companies denied bonds to qualified black contactors, but these charges

of overt discrimination were often difficult to prove because the majority of

black contractors could not meet the capital requirements of most bonding

companies anyways.

Debro believed something needed to change, and that the free

market could not solve the bonding problems, nor the other obstacles that

limited black contractor’s opportunities. He felt that “all these problems are

aggravated by the inaction of city leaders (working) in the unions, government, private

business, and universities who should be devoting their time to mobilizing

resources on a local level to cope with the exclusion of minorities from all

phases of the construction industry.”

However, before black contractors could expect to receive external

assistance, Debro felt that they needed to organize themselves on a larger

scale.

Joe meets Ray

In the Bay Area, protesters begin to target the construction

of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System (BART), a billion-dollar project that was

scheduled to take five years to complete. Much of BART’s construction was

located in some of the poorest neighborhoods in Oakland and San Francisco, and

local residents made it clear that they would not stand by idly while white

construction crews performed work and earned middle-class wages.

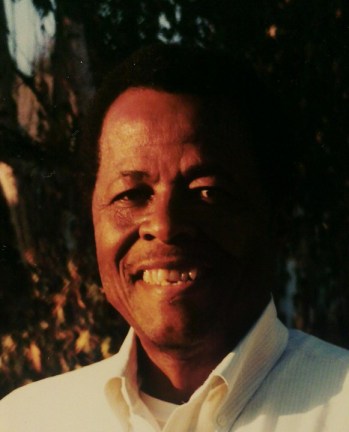

And it was in that tumultuous atmosphere that a black

electrical contractor named Raymon Dones walked into Joseph Debro’s office in

1966. Although Ray was not seeking a contract on the BART project, he hoped

that Joe Debro, who was at the time, serving as the executive director of the Oakland Small

Business Development Center (OSBDC), could help him obtain a loan so that he

could bid on other government projects.

Born in Marshall, Texas, Raymon Dones moved to the Bay Area in

1950, and in 1953 he established Dones Electric (which later became Aladdin

Electric) in Berkley, CA. Like many

other black contractors in the Bay Area during this period, Aladdin Electric

procured steady employment on small residential buildings, and by the mid-1960’s

he had a workforce of six full-time electricians – all of whom were black.

Yet when the residential construction market slowed down, Ray was unable to obtain surety bonds to bid on lucrative government –financed

construction projects, and as a result he had to lay off two of his

electricians. Hoping to avoid further cutbacks and looking to expand his

company, he visited Joe Debro at the OSBDC.

Ray Dones and Joe Debro immediately hit it off , and instead of

arranging a loan they discussed forming an organization that could assist black

contractors in making the transition from small residential construction to

larger public-sector projects. Shortly thereafter,

Dones and Debro formed the General and Specialty Contractors Association

(GSCA), which was among the first black contractor associations in the United

States.

The founders of the GSCA hoped their organization would appeal to small-scale contractors by offering a variety of programs designed to provide the managerial and technical assistance needed to compete with more established firms on large and publicly financed projects.

In its first three

years, the GSCA developed programs to provide information to black contractors

about publicly funded contracts, and assisted inexperienced members with

preparing estimates, and business procedures on jobs in progress, as well as mediated in labor disputes.

And in 1968, six GSCA members pooled their resources to form

Trans-Bay Engineering and Builders, Inc., a general contracting firm that they

hoped could compete with the larger white-owned contracting companies in the

Bay Area.

Creating

opportunities & training the Bay

The GSCA also placed emphasis on training black workers for

the building trades. Because of their need for skilled tradesmen, the GSCA

contractors made training black and other races of workers an important part of

their mission. GSCA contractors stressed

that the historical link between black contractors and the unions’ history of

discrimination caused young blacks to avoid union-administered apprenticeship

programs. GSCA leaders insisted, most construction workers learned trade skills

through on-the-job training - something black workers acquired while working

for black contractors.

Black contractors sought a model for integrating

construction training into the black community, which would at the same time eliminate

the barriers that limited their access to jobs. By the summer of 1967, the GSCA

and the OSBDC had drafted a ‘community action program’ for Oakland that

proposed the of use black contractors as the primary vehicle for training black

workers.

The plan called for

an “On-the-job Training Credit Bank” that would provide training and employment

for approximately six-hundred workers while creating an economically viable

group of building contractors who would be able to carry-on the training of black

workers, and assist contractors with increaing their business skills.

After the program was rejected financing by the federal

government. Dones and Debro eventually found proper funding, from private

philanthropies, such as the Ford Foundation, which provided a 3-year, $300,000 grant

in 1968, so that the Credit Bank could help cover the costs of training black

construction workers, while simultaneously increasing the bond capacity of black

contractors.

The Oakland Bonding Assistance Program, as it was named, produced immediate results. Within a few months of operation, the program made 35 bond-related advances totaling $287,544, to black contractors to secure bonds needed to bid on government projects.

Trans-Bay Engineers and Builders was the

program’s biggest client. It was able to obtain an interest-free $50,000 loan

from the fund to secure a bond on the construction of the West Oakland Health

Center, a contract that the company would have otherwise lost because the surety

company had cancelled company's bond at the eleventh hour.

The GSCA also formed a program called PREP (Property

Rehabilitation Employment Project), and formed a cooperation with the Alameda County

Building and Construction Trade Council, which was eventually financed with grants

for the Department of Labor and the Ford Foundation. One of PREP's mission was to help black

tradesmen with previous construction experience attain journeyman status. And,

in 1969 PREP provided construction training to hundreds of black youth who were unable to

get into union apprenticeship programs.

The success of the these programs helped GSCA become an integral component of the Oakland

Redevelopment Agency’s (ORA) attempts to maximize black participation in its

West Oakland projects. GSCA helped black and other races of contractors secure “turnkey”

agreements with the Oakland Housing Authority.

This level of participation had a direct impact on black

employment on redevelopment projects. And in 1970, Joe Debro reported that 200 new

jobs had been generated and black tradesmen work hours and wages roughly doubled,

and “generated more non-white union journeymen in the in the high-wage crafts

than in the entire history of the local hiring-hall process.”

The GSCA’s pilot project in the Bay Area became a model for

programs across the Unuted States, and helped Bay Area contractors take a lead role in the

founding a national black contractors association to build upon their success.

Based on early returns, and success in Oakland, the Ford Foundation helped

launch similar programs in New York, Boston, and Cleveland.

By organizing themselves into collective associations and

advancing their program in Oakland, Joe Dedro and Ray Dones’ programs and

policies had gone on to effect the national agendas, and have in recent years inspired black

contractors and other minority contractors to create organizations that

successfully address discrimination in the historically racist construction

industry.

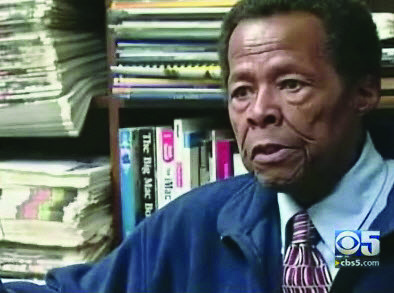

JOE AND RAY'S LASTING LEGACIES...

After retirement, Joe Debro never ceased to be active in his community and began writing for several community newspapers, including the San Francisco Bay View, a national Black newspaper; the East Bay Express; and the Oakland Post.

He continued to mentor and advocate for young business people and contractors, trying to break down the barriers of racial exclusion in trade unions and government contracting.

Joe Debro struggled to insure that all of his children

acquired an education, and all three of his sons not only graduated college,

but attained Master’s degrees. The middle son, Karl, earned his doctorate a

year before his father’s death.

AAs for Ray Dones, during his 20 years of business, Ray was ranked in the Top-6 black construction contractors in the United States, completing over $200 million worth of construction contracts. He made history in 1970 when he partnered the company he helped create, Tran-Bay, with Turner Construction to create the first joint venture project between a major firm and a minority builder.

In 1999, Engineering New-Record magazine named Raymon Dones as one of the most influential people in the construction industry

over a 125-years period.

Ray continued his activism in the community throughout his lifetime. He served on the National Urban League, UC Regents of Advisors, the Oakland Chamber of Commerce, and as a volunteer with the Museum of African-American Technology (MAAT)

BOTH MEN WILL TRULY BE MISSED BUT THEIR LEGACIES AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE BETTERMENT OF BLACK CONTRACTORS & BLACK TRADESMEN WILL LIVE ON AND NEVER BE FORGOTTEN!