Ray's article

A public beset by potholes, failing bridges and troubled

transit systems overwhelmingly has said in surveys that it supports the $2

Trillion infrastructure investment that President Trump and Senate leader Chuck

Schumer agreed upon last Tuesday, but Congress has yet to come up with a

funding solution.

“We agreed on a number, which was very, very good, $2

trillion for infrastructure,” Schumer said. “Originally we had started a little

lower; even the president was willing to push it up to $2 trillion. And that is

a very good thing.” Schumer told the press after his meeting at the White

House.

“It was a good, positive meeting,” said Peter A. DeFazio,

chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee. “The

President spent a good time listening, and then he had things to say on his

own. It was pretty balanced. He responded to points that were made and made

points of his own. “

“I would say that 80 percent of it focused on infrastructure

writ large,” DeFazio said. “We agreed upon a broad figure of $2 trillion of

investment. Probably the largest chunk would go to roads, bridges, transit, but

we’re also going to do waste water, harbors, [and] probably include airports.

There was consensus on the need for universal broad band and some discussion of

a more efficient energy grid to transmit energy over longer distances. There

was some discussion of renewable energy, but no specifics on those.”

"The United States has not come even close to properly

investing in infrastructure for many years ... We have to invest in this

country's future and bring our infrastructure to a level better than it has

ever been before," a statement from

the White House press secretary read.

For Mr. Trump, an infrastructure deal would provide him with a bipartisan achievement he could point to while campaigning. But, Consistently, black activists, residents, and community groups identify displacement as a pressing concern. Anxieties about residential, cultural, and job displacement, are increasingly being caused by changes directly connected to gentrifying forces. These changes stem not just from individual action and market forces but also government intervention.

Gentrification is tied to historical patterns of residential

segregation, followed by the forces of gentrifying revitalization since the 1980s.

Government and public policies such as infrastructure investment have played a

key role in creating these patterns by directing public and private capital in

ways that advantage some and disadvantage other neighborhoods.

A recent study of Los Angeles and San Francisco analyzes

gentrification and displacement separately, finding that transit development’s

plays a significant role in gentrification. Although the vast majority of reporting

on transit infrastructure investment focus on the impacts of transit on real

estate value, a number of scholars are beginning to investigate the

relationship between transit investments and gentrification, with an implied

relationship to residential displacement.

Moreover, with transportation projects, and gentrification being a key issues in cities like Oakland, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia, black workers in these cities are also complaining about increased racial discrimination in the construction industry.

In Philadelphia for example, black members of Local 542, say

they have heard white supervisors throw around phrases like “worthless nigger”

on job sites, just like in the Old South. And in 2017, a black operator found a noose hanging from his crane while working at a

local power plant. In May, during the biannual general membership meeting of

Local 542, one black member seized the mic and proclaimed that he would no

longer tolerate racial epithets from the rank-and-file members of the union. “I

am not a monkey,” he said in part, according to those in attendance.

But truly how will this new infrastructure plan benefit black tradesmen and women, as well as black contractors? $2 Trillion is a huge sum of money, but will this infrastructure bill create true value for the black community in the form of well-paying jobs, and investment opportunities, is unclear given the historically racist reputation of the construction industry.

It's unclear whether or how Republicans and Democrats will

be able to find common ground on a funding source for a large infrastructure

package, something that has eluded them for years.

Despite the US context of growing income segregation, residential

and commercial gentrification is occurring in lower-income neighborhoods,

transforming the meaning of the neighborhood. And, although the displacement

discussion in the United States began with the role of the public sector and

now has returned to the same focus, it will be necessary for the black

community to overcome methodological shortcomings of disunity, and to come

together under one voice in order to effectively change the political landscape

surrounding government infrastructure investment as it relates to high-paying, skilled jobs, and gentrification.

On April 17th, the city of Los Angeles City approved a

historic Civil and Human Rights Ordinance (CF 18-0086). The ordinance co-authored

by Council President Herb J. Wesson and Council member Gil Cedillo and seconded

by other Council members, is designed to create protections for workers by overseeing

discrimination cases that occur within the city.

This is the second time in L.A.’s history that a civil

rights ordinance was up for vote by the City Council. The city’s first civil

rights ordinance was originally presented in 1955, but was voted down due in

part to the racist climate of that era.

The new ordinance gives black workers and other workers in

the city limits the ability to submit a complaint and have their issues of

injustice heard at the local level. This ordinance, 1.) Prohibits discrimination, prejudice,

intolerance and bigotry that results in denial of equal treatment of any

individual; 2.) Provides remedies accessible to complainants; 3.) Creates the

City of Los Angeles Civil and Human Rights Commission and other supporting unit

to investigate and enforce violations of civil & human rights.

On the steps of City Hall, L.A. City Council President Herb

Wesson, who co-authored the ordinance, addressed at crowd workers and members

of the Los Angeles Black Workers Centers, who celebrated the passing of the ordinance,

they helped to push, as a victory, following the vote.

"Today's vote brings us one step closer to making sure

our city's rich diversity is represented in the workplace. With this vote, we

are prioritizing vital protections for L.A.'s Black and Brown workers,

including women, immigrants, those who identify as LGBTQ, and Muslims.

Employment should be based on a person's merit, experience, and character, not

the color of their skin, where they're from, or who they love. A big thank you

to the Los Angeles Black Worker Center for their work in getting us to this

point."

As a diverse metropolis, with over 400,000 black people living

in the City of Los Angeles, the city has a duty to protect and promote public

health and safety within its boundaries and to protect its residents against

discrimination, threats and retaliation based on a real or perceived status.

The unemployment rate for Black workers in Los Angeles is 16%,

three times the national average, and yet nearly 70 percent of the state’s

workforce discrimination claims are based on race and disability. Such

discriminatory and prejudicial practices pose a substantial threat to the

health, safety and welfare of the community.

The activism of African American construction contractors in

an important, and often overlooked, piece of the broader history of racial

exclusion in the national construction industry. Black contractors seldom receive consideration

as agents of historic change. The study of black/African-American contractors

provides a distinct grassroots perspective from which to view the relationship

between black business and black labor.

African-American contractors’ historic link to black workers

was a central component in the late 1960’s and 1970’s. By the time that civil

rights activists launched mass protest that shut down construction sites in the

1960’s, black tradesmen and contractors in the San Francisco Bay area had spent roughly two

decades trying to compel the lily-white building trades unions to open their

doors to black workers.

Although the history of racial discrimination and exclusion

in organized labor unions dates back to the nineteenth century, after slavery, in places such as the Bay Area the issue became particularly

apparent in the 1940’s after World War II, with the massive wartime migration

of black Americans from the South & Midwest.

Many of the tens of

thousands of black Americans who migrated to the Bay Area in the decades after

WWII were experienced and skilled tradesmen, such as plumbers, pipe fitters,

electricians, painters, and plasterers who sought work in the booming shipyards

and expanding commercial and residential construction markets. But like other

black tradesmen that arrived in other union strongholds such as New York,

Chicago, Pittsburg, and Seattle during and after WWII, these tradesmen found

themselves subjugated to severe racial discrimination, and restrictive labor

unions.

When confronted with union discrimination, black tradesmen

responded in a variety of ways: some looked for work in other industries, or

accepted lower-paying and less-skilled construction work as laborers; others

sought assistance from civil rights organization, and government agencies, but

these entities did not produce substantial and permanent gains for black

tradesmen. However, skilled black tradesmen could also exercise another option –

contracting.

The decision to become contractors grew out of constant

severe discrimination, and economic necessity. By setting up shop for themselves,

black tradesmen who took the state contractors’ licensing exam improved their

chances of avoiding union discrimination and gaining a greater degree of

control over their work lives.

As black contractors bettered their chances to earn a living

in the construction industry, they also created important roles for themselves

as employers and mentors for black tradesmen who were curtailed by labor unions

in their search for work and training opportunities. Through their close

relationships with black tradesmen, black contractors established an important

link to the growing Bay Area black communities.

As small, new contractors, starting out for the first time post World War II in the vast construction industry, black contractors were mostly sole

proprietorship's , and the owner was usually his own best worker. The majority

of black contractors in this period built one or two houses a year and spent

most of their time performing repairs and ‘patch work.’

In fact, according to a 1968 estimate of the Small Business

Administration (SBA), only 8,000 of America’s approximately 870,000

construction firms were black or minority-owned. The disparity between black

and white contractors widened throughout the 1960’s as, in the Bay Area and

across the United States, residential construction begin to stagnant, while

large-scale, especially government-financed construction expanded.

Moreover, in 1969 the presidential Cabinet on Construction

predicted that the “United States will put in place in the next 30 years as much construction as there has been from the founding of the Republic to now.” Yet black contractors stood to gain little

from the construction boom.

According to a 1967 report, for instance, black/minority

contractors accounted for less than $500 million of the $80 billion U.S.

construction industry. This disparity was evident in the Bay Area, where by

1968 not one of the approximately 125 black contractors in the region was working

on a large publicly financed job.

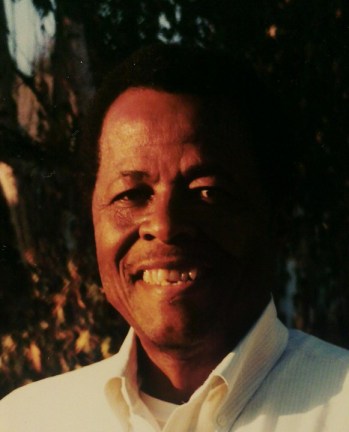

Joseph Dedro

enters the industry

In cities across the United States, a small number of black

contractors and business leaders sought to make changes for the better of blacks in the

construction industry. Chief among them was Joseph Debro. Born in Jackson,

Mississippi, Debro came to the Bay Area with his parents after WWII, and became

a contractor.

Debro entered into construction with advanced university training,

after obtaining an undergraduate degree in engineering and a master’s degree in

biochemistry from the University of California. Debro became interested in

large-scale construction projects while working as an engineer on the

construction of Interstate 580 in the East Bay during the 1950’s. In the years

following, he developed a keen interest in the problems confronting black

contractors and emerged as one of the leading advocates for black contractors.

Beginning in the 1960s, Debro focused his work on overcoming

the four major obstacles that prevented black contractors from expanding their

companies and obtaining lucrative government contracts: Lack of Skilled Labor,

Lack of Technical Management Skills, Lack of Capital, and Bonding Requirements.

The lack of skilled workers for instance, was a direct result of the building

trades unions, which controlled the primary avenue to apprenticeship training.

But, the fourth obstacle – bonding requirements – proved the most troublesome

for black contractors to overcome.

Because of their historical lack of capital and technical

training, black contractors claimed that the bonding requirements created a

vicious cycle in which most black contractors lacked experience, capital, and

managerial capabilities required to obtain the bonds they needed to quality for

various types of projects that would give them the experience needed to qualify.

But, Surety companies that issued bonds, claimed that they also

considered other factors when deciding whether to issue a bond or not, such as

the “three C’s”: Character, Capital, and Capacity. Although,in a unpublished 1968

memorandum, the American Insurance Association stated that it believed “that it

will serve NO USEFUL PURPOSE, economic or sociological, for surety companies to

issue contract bonds indiscriminately to all applicants, qualified or not.”

Black contractors considered such practices as examples of

racial discrimination and frequently protested that the industry perpetuated a

double standard. As a result, Debro and other black contractors testified to congress that

surety companies denied bonds to qualified black contactors, but these charges

of overt discrimination were often difficult to prove because the majority of

black contractors could not meet the capital requirements of most bonding

companies anyways.

Debro believed something needed to change, and that the free

market could not solve the bonding problems, nor the other obstacles that

limited black contractor’s opportunities. He felt that “all these problems are

aggravated by the inaction of city leaders (working) in the unions, government, private

business, and universities who should be devoting their time to mobilizing

resources on a local level to cope with the exclusion of minorities from all

phases of the construction industry.”

However, before black contractors could expect to receive external

assistance, Debro felt that they needed to organize themselves on a larger

scale.

Joe meets Ray

In the Bay Area, protesters begin to target the construction

of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System (BART), a billion-dollar project that was

scheduled to take five years to complete. Much of BART’s construction was

located in some of the poorest neighborhoods in Oakland and San Francisco, and

local residents made it clear that they would not stand by idly while white

construction crews performed work and earned middle-class wages.

And it was in that tumultuous atmosphere that a black

electrical contractor named Raymon Dones walked into Joseph Debro’s office in

1966. Although Ray was not seeking a contract on the BART project, he hoped

that Joe Debro, who was at the time, serving as the executive director of the Oakland Small

Business Development Center (OSBDC), could help him obtain a loan so that he

could bid on other government projects.

Born in Marshall, Texas, Raymon Dones moved to the Bay Area in

1950, and in 1953 he established Dones Electric (which later became Aladdin

Electric) in Berkley, CA. Like many

other black contractors in the Bay Area during this period, Aladdin Electric

procured steady employment on small residential buildings, and by the mid-1960’s

he had a workforce of six full-time electricians – all of whom were black.

Yet when the residential construction market slowed down, Ray was unable to obtain surety bonds to bid on lucrative government –financed

construction projects, and as a result he had to lay off two of his

electricians. Hoping to avoid further cutbacks and looking to expand his

company, he visited Joe Debro at the OSBDC.

Ray Dones and Joe Debro immediately hit it off , and instead of

arranging a loan they discussed forming an organization that could assist black

contractors in making the transition from small residential construction to

larger public-sector projects. Shortly thereafter,

Dones and Debro formed the General and Specialty Contractors Association

(GSCA), which was among the first black contractor associations in the United

States.

The founders of the GSCA hoped their organization would appeal to small-scale contractors by offering a variety of programs designed to provide the managerial and technical assistance needed to compete with more established firms on large and publicly financed projects.

In its first three

years, the GSCA developed programs to provide information to black contractors

about publicly funded contracts, and assisted inexperienced members with

preparing estimates, and business procedures on jobs in progress, as well as mediated in labor disputes.

And in 1968, six GSCA members pooled their resources to form

Trans-Bay Engineering and Builders, Inc., a general contracting firm that they

hoped could compete with the larger white-owned contracting companies in the

Bay Area.

Creating

opportunities & training the Bay

The GSCA also placed emphasis on training black workers for

the building trades. Because of their need for skilled tradesmen, the GSCA

contractors made training black and other races of workers an important part of

their mission. GSCA contractors stressed

that the historical link between black contractors and the unions’ history of

discrimination caused young blacks to avoid union-administered apprenticeship

programs. GSCA leaders insisted, most construction workers learned trade skills

through on-the-job training - something black workers acquired while working

for black contractors.

Black contractors sought a model for integrating

construction training into the black community, which would at the same time eliminate

the barriers that limited their access to jobs. By the summer of 1967, the GSCA

and the OSBDC had drafted a ‘community action program’ for Oakland that

proposed the of use black contractors as the primary vehicle for training black

workers.

The plan called for

an “On-the-job Training Credit Bank” that would provide training and employment

for approximately six-hundred workers while creating an economically viable

group of building contractors who would be able to carry-on the training of black

workers, and assist contractors with increaing their business skills.

After the program was rejected financing by the federal

government. Dones and Debro eventually found proper funding, from private

philanthropies, such as the Ford Foundation, which provided a 3-year, $300,000 grant

in 1968, so that the Credit Bank could help cover the costs of training black

construction workers, while simultaneously increasing the bond capacity of black

contractors.

The Oakland Bonding Assistance Program, as it was named, produced immediate results. Within a few months of operation, the program made 35 bond-related advances totaling $287,544, to black contractors to secure bonds needed to bid on government projects.

Trans-Bay Engineers and Builders was the

program’s biggest client. It was able to obtain an interest-free $50,000 loan

from the fund to secure a bond on the construction of the West Oakland Health

Center, a contract that the company would have otherwise lost because the surety

company had cancelled company's bond at the eleventh hour.

The GSCA also formed a program called PREP (Property

Rehabilitation Employment Project), and formed a cooperation with the Alameda County

Building and Construction Trade Council, which was eventually financed with grants

for the Department of Labor and the Ford Foundation. One of PREP's mission was to help black

tradesmen with previous construction experience attain journeyman status. And,

in 1969 PREP provided construction training to hundreds of black youth who were unable to

get into union apprenticeship programs.

The success of the these programs helped GSCA become an integral component of the Oakland

Redevelopment Agency’s (ORA) attempts to maximize black participation in its

West Oakland projects. GSCA helped black and other races of contractors secure “turnkey”

agreements with the Oakland Housing Authority.

This level of participation had a direct impact on black

employment on redevelopment projects. And in 1970, Joe Debro reported that 200 new

jobs had been generated and black tradesmen work hours and wages roughly doubled,

and “generated more non-white union journeymen in the in the high-wage crafts

than in the entire history of the local hiring-hall process.”

The GSCA’s pilot project in the Bay Area became a model for

programs across the Unuted States, and helped Bay Area contractors take a lead role in the

founding a national black contractors association to build upon their success.

Based on early returns, and success in Oakland, the Ford Foundation helped

launch similar programs in New York, Boston, and Cleveland.

By organizing themselves into collective associations and

advancing their program in Oakland, Joe Dedro and Ray Dones’ programs and

policies had gone on to effect the national agendas, and have in recent years inspired black

contractors and other minority contractors to create organizations that

successfully address discrimination in the historically racist construction

industry.

JOE AND RAY'S LASTING LEGACIES...

After retirement, Joe Debro never ceased to be active in his community and began writing for several community newspapers, including the San Francisco Bay View, a national Black newspaper; the East Bay Express; and the Oakland Post.

He continued to mentor and advocate for young business people and contractors, trying to break down the barriers of racial exclusion in trade unions and government contracting.

Joe Debro struggled to insure that all of his children

acquired an education, and all three of his sons not only graduated college,

but attained Master’s degrees. The middle son, Karl, earned his doctorate a

year before his father’s death.

AAs for Ray Dones, during his 20 years of business, Ray was ranked in the Top-6 black construction contractors in the United States, completing over $200 million worth of construction contracts. He made history in 1970 when he partnered the company he helped create, Tran-Bay, with Turner Construction to create the first joint venture project between a major firm and a minority builder.

In 1999, Engineering New-Record magazine named Raymon Dones as one of the most influential people in the construction industry

over a 125-years period.

Ray continued his activism in the community throughout his lifetime. He served on the National Urban League, UC Regents of Advisors, the Oakland Chamber of Commerce, and as a volunteer with the Museum of African-American Technology (MAAT)

BOTH MEN WILL TRULY BE MISSED BUT THEIR LEGACIES AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE BETTERMENT OF BLACK CONTRACTORS & BLACK TRADESMEN WILL LIVE ON AND NEVER BE FORGOTTEN!

A Project labor agreements (PLAs) also known as a Community

Workforce Agreement, is a pre-hire collective bargaining agreement with labor

organizations that establishes the terms and conditions of specific

construction project.

These types of agreements are often a point of contention in

the construction industry, particularly between private & union contractors, and are often credited for hurting black contractors ability to bid on public projects. These agreements are so contentious that builders are trying to get

government-mandated PLAs banned at both the state and federal level.

In short, before any workers are hired on the project,

construction unions have bargaining rights to determine the wage rates and

benefits of all employees working on the particular project and often force

non-union contractors to agree to the provisions of the agreement through

political influence.

When signed, the terms of the agreement apply to all

contractors and subcontractors who successfully bid on the project, and

subsequently supersedes any existing collective bargaining agreements.

In other words, the deals govern just about anything related

to how both union and nonunion workers are hired and treated on the job.

The agreements have been in use in the United States since

the 1930s, and first became the subject of debate in the 1980s, for their use

on publicly funded projects. In these instances, government entities made

signing PLAs a condition of working on taxpayer funded projects.

Contractors are most likely to encounter PLAs on publicly

funded projects. But in union strongholds like New York City and Los Angeles, it

is very common to find a PLA in place on major private construction projects,

such as the Los Angeles Stadium/Entertainment District at Hollywood Park that is

a private. A PLA was also entered into for the second phase of the $25 billion

Hudson Yards project in Manhattan, after several lawsuits were filed in New

York.

Opponents of PLAs state that the agreements impact

competition for project bids, which can lead to higher costs, particularly

labor cost. Also, PLA’s reduce the number of potential bidders as non-union

contractors, especially black contractors, are less likely to bid due to the

potential restrictions a PLA would pose.

But according to union supporters, PLAs can be used by

public project owners like school boards or city councils to set goals for

creating local jobs and achieving social welfare goals through the construction

projects.

PLAs may include provisions for targeted hiring and union apprenticeship

ratio provisions. According to proponents, by including requirements for a

certain proportion of local workers to enter union apprenticeship programs

working on the construction program, PLAs can be used to help local workers

gain skills.

Those who oppose PLAs have pointed to examples such as the

construction of the Yankee Stadium and the Washington Nationals Ballpark, for

both of which community focused hiring agreements were in place but the goals

of local hiring and resources to be provided to the community were not met.

How PLA’s effect

to Black Contractors & Black Workers

The National Black Chamber of Commerce opposes the use of PLAs due to the low numbers of black union members in the construction industry. According to the NBCC, implementing PLAs leads to discrimination against black workers who are generally non-union.

NBCC Policy Statement on Project Labor Agreements:

“It is the policy of the National Black Chamber of Commerce,

Inc. to oppose Project Labor Agreements. This opposition is based on the fact

that African American workers are significantly underrepresented in all crafts

of construction union shops. This problem has been persistent during the past

decades and there appears to be no type of improvement coming within the next

ten years.

There have been rouses of diversity pre-apprenticeship

training programs during the past twenty years but no increase in diversity at

the apprenticeship to journeymen levels. The higher incidence of union labor in

the construction industry, the lower African American employment will be

realized. This is constant throughout the nation.

Also, and equally important, the higher use of union shops

brings a correlated decrease in the amount of Black owned businesses being involved

on a worksite.”

The problem with a project labor agreement, according to

critics, is that contractors hire workers through hiring halls run by the

building trades unions for their members, which are predominately white and

have always been segregated.

As a result, African-American construction workers – no

matter how experienced – tend not to be union members and have little access to

union jobs. Black workers tend to work for non-union, Black-owned small construction

firms. Those jobs could be eliminated by the use of PLA's.

It is also clear that the construction trade labor unions have been, and remain, a serious obstacle to the participation of black owned contractors in the construction industry. They intimidate black-owned construction firms to discourage utilization of black construction workers, discourage workforce development in higher-paying skilled trades, send less qualified workers to black-owned construction firms, and discriminate against black workers in apprenticeship programs. The execution of project labor agreement has also been cited as disadvantageous to black-owned construction companies and their desire to employ black workers.

According to Harry Alford, President of the National Black

Chamber of Commerce:

Project labor agreements handicap nonunion contractors who

wish to bid on federal projects by imposing burdensome requirements on them.

Under a PLA, an open shop contractor could be required to employ workers from

union hiring halls, acquire apprentices from union apprentice programs, and

require employees to pay union dues. As an example, he cited Nationals Park,

which, was built under a PLA. Although it is in Southeast DC, “very few people

in southeast Washington ”worked on it. As Alford noted, most minority

contractors are nonunion.

Mr. Alford is completely right. An October 2007 report by the District

Economic Empowerment Coalition found that despite a government-mandated PLA

requiring that at least 50 percent of journeyman hours on the Nationals Park

project be performed by DC residents

(many of whom are black), non-DC residents worked over 70 percent of the

journeyman hours! The report also found

that not only did contractors subject to the Nationals Park PLA failed to meet

the hiring requirements, but they also failed to provide the training and

apprenticeship opportunities they promised the District.

What do the studies say?

Several studies by the Beacon Hill Institute (BHI) at

Suffolk University in Boston, Massachusetts have concluded that PLAs increase

construction costs. Studies examining the impact of PLAs on school construction

in several states have found that where PLAs were in use construction costs

were increased. In 2003, a study by the institute found that use of PLAs

created a cost increase of almost 14% increase compared to a non-PLA project. The

following year their study of PLAs in Connecticut found that PLAs increased

costs by nearly 18%. A May 2006 study by BHI found that the use of PLAs on

school construction projects in New York between 1996 and 2004 increased

construction costs by 20%.

In 2010, the New Jersey Department of Labor studied the

impact of government-mandated PLAs on the cost of school construction in New

Jersey during 2008, and also found that school construction projects where a

PLA was used had higher costs, per square foot and per student, than those

without a PLA.

Yet, construction trade unions support PLA’s, and state that

rather than increase cost, the agreements provide benefits to the community,

with higher paying jobs, and apprenticeship opportunities. According to unions,

project cost is directly related to the complexity of a project, not the

existence of an agreement.

Are union workers paid much more than nonunion workers? Not

really. Including benefits and excluding union dues, most nonunion contractors

(commonly called “merit contractors”) pay about the same as non-union

contractors because they want to keep their good employees; the same method

used by union contractors.

Some are arguing that there’s more at stake than just the

cost of a project, and that PLA’s are outright unjust. Nationally, fewer than

one in seven construction workers are in a union. What this means is that

imposing a project labor agreement may deny work to six of seven local

construction workers.

BOTTOM LINE

In 2009, President Barack Obama signed executive order

13502, which urges federal agencies to consider mandating the use of PLAs on

federal construction projects costing $25 million or more on a case-by-case

basis.

PLA’s disproportionately hurt black works and black

contractors.

The debate has been heating up, as House Republican

lawmakers have been recently urging President Trump to rescind Executive Order

13502. In a letter signed by 44 republicans to President Trump, they urged the

following:

“We have strong concerns with Executive Order 13502 and

believe that rescinding this negative policy is in line with your plans to cut

red tape in Washington and across our government agencies.

To create the conditions for innovation and free enterprise,

we must promote open competition, efficiency, fairness and equality in

government contracting. Mandating, or even encouraging PLAs needlessly limits

the pool of experienced and qualified bidders able to deliver the best possible

product to taxpayers at the best possible price… Ensuring that PLAs are not

encouraged on our federal projects will send a clear message to the

construction industry that this administration is committed to merit-based,

cost-effective projects that provide the best benefit for hardworking

taxpayers.”

Construction industry-friendly President Donald Trump has

not indicated he will make a move on this issue.

In 1963, the failure of mainstream civil rights groups to negotiate

a workable plan for desegregating the construction industry inspired more

militant activists to increase pressure on mayors and union leaders of the

building trades unions across the United States.

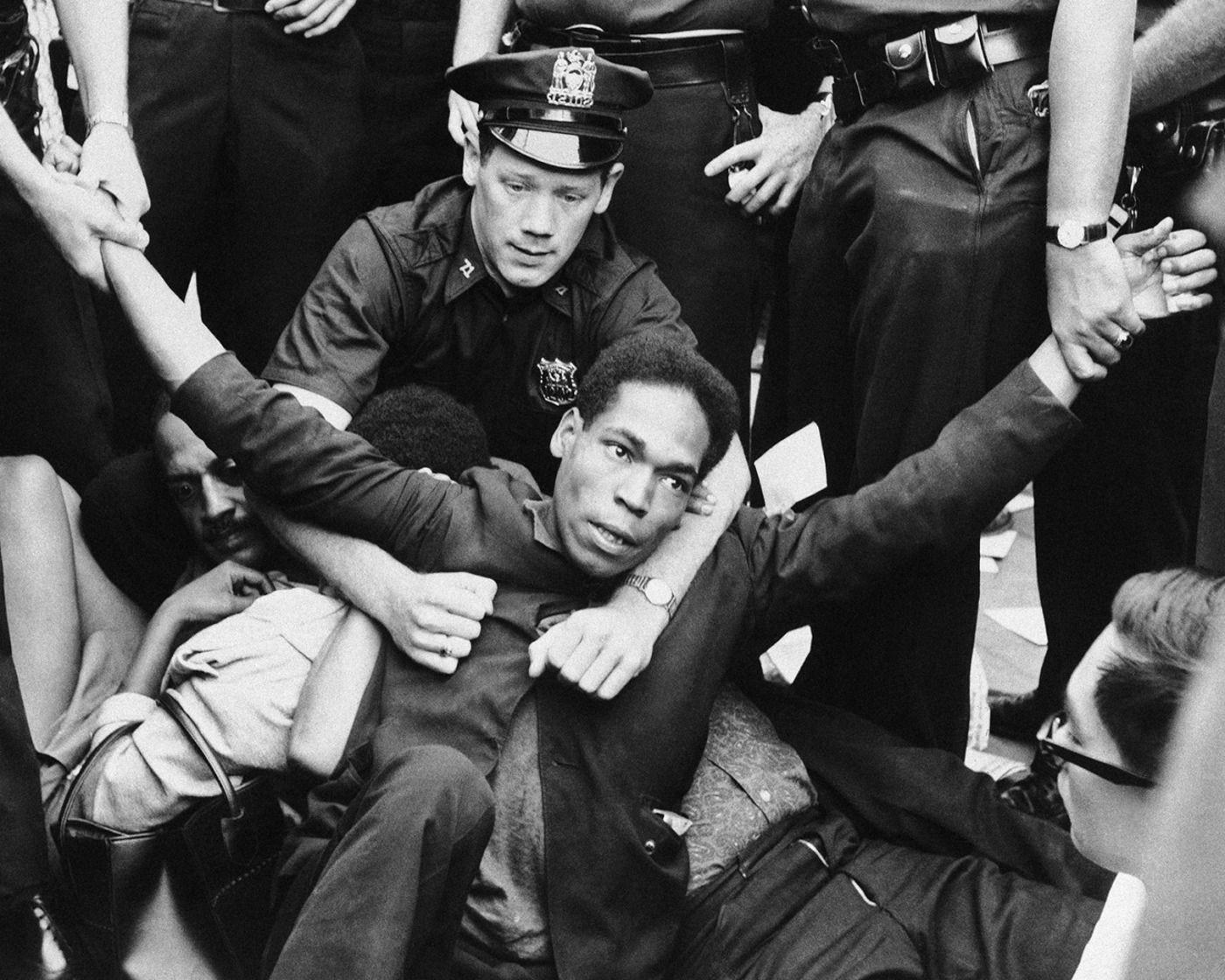

In New York City, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) led

the way, taking the streets in Harlem to demand that the construction industry

immediately hire qualified African-American construction workers. In the summer

of 1963, 150 demonstrators shut down work at the Harlem Hospital annex.

Protesters blocked entrances to the work site and forced police to remove them

from the site. Several scuffles broke out, forcing the head contractor to

suspend work for the day. The following day more protesters arrived and fears

of a riot eventually brought more than 300 police officers to the construction

site.

While tensions mounted at the in Harlem, the mayor at the

time, Robert F. Wagner attended a conference in Hawaii. In his absence, Paul

Screvane, the acting mayor, officially shut down the Harlem Hospital project.

Protesters cheered when they heard Screvane’s decision. Screvane suspended work

on the hospital until the mayor could confer with labor leaders and investigate

the demonstrators’ charges.

As a result, the Harlem Hospital demonstration made fighting

against racial discrimination in the building trades the most important civil

rights issue in New York City. Other demonstrations sprang up all over the

city, and a coalition of activists from different organizations began a

round-the-clock sit-in at the mayor’s and governor’s offices. Calling

themselves the ‘Joint Committee for Equality’ they demanded that New York

elected officials enforce the state’s anti-discrimination laws, especially in

the building trades.

In Brooklyn, CORE activists wanted to build on the momentum

generated by the Harlem Hospital demonstration. Their target was the Downstate

Medical Center construction project slated by the state of New York to upgrade

the Kings County Hospital complex with a new 350-bed teaching hospital and

renovations to the State University of New York (SUNY) medical school campus housed

on the same property. These projects were part of the $353 million earmarked by

the state in 1960 to expand the entire SUNY system by 1965. Upgrading the two

state medical schools was the main priority of State.

The massive, multi-million dollar, state-funded Downstate

Medical Center project seemed to be a win for everyone invested, the SUNY

system, Kings County, and the residents who wanted affordable medical school

training. But one group that criticized the construction project was

unemployed black construction workers,

especially those that lived in the black residential areas of north central

Brooklyn, which bordered the area which the Downstate project was located.

Brooklyn CORE activists found that except for a handful of

Carpenters’ Assistants, there were few black workers; the workforce for the

Downstate project was almost entirely white. Most of the workers came from

white areas of Brooklyn and Queens, but some commuted to the Downstate project

as far away as Long Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey. Yet black construction

workers could not attain jobs, although they lived just a quarter-mile from the

project.

Four leaders in Brooklyn CORE investigated the construction

site, and quickly realized that staging a demonstration at the Downstate

project would be difficult. The main work site was a seven-story medical facility

embedded in a sprawling complex four city blocks wide and one large city block

long. If Brooklyn CORE wanted to stage an effective protest and disrupt

construction at the project, they would need hundreds of participants. As a

result, its leaders sought support from other local civil rights organizations

and black churches.

Knowing that something needed to be done, Brooklyn CORE’s president

Oliver Leeds, contacted Warren Bunn, president of the Brooklyn chapter of the NAACP,

and John Parham, leader of the local Urban League chapter. In early July, the

three men went to the Downstate construction site to gather more data. Leeds,

Bunn, and Parham then took their complaints to leaders of local construction

unions and tried to convince them to recruit more black workers. The union

leaders’ responses were not pleasant. “They wouldn’t listen to us,” Leeds

recalled. “One of them almost threw us down the stairs.”

The three men went back to the Downstate project and planned

their demonstration strategy. They realized a large picket line in front of the

main entrance could effectively slow down the work site, and if enough people

sat down in front of the entrance, blocking trucks, they could repeat the

success of the Harlem protest. But Leeds knew Bunn and Parham could not rally enough

members to pull off that type of disruption. Demonstrators would have to

maintain the picket line from 7am to 4pm, five days a week. It would take

hundreds, if not thousands of people.

To find the people needed to successful picket the Downstate

project Oliver Leeds had the foresight to reach out to the black churches in

Brooklyn, several of which had over 1,000 members. But getting the ministers to

support a Brooklyn CORE project was its own struggle. For the most part, black

church leaders in Brooklyn held conservative views about civil disobedience.

Most prominent ministers did not want to risk their reputation by being

associated with Brooklyn CORE, and its protest, which tended to be

confrontational.

Most black ministers in Brooklyn at the time thought of

themselves as moderate power brokers, and had met with the mayor and governor on

several occasions, and some were appointed to government offices. The ministers

had traditionally used their influence over thousands of black voters as

leverage with elected officials. They felt they could lose their clout in City

Hall and in the Capital, if they participated in anything led by CORE.

But, many factors

changed the ministers hearts. According to Clarence Taylor, a historian, the Brooklyn

ministers inspired by the example of Martin Luther King, whose leadership in

the South motivated clergymen around the country to take direct action and

fight for social and political change. Confident they could get thousands of

their members to participate in the CORE protest at Downstate, they formed the ‘Ministers’

Committee for Job Opportunities’ and positioned themselves as the de facto

leaders of the campaign.

DIRECT ACTION at Downstate!

Impatient and bold, and not wanting to feel controlled by

the ministers, Brooklyn CORE members organized and began to picket the

Downstate construction site five days before the ministers arrived. On July 10th,

at 7am CORE amassed 30 members, along with their children, to block the entrance

to the work site, but failed to disrupt the site. This effort resulted in several

protesters being arrested when they sat down in front of an on-coming truck.

After getting news of the arrest at the Downstate

construction site, the Brooklyn ministers felt that their leadership could

control the picket line and keep the protesters from becoming too brash. On July 15th, they effectively took over as leaders of the Downstate campaign.

Still the demonstration attracted protesters who were neither interested in

following the minister’s directions nor willing to adhere to to the CORE principles

of nonviolence. These new protesters, more that Brooklyn CORE and the ministers’

moral authority and political power, proved to be instrumental in shaping the

outcome of the campaign.

For the most part, the ministers held rallies in their

church halls, raised bail money from members, and inspired congregants with

weekly sermons on the righteousness and justness of the Downstate construction

site protest.

Still, the Brooklyn CORE members were a significant force at

the picket line. Their experience during earlier campaigns made them much more

experienced than the ministers in working with the press and devising tactics

to disrupt the work site.

The ministers, on the other hand, were overly cautious when

it came to disrupting work at the site. Protective of their reputation, they

tried to choreograph their every move on the picket line, including the exact

day they would get arrested. The ministers planned to make their presence known

by giving interviews to reporters, and posing for pictures. They even sought to

control the demonstrators’ behaviors, a task that became more difficult as time

went on.

Media attention would be essential for the success of the

campaign, The CORE leaders and the ministers wanted photographers and

television cameras to capture images of demonstrators lying in front of trucks,

blocking entrances, singing freedom songs, and being carried away by police

officers, to rouse public support for increased employment opportunities for

African-American workers on publicly funded construction projects.

A rally held on Sunday, July 21st 1963, in Tompkins Park drew over 6,000

people. Reverend Sandy Ray declared that the Downstate campaign was a part of

the national struggle for civil rights and human dignity, “We are here in

response to the call of history,” he exclaimed. “There will be no turning back

until people in high in places correct the wrongs of the nation.” Reverend Dr.

Gardner Taylor shouted, “We’re ready!” he added, “We’re not going another step

and America is not going anywhere without us!””Revolution has come to Brooklyn!”

he shouted, “Whatever the cost we will set the nation straight!”

The Downstate hospital protest made history for the high number of people arrested for disruptive acts of civil disobedience. On July 22nd over 1,200 people attended the demonstration and over 200 were arrested – 143 were arrested on July 23rd – 84 on July 25th. This was the largest mass arrest of African-Americans in New York since 500 people were jailed during the Harlem riots of 1943.

Daily news coverage of dramatic, heroic acts of civil disobedience and record numbers of arrest made the atmosphere at Downstate a magnet for activists from all over the city. Malcolm X attended the protest daily, but never participated in the demonstration. Some Brooklyn CORE members approached X and invited him to join the protest, but he declined because CORE's the picket lines were inter-racial. Malcolm X was quoted as saying, "I'd be only to happy to walk with you just as soon as you get them devil off the line." But Malcolm X’s presence helped shape the evolution of Brooklyn CORE and it’s militant nature, and tactics.

.jpg)

While at the demonstration, Malcolm X caught the eye of a young Sonny Carson, who was drawn to the Downstate protest because of the militancy and dramatic tactics of Brooklyn CORE. A former street hustler and member of a gang called the Bishops, Carson was fresh out of prison when the Downstate protest began. Meeting Malcolm X that day turned him into a political activist. Malcolm X approached him, shook his hand, and, according to Carson, "looked at me and said, you look like you can get something done." That inspired the young man to direct his energies and leadership abilities towards black nationalist politics and militant activism.

But Brooklyn CORE members’ non-violent tactics, bold spirit,

and strong camaraderie, which kept the Downstate protest alive, also appealed

to a rowdier elements of the Brooklyn community, and out of work black

tradesmen that neither CORE nor the ministers could control.

"We Struggled in Vain"

After just three weeks of protesting, some on the Ministers’

Committee felt they might no longer be able to control people in the crowds,

which increasingly became restless with the lack of support from the mayor’s

office and the amount of arrest. Many ministers wanted to end the protest because

they felt the demonstration was taking up too much of their time and causing

them to neglect their churches.

The ministers officially became the leaders of the campaign,

when they jumped the gun, and issued the following demand: Governor

Rockefeller, Mayor Wagner, and Building Trades Council President Brennan had to

make the workforce on all publicly funded construction jobs at least 25%

African-American and Latino. Brennan denounced the 25% demand as blackmail; his

only concession was to establish a six-man panel to screen job applicants.

The ministers wanted to negotiate while they still had some

influence with elected officials. They were looking for a way out of the

campaign that allowed them to save face with their political contacts and

church members. An opportunity came at the end of July.

During the last few days of July, as the demonstration

threatened to fizzle without any gains, some protesters wanted to employ more

destructive and violent measures to gain politicians’ and labor leaders’

attention. On July 31st, the picket lines at the Downstate

construction site erupted into a near riot. Teenagers from local high schools

started a new technique that day. Ten of them locked arms and blocked a truck

until police asked them to disperse, which they did. Quickly, after they left,

another ten appeared in their place. The crowd of about one-hundred

demonstrators spilled into the streets, scuffled with the police, and one

protester kick a cop in the groin, sending him to the hospital.

The incident on July 31st was the breaking point for the ministers, and they quickly began to distance themselves from Brooklyn CORE and began to aid the police in cracking down on militant protesters.

On

August 6th the ministers’ committee met with Governor Rockefeller

and dropped its demand for the quota, and three hours later worked out a

compromise that ended the campaign.

In exchange for an immediate end to the demonstration, the

governor agreed to appoint a representative to monitor the construction

industry and report cases of discrimination to the State Commission on Human

Rights. Rockefeller also promised a special investigation into charges of

racial discrimination against blacks. Last, a recruitment program would be created

to place qualified African-American and Latinos in unions and apprenticeship

programs.

Except for the promised recruitment program, nothing new had

resulted from the Downstate protest, and subsequent talks. Moreover, there was

no guarantee that the Building Trades Council or the union, which retained

their power to discriminate without penalty, would support the governor and the

ministers’ apprenticeship program.

The ministers’ held a rally that evening and announced their

victory. They invited Olive Leeds to speak and publicly endorsed the

settlement, which he did. Twenty-five years later, Leeds regretted his

decision, calling it “the biggest mistake I’ve ever made in my life.”

Logistically, Leeds realized that the demonstration was over

without the ministers’ political influence and support. “Basically, I felt what

the hell, I can’t carry it by myself,” he said. “CORE can’t carry it. The NAACP

isn’t anywhere. Urban League’s got no troops and the ministers are pulling out.

What’s left? There’s nothing. So I agreed to go along.”

Members of Brooklyn CORE it was still possible to win minimum

hiring percentages or at least push for some immediate hires. They accused the

ministers of selling out just when tangible signs of victory seemed possible.

CORE wanted to the protest to continue. Leeds put the question to a vote, and

the decision was unanimous. But, Brooklyn CORE could not generate the necessary

numbers after the ministers abandoned the campaign.

In many ways, the Downstate protest might seem like a

failure. The promised apprenticeship program failed to produce many jobs. After

the settlement, Gilbert Banks, a black labor organizer remembered that the

unions and politicians “got a construction team to review 2,000 people who

applied for these jobs. There were 600 who could do anything they wanted:

electricians, plumbers, carpenters, steamfitters; all that stuff. The deputy

mayor got this committee together, and two years later, nobody was hired. So we

had struggled in vain.”

It is estimated that 5% of the U.S. work force, and 14 - 25%

of construction workers are illegal aliens. It's politically correct to call

them undocumented workers, but let's get real, they are undocumented because

they are here illegally.

The booming housing, and commercial construction industry over

the past few years has been cited as one reason so many illegal immigrants are

in construction , and you often hear,

"they are doing work that Americans don’t want to do." Bulls**t. If

you are a black tradesman, you know that's not true.

The debate over immigration reform found new life in 2016,

under a president who thoughtfully supports both increased border enforcement,

and deportations for those that have abused the system and have become felons.

From amnesty on the left to expulsion on the right - from

here on, it seems that anyone interested in speaking thoroughly on the matter

can no longer do so without discussing its impact on black America.

Although many factories have gone oversea, and have taken

millions of jobs with them, in the construction industry (and other industries

with a strong illegal work force, such as building maintenance and landscaping),

it is impossible to send the work to other countries, so instead of exporting the

work, workers are imported. Or rather, we look the other way when they work construction

projects.

This is subsequently overwhelming black tradesmen, and

killing their growth opportunities, since black tradesmen are often in direct

competition with illegal immigrants for construction jobs. “Black males are

more likely to experience competition from illegal immigrants,” Commissioner

Peter Kirsanow told The Daily Signal.

Kirsanow, an attorney in Cleveland and former member of the

National Labor Relations Board, said illegal immigration is both a short-term

and long-term problem for young black males.

“What happens is you eliminate the rungs on the ladder

because a sizable number of black men don’t have access to entry-level jobs,”

Kirsanow said. “It is not just the competition and the unemployment of blacks.

It also depresses the wage levels.”

As former Mexican President Vicente Fox infamously

declaring in 2006 that Mexican immigrants perform the jobs that “not even blacks want to do.”

Despite the former Mexican President assertion, illegal immigrants

worked heavily in the construction industry, an industry that employed hundreds

of thousands of blacks in 2018.

With some studies showing that black male unemployment is

being under reported, and is hovering around a staggering 17.6 percent, it

seems even less likely that immigrants are filling only those jobs that black

Americans don’t want to do. Just ask Delonta Spriggs, a 24-year-old black man

profiled in a Washington Post piece on joblessness, who pleaded, “Give me a

chance to show that I can work. Just give me a chance.”

Pew Research Center estimates that about 11.3 million people are currently living in the U.S. without authorization. More than half come from Mexico, and about 15 percent come from other parts of Latin America. These workers are doing work that U.S. citizens are willing and able to do. In the construction industry, they are hired under the table by unethical contractors who can charge much less for their work because they are undocumented, and their labor costs are much lower.

Contractors who follow the law, who document

all workers, pay all payroll taxes and worker's compensation insurance, are basically

being penalized for following the law.

In addition illegals are earning more than African-Americans. African Americans were paid a median household income of $36,000 in 2018. In the same year, the median household income for illegal immigrants was $45,000. Besides competing for work while simultaneously attempting to avoid drastically deflated paychecks and benefits, unemployed African-American tradesmen must also frequently combat racial discrimination, and high levels ethnic nepotism in the building trades.

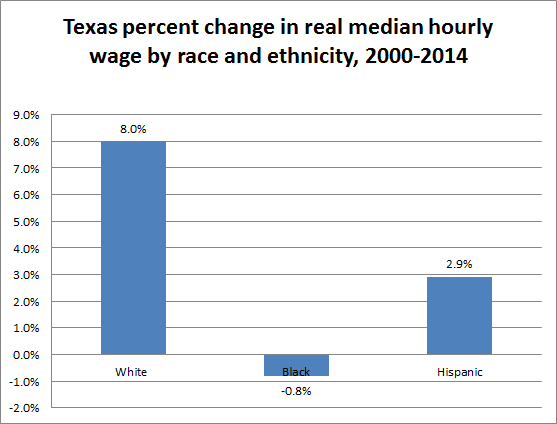

Texas Report

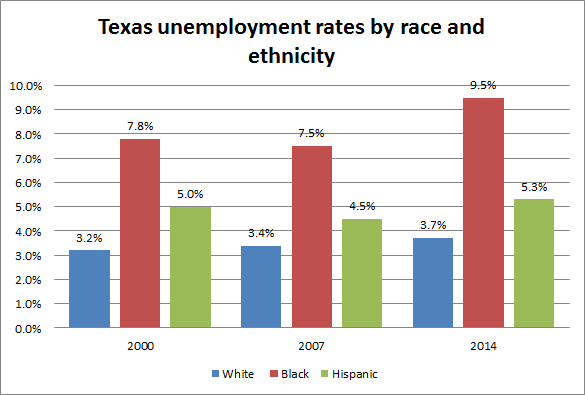

According to an alarming report by the University of Texas, half of the construction workers in Texas are undocumented. In a state were Black/African-American unemployment has consistently been nearly double that of white & Hispanic the report estimated that as many as 400,000 undocumented immigrants work in the Texas construction industry statewide.

Illegal immigrants are not

only willing to accept lower pay than their African-American workers,

but they are also less likely to receive safety training according to the

report. The report showed that 73% of illegal immigrant workers reported they

had not received basic safety training.

Texas black tradesmen have had it worst off as tradesmen of

other states, due to more than half of the state’s construction industry being

made up of illegal aliens. This claim also acknowledges wage fluctuations over

the years. Evidence shows Texas black workers in general have a higher

unemployment rate than fellow Texans and also being the lone group with the

lowest overall wages.

Reports provided by the Economic Policy Institute indicate

that median hourly wages of Texas whites and Hispanics increased 8 and 2.9

percent, respectively, from 2000 to 2014 while median hourly wages of black

Texans decreased 0.8 percent. When asked why black unemployment in Texas

appeared to be running higher than white and Hispanic unemployment and wages

much lower, Josh Bivens, director of research and policy, said this may be

because of discrimination in the labor market, according to politifacts.

Are trade unions

apart of the problem?

Construction unions over the pass few decades have focused

on keeping their members happy and employed, and have fought to keep lucrative

work building offices and highways instead of pouring money into recruiting

masses of new workers, such as black tradesmen & women. Nonunion shops on

the other hand, also looked over black workers, and instead made aggressive inroads

into home building, hiring thousands of illegal aliens who in most cases no

experience at all. The result: Today slightly more than 1 in 10 construction

workers are in a union, compared with 4 in 10 in the 1970s.

“What happened was, slowly, one contractor became nonunion …

and picked up a couple workers, and somebody told him about their Mexican

friends, and that was a model people adopted,” said Hart Keeble, the business

manager of the Reinforcing Ironworkers local 416, based in Southern California,

during an L.A. Times interview.

In fact, for more than 100 years, building trades unions refused

to hire black tradesmen & women. The Ironworkers local, like many building

trades unions, used to be an “old boys club,” Keeble said, where the unspoken

rule was to only let in people related to current union members.

Hire Black Youth

as Apprentice!

In the summer of 2005, when Las Vegas was going through a

construction boom, Keeble advertised in local papers to fill 150 union

apprenticeships over the course of a few months. After not being able to find

the workers he wanted, instead of advertising in an African-American newspaper

or publication he decided to advertise in a Spanish-language newspaper, as a

result he found all the workers he needed.

The Ironworkers union, whose members install the steel bars

and cables that form the skeleton of a building, used to take in 300

apprentices from high schools across California every summer. But in the summer

of 2016 they managed to only pull in 80. In most cases at-risk youth from

heavily populated African-American communities are not aware of these

opportunities, nor are they solicited to in any form.

According to Tom Brown, head of a San Diego based

engineering firm, 90% of his employees are “good old redneck Americans” and the

rest are immigrants.

Part of the reason black youth are also not running into the

trades is that employers aren’t eager to raise pay all that much. Even as home

building shot up from 2011 to 2018, hourly wages for construction workers rose

slower than average private-sector pay, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics

data, this can be directly attributed to illegal immigrants driving down wages

by excepting less pay for construction work.

A U.S. Civil Rights Commission study in 2010 determined

immigration had a disproportionate impact on black Americans, especially those

working in entry level positions, such as construction apprentice.

“About six in 10 adult black males have a high school

diploma or less, and black men are disproportionately employed in the

low-skilled labor market, where they are more likely to be in labor competition

with immigrants,” the commission report says.

The report continues:

“Illegal immigration

to the United States in recent decades has tended to depress both wages and

employment rates for low-skilled American citizens, a disproportionate number

of whom are black men. Expert economic opinions concerning the negative effects

range from modest to significant. Those panelists that found modest effects

overall nonetheless found significant effects in industry sectors such as

meatpacking and construction.”

Our Conclusion

“Some people are putting party preference over the needs of

their constituents,” say Commissioner Peter Kirsanow. “The [Congressional Black

Caucus] styles themselves as protecting and enhancing the interest of black

Americans. The problem is that black workers are being ignored. So, there is

another agenda at work.” Black Tradesmen U.S. agrees, whenever we speak on this

issue of the lack of black faces in the trades, and union apprenticeships, most

politicians and union officials just ignore the issue and kick the can, while recruiting

tons of illegals & DACA recipient’s instead of black tradesmen & women.

The construction industry has provided outstanding

opportunities for blue collar workers in the United States, but those benefits

has been largely restricted to white men and their families. After World War II, home

ownership along with Social Security, became one of the few entitlements that

allowed people to feel “American”. As numerous studies have shown, the racial

exclusivity of the post-World War II federal subsidies for home ownership,

combined with the lack of fair housing laws, disproportionately benefited white

families. The resulting level of wealth accumulation from the 1940’s to the

1960’s ensured that the middle class would remain predominantly white and

suburban.

Post World War II also marked a time when federal government

construction spending was at an apex, during which the building trade unions

used racially motivated tactics to restrict black workers from taking part in

the booming industry. Construction industry unionization was at its apex in

1940-1960, in fact, during this period half of all construction jobs were union

controlled, and in many cities outside of the Southern U.S. labor unions wielded

tremendous power. During the this time Federal & local laws were passed that required government

contractors to pay “prevailing wages”, which provided unions extraordinary

leverage to organize the construction industry. These laws and organizing

efforts ensured that the majority white construction labor poolwould receive a fair share of profits

from the construction boom.

Thus, although the construction industry literally paved the

way for the emergence of a postwar economy, black workers, tradesmen, and craftsmen remained largely

trapped in industrial jobs that provided lower wages, and very few

opportunities to move up the ranks into management. In fact, during the period

between 1940-1965 black unemployment increased rather than decreased, even

during the heyday of the postwar economic boom, because of the segregation of blacks into

low and semiskilled jobs. Due to de-industrialization in the inner-city black

workers were made vulnerable to layoffs, as factories were relocated to the

suburbs.

It was in this context that black activists of the 1960’s, in

mostly northern U.S. cities, frustrated with the glacial pace of post-World War

II racial liberalism and the slow pace of politically established civil rights

leaders, built a large blue-collar grassroots movement, to confront

institutionalized racism in the construction industry through large scale

protest. They were led by a combination of black youth, community activists,

and black construction workers who did not fit neatly into the standard civil

rights, black power, and labor movements. Their mobilizations gave everyday

people the means to put forward their own vision to confront the construction

industry and the so-called urban crisis.

Although, the black struggle for inclusion in the northern

building trades unions and the construction industry began long before the rise

of direct action protest during the 1960’s. During the first half of 20th

century, black tradesmen in the United States were restricted to the low-skill “trowel trades” of the construction industry. Even though black tradesmen

earned good wages hauling materials, excavating rock, and performing other

low-end construction work, this type of work, and even construction jobs that

required specialized skills, were rarely permanent and always physically taxing

and dangerous. When black laborers were no longer needed at a jobsite they were

laid off. With no union protection or job placement assistance, black tradesmen wandered

from site to site, city to city, in search of work, much like today. Black

tradesmen in the postwar era found it almost impossible to advance to positions

that required more skills and paid higher wages. Unlike many whites, they could

not use construction work to climb the economic and social ladder into the U.S.

middle class.

When black tradesmen attempted to join construction labor

unions it proved fruitless, and almost impossible. In New York City for

example, the industry was almost entirely white. Some union locals made no

attempt to cover up their exclusion of black tradesmen. Local 3 of the

electrical workers outright refused to admit black tradesmen. Plumbers Local 2

enforced racial exclusiveness by not issuing licenses to black tradesmen who

had gained experience or completed apprentice programs in other states. Sheet

Metal Workers Local 28 was strictly a father-son local with no black members at

all. The Carpenters union had more black members than other trades, but their union

halls segregated members as well. After World War 1, black carpenters were assigned

to Local 1888 in Harlem, and relegated black carpenters to jobs in Harlem only,

limiting the number of jobsites available to them. As a result, black

membership in Local 1888 fell from 440 carpenters in 1926 to only 65 in 1935.

In other instances’ some unions had no black members, or only a token number: Local 1 Plumbers 3,000 members total and only 9 blacks; Local 2 Plumbers and Steamfitters had 4,100 members total and only 16 blacks; Local 28 Sheet Metal Workers had no black tradesmen among its 3,300 members. In the 1960’s only the 42 Carpenters and Joiners locals had a sizable number of black members; out of 34,000 members, 5,000 were black/African-American. At a time when the construction industry was booming due to government-funded building projects, unions excluded black tradesmen from lucrative jobs, denied them access to apprenticeship programs, and barred them from advancement in one of the most promising labor markets for unskilled men with little or no specialized education.

White construction foremen usually hired black tradesmen

only when they were behind schedule. Even highly skilled black tradesmen would in

most cases find themselves hired to perform the worst jobs, and provided the

least pay, often in a temporary position as a “chipper”. Chippers operated a

pneumatic hammer that broke concrete, which was one of the most basic,

dangerous, and unhealthy jobs at a construction site. Men working as chippers for

long years did not live long; many developed ‘silicosis’ from breathing in dust

from the machines and spending hours in deep holes with little or no

ventilation.

Whenever black tradesmen would ask for permanent or more

skilled labor positions, foremen and unions would give them the run-around,

they’d say: ‘Do you have a union membership card/book?’ If the answer was no,

they’d say, ‘Go get a union membership card/book and we’ll give you a job.’

When the black tradesman would go to the union hall and ask to become a member,

they’d say, ‘Listen, if you get a job, we’ll grant you membership.’

As a result of this open and outright discrimination, black

tradesmen formed independent worker associations that served as parallel labor

organizations, not unlike those found among black craftsmen in other segregated

industries in the early 20th century. Over time black tradesmen

sought greater control of their work through state and local licensing to

become independent construction contractors.

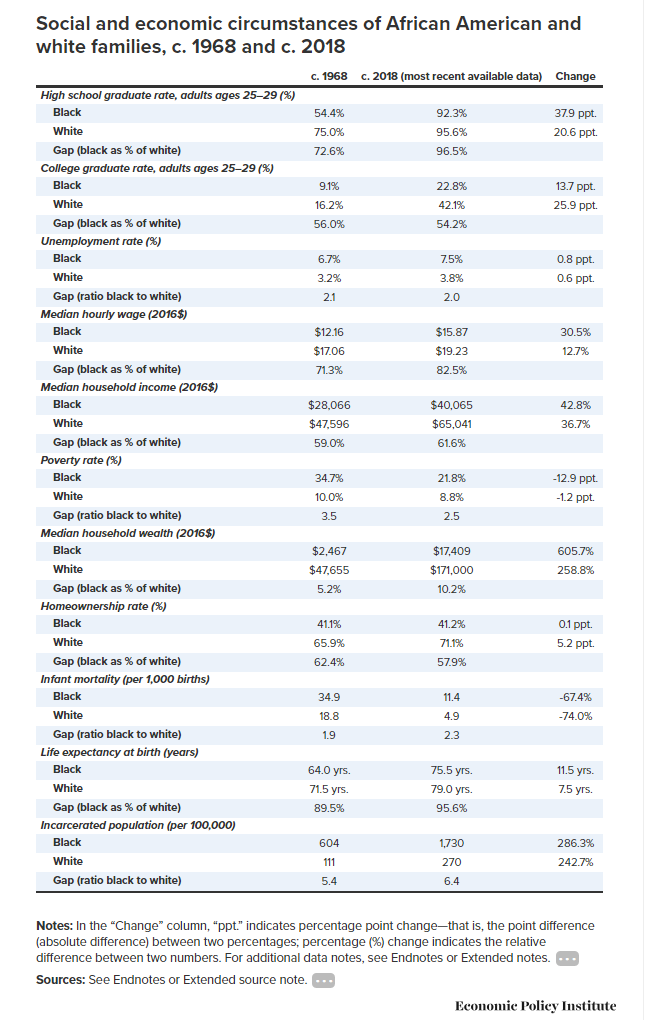

Economic Policy Institute - The year 1968 was a watershed in American history and black

America’s ongoing fight for equality. In April of that year, Martin Luther King

Jr. was assassinated in Memphis and riots broke out in cities around the

country. Rising against this tragedy, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 outlawing

housing discrimination was signed into law. Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised

their fists in a black power salute as they received their medals at the 1968

Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Arthur Ashe became the first African American

to win the U.S. Open singles title, and Shirley Chisholm became the first

African American woman elected to the House of Representatives.

The same year, the National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders, better known as the Kerner Commission, delivered a report to

President Johnson examining the causes of civil unrest in African American

communities. The report named “white racism”—leading to “pervasive

discrimination in employment, education and housing”—as the culprit, and the

report’s authors called for a commitment to “the realization of common

opportunities for all within a single [racially undivided] society.”1 The

Kerner Commission report pulled together a comprehensive array of data to

assess the specific economic and social inequities confronting African

Americans in 1968.

Where do we stand as a society today? In this brief report,

we compare the state of black workers and their families in 1968 with the

circumstances of their descendants today, 50 years after the Kerner report was released.

We find both good news and bad news. While African Americans are in many ways

better off in absolute terms than they were in 1968, they are still

disadvantaged in important ways relative to whites. In several important

respects, African Americans have actually lost ground relative to whites, and,

in a few cases, even relative to African Americans in 1968.

Following are some of the key findings:

· + African Americans today are much better educated than they were in 1968 but still lag behind whites in overall educational attainment. More than 90 percent of younger African Americans (ages 25 to 29) have graduated from high school, compared with just over half in 1968—which means they’ve nearly closed the gap with white high school graduation rates. They are also more than twice as likely to have a college degree as in 1968 but are still half as likely as young whites to have a college degree.

+ The substantial progress in educational attainment of

African Americans has been accompanied by significant absolute improvements in

wages, incomes, wealth, and health since 1968. But black workers still make

only 82.5 cents on every dollar earned by white workers, African Americans are

2.5 times as likely to be in poverty as whites, and the median white family has

almost 10 times as much wealth as the median black family.

+ With respect to homeownership, unemployment, and incarceration,

America has failed to deliver any progress for African Americans over the last

five decades. In these areas, their situation has either failed to improve

relative to whites or has worsened. In 2017 the black unemployment rate was 7.5

percent, up from 6.7 percent in 1968, and is still roughly twice the white

unemployment rate. In 2015, the black homeownership rate was just over 40

percent, virtually unchanged since 1968, and trailing a full 30 points behind

the white homeownership rate, which saw modest gains over the same period. And

the share of African Americans in prison or jail almost tripled between 1968

and 2016 and is currently more than six times the white incarceration rate.

Richmond, VA - For High school graduates, April means looking forward to

what comes next, which for many, means college. In April of last year, a

ceremony was held in Henrico County Virginia, to celebrate students who

selected careers as skilled tradesmen, over college. The county held it's

first-ever "Career and Technical Letter of Intent Signing Day,” to

celebrate those students and their imminent employment in the trades.

Instead of signing a letter of intent that’s usually geared

towards highly sought after student athletes, and high-academic performing students,

some graduating seniors signed declarations to prospective contractors, and

industrial employers, that resemble an offer letter.

"Henrico Schools’ Career and Technical Education

program decided that athletes weren’t the only ones who deserved to have their

hard work recognized as they look to the future," the county explained in

a post on its public Facebook page."Students and representatives of their

future employers both signed letters-of-intent outlining what students must do

before and during employment, what the employer will provide in pay and

training, and an estimate of the position’s value."

For their first signing day, Henrico County recognized 12

seniors as they signed letters of intent to work as machinists or apprentices

with local and national companies such as Rolls-Royce in their aeronautical

division, paving and construction firm Branscome Incorporated, Tolley Electric

Corporation, and Howell's Heating & Air.

According to Mac Beaton, director of Henrico County Public

Schools' Certified and Technical Education program, "We're always trying

to figure out how to address the skills gap when the general mentality of

parents is, I want my child to go to college; One way to do this is to help

them see the value of career and technical education," he said.

Tyler Campbell, 18, a senior at the Highland Springs Advanced

Career Education Center, signed a letter of intent to begin working for Branscome Inc., a contractor specializing in infrastructure, and commercial/residential

development, following his graduation in June. "Seeing how many people

showed up for the signing day, I could tell it was a big deal. I got really

excited," said Campbell, whose mom and sister were both in attendance.

"This is basically my dream job. To get it feels so good."

In the past, students from impoverished communities, or

working class neighborhoods were often pushed to go to college to achieve

better employment and upward social mobility. Over the last few decades, an

increase in college tuition costs has made student loan debt a reality for many

of those students from modest income homes. Now, millions of college graduates

face severe debt and job wages that are not sustainable in a post-2008 recession

economy.

Black American slave labor played the most important role in

constructing, and maintaining the historic Muscle shoals area in the U.S.

southern states. Many enslaved black men and women worked their entire lives, enslaved in the southern river region, and maintaining it’s

prosperity. In order to understand the history of the Muscle Shoals area, those

facets of that history having to do with the institution of ‘American chattel

slavery’ must be examined. This article seeks to explore the history of black