Ray's article

The voices of Black workers are being amplified as the

recent protest across the U.S. against state sponsored police murders of

unarmed black people and racial injustice have spilled into the labor

conversation, and the lack of black men earning a living wage in the

construction industry specifically.

As a result, construction firms and union halls across the

country are responding to this heightened awareness of employment

discrimination with statements calling for an end to racism in the construction

industry. Some firms have even introduced new programs to attract and retain

diverse team members, but not any specific to the black community.

Driving this wellspring of worker activism: pledges by

construction firms large and small that in the past have done little to balance

the economic scales for Black tradesmen or to eradicate toxic work environments

that have notoriously plagued the industry.

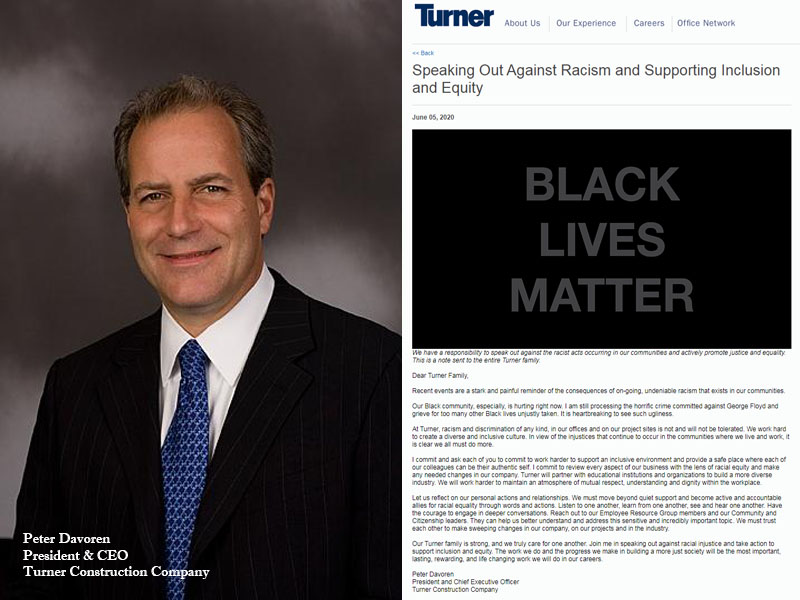

Turner Construction, one of the largest construction firms

in the U.S. has posted messages of support for diversity and eliminating racism in the industry on its websites and on social media.

“Our Black community, especially, is hurting right now… At Turner, racism and

discrimination of any kind, in our offices and on our project sites is not and

will not be tolerated. We work hard to create a diverse and inclusive culture.

In view of the injustices that continue to occur in the communities where we

live and work, it is clear we all must do more." wrote Turner CEO Peter

Davoren. CLICK THE LINK TO READ TURNER'S FULL LETTER

And In the home city of George Flyod, Daniel L. Johnson,

CEO, and David C. Mortenson, chairman, of Minneapolis-based Mortenson, signed a

statement from 29 Minnesota-based companies calling for an end to racial

inequities in the construction industry.

Hundreds of other construction firms, many of whom compete

for public works projects through the implementation of ‘Project Labor

Agreements’ (PLA), have also joined together to form outreach programs,

so-called sensitivity training, and hard hat stickers showing their pledge to

ensure their workplaces are free from racism, harassment, hazing and bullying.

Despite driving high-profile initiatives, these types of PR stunts are basically the same ole construction industry tough talk, without any bite. “The only jobs being made available to locals and minorities are the laborers jobs…The higher paying and higher skilled jobs are just not available.” President and CEO of the African American Chamber of Commerce of New Jersey, John Harmon.

John Harmon, also said,“From my personal experience and the research I have seen, PLAs have had no favorable impact on employment and contracts for minorities and women in construction…In most urban cities in New Jersey, the elected Democratic officials’ campaigns are overwhelmingly funded by unions who promote project labor agreements under the pretense that they will create jobs and contracts for minority and women. But in reality, the real winners are the elected official and the unions. No jobs, no contracts..."

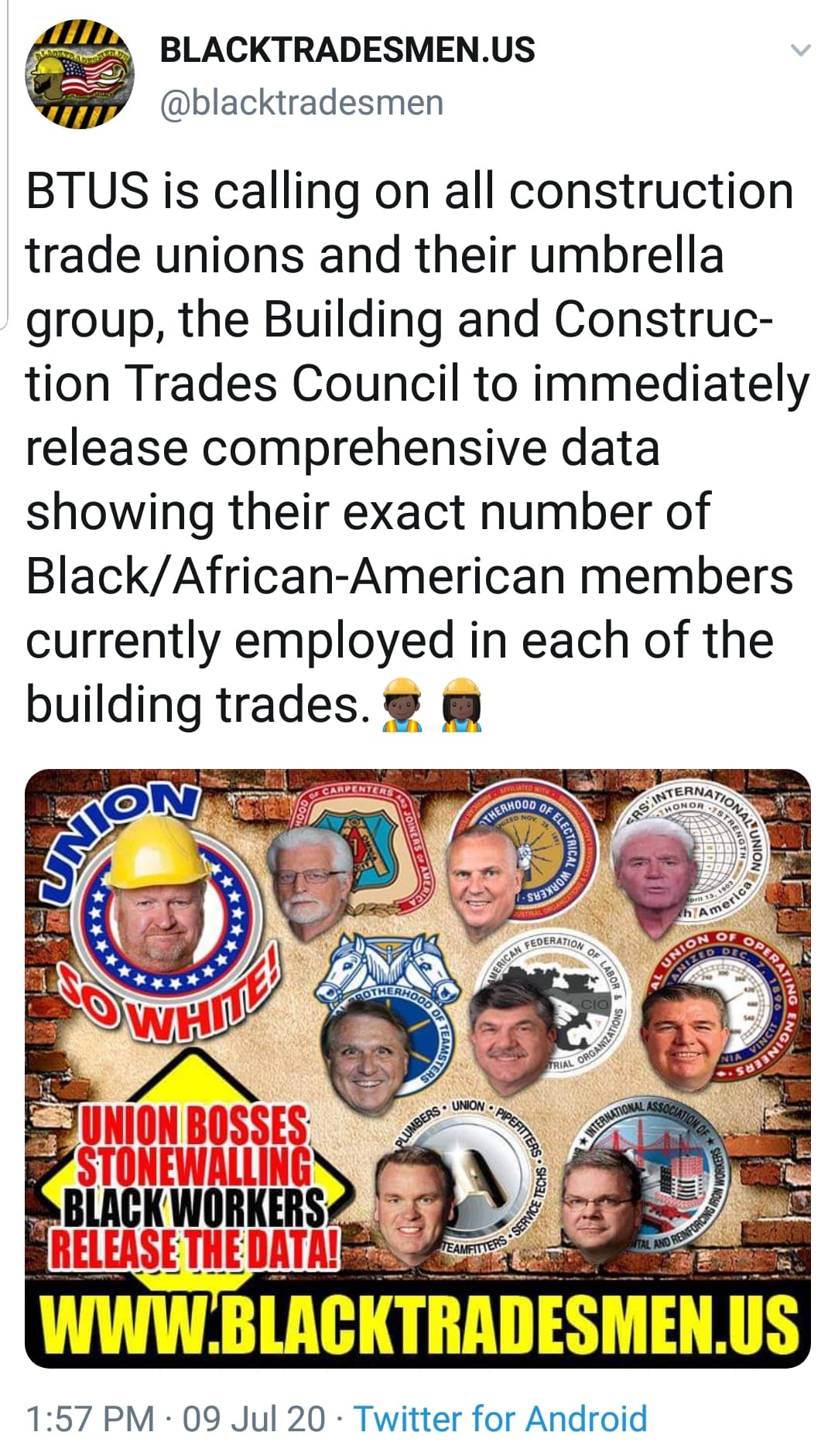

Being called out are construction firms and construction

labor unions that are publicly throwing their support behind the Black Lives

Matter movement , and other social causes while continuing the status quo of

not hiring black men, and guaranteeing them union protection.

At the same time, many construction firms have been

criticized for relegating workers, many of them black people, to low pay and

harsh working conditions.

“Black Job Matters was organized because outside developers come into our communities with promises to hire local contractors and local workers, but inevitably fail to keep their promises forcing Black and minority workers to watch on the sideline as others benefit instead,” said Elder Reginald Benjamin, founder of Black Jobs Matter “We are left out of the rewards of rebuilding our own communities.”

On June 25th the organization under the Black

Jobs Matter banner, were protesting Park East Construction Corp., a New York state Contractor, who has avoided

hiring local black workers from the local community. Black workers are

particularly angry because the $46 million put aside for the Park East

construction project comes from local taxes.

Black tradesmen and tradeswomen are not being treated with

proper dignity, and are not being promoted fairly in the field and in the

trailer. And in many cases there is no black leadership within the these

companies and or union halls at all, resulting in black tradespeople having no

place to express this type of discrimination without taking legal steps.

Industry leaders should affirm that they stand behind the

anti-discrimination policies, and will continue to operate in accordance with

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission [EEOC] guidelines and regulations,

or they may not be prepared to address the implication that has on their bottom

line.

Even as the drum beat of change is approaching, not one major construction firm in the U.S. has introduced any proposal that specifically addresses the lack of black workers in the craft trades, or any initiative to attract new black apprentice. Currently black tradesmen make up approximately only 3% of the craft trade industry, and only 6% of the construction industry that their forefathers built with skill for over 400 years.

Within the last few days the U.S. has witnessed several impromptu

and spontaneous labor strikes, known as ‘wildcat strikes,’ across it’s states

related to the recent COVID-19 pandemic. In Pittsburg a group of several hundred, mostly black union sanitation

workers, members of Teamsters Local 249, stopped work and went out on strike to

protest unsafe working conditions during the global health crisis.

The strike comes as momentum for strikes goes with

#GeneralStrike becoming the top trending topic on twitter in the United States.

Many are wondering if strikes like Pittsburgh’s sanitation

workers strike could be the beginning of a growing strike wave as Trump insists

that workers to return to work, although, Congress is out due to the health

risk of working.

Workers in Pittsburgh and elsewhere are resisting calls to

work in what most believe is unsafe conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We want better equipment, protective gear. We have no

masks, “one black union sanitation worker told WPXI.

“We want hazard pay. Hazard pay is very important,” the

worker told WPXI. “Why? Because we have high co-payments on insurance on any

type of bill. We risk our lives every time we grab a garbage bag”.

“Here we are at my job. Ain’t picking up no rub,” black

union sanitation worker Fitzroy Moss said in a Facebook live video. “The

rubbish is sitting there. That’s all they care about is picking up the garbage.

They don’t even care about our health.”

Despite the strike being illegal under state law, the

workers so far have made progress with Pittsburgh’s sanitation service. They

won a small victory as management allowed the workers to take the day off as

they meet with representatives of Teamsters Local 249 to address safety

concerns.

The strike comes as workers across the United States have

begun engaging in a series of bold, illegal wildcat strikes that before

COVID-19 pandemic would have been unthinkable.

Last week, non-union black poultry workers at Perdue Farms

in Georgia went out on a wildcat strike over unsafe conditions. Bus Drivers in

Birmingham went on strike demanding over lack of protections during COVID-19 as

well.

In Queens, New York, Amazon workers walked off the job last

week after a co-worker tested positive for COVID-19.

In Maine, naval shipyard workers at the Bath Iron Workers

went on a “sickout” strike in violation of federal law to protest being labeled

“essential workers” as shipyard workers.

Anger has grown in the labor movement about unsafe working conditions, especially after the announcement of the deaths and infections amongst construction workers and other blue collar professionals.

With workers fearing COVID-19, many workers are willing to

risk their jobs to save their lives.

Historically, General Strikes, like the one that began in

1919 after the influenza pandemic, begin in waves with large groups of workers

going out on strikes. As other groups of workers see the support that initial

wildcat strikes gain, they feel more confident of gaining the necessary

leverage to win a strike.

During the West Virginia Teachers’ strike, teachers in Logan and Mingo County began in December of 2017 going out on one or two-day rolling strikes. These smaller, county-wide rolling strikes demonstrated that not only could teachers defy state law in striking without consequences, but that they could win mass public support.

The smaller strikes helped show teachers in other counties

that they could take similar actions.

Many labor observers believe that the labor movement has

found itself unexpectedly in the early stages of a mass general strike wave in

the era of COVID-19.

“After health care workers, the working class and service

industry workers are on the front lines, navigating the fraught effort to

practice physical distancing,” says University of South Carolina-Upstate

Professor Colby King, the Pittsburgh-area, son of a union steelworker.

“Without widespread testing in our communities and without employers providing protective gear, it’s easy to see why these workers are reconsidering the risks they are willing to put themselves, their families, and their communities at to go to work,” says King.

In a letter to President Donald Trump, Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown

is calling for companies deemed essential during the cornavirus pandemic to pay

employees ‘hazard pay.'

“The next coronavirus-related legislative package considered by Congress should include a requirement for all companies deemed essential during the coronavirus pandemic to provide so-called “hazard pay,” or Pandemic Premium Pay, to their workers,” the letter read. “Pandemic Premium Pay should be equal to time and a half wages. It should be available to all workers, including part-time workers and independent contractors, for all of their hours worked, and it should be provided in their regular paychecks.”

Under Brown’s proposal the nation’s doctors, nurses, grocery

store workers, home health care workers, building cleaners, deliver workers,

letter carriers, transit workers, construction workers and others working in

essential industries would receive the pay.

The letter comes after a report from U.S. News & World

Report, where the magazine cites the President as saying he is considering

giving health care workers ‘hazard pay.'

Senator Brown proposed that the ‘hazard pay’ should be included as

part of the next coronavirus-related legislative package considered by

Congress. He also said the extra pay should be retroactive to the beginning of

the public health emergency through its conclusion.

But in Washington state, where the pandemic has burned

especially bright, Gov. Jay Inslee (D) has classified nearly all construction

as nonessential and urged workers to stay home. His orders allowed only for

construction projects to continue provided they “further a public purpose

related to a public entity,” which includes publicly financed low-income

housing and emergency repairs. Notably, football stadiums and condos for rich

people do not qualify.

One wonders why so few other state officials have followed his lead. As the outbreak continues to claim more lives, Inslee’s approach must become the rule, not the exception.

Building trade unions have been sounding the alarm on the hardships their members are already facing, and construction workers themselves have been speaking out and calling on elected officials to send them home.

In New York, the hashtags #StopConstruction and #NotAllConstructionIsEssential sent a desperate message to Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo (D) to halt work on frivolous projects. And some politicians are paying attention, including Cuomo, who called off all nonessential construction on last Friday.

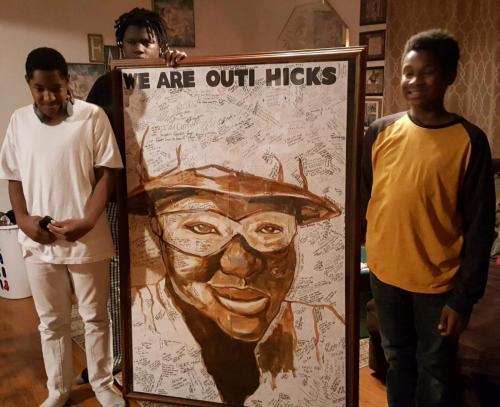

The charged killer of a 32-year-old union carpenter

apprentice and single mother of three at a Fresno, Calif. construction site

whose 2017 bludgeoning sparked fear and outrage among industry tradeswomen and

triggered a national movement to stop jobsite harassment and discrimination, has been sentenced in a

state superior court to 15 years to life in prison.

Aaron Lopez, a former part-time nonunion worker for a

scaffold erection firm at a biomass plant project with Outi Hicks who repeatedly

struck her with a heavy metal pipe, pleaded no contest to second-degree murder,

according to Fresno County court records.

The plea came in an agreement with prosecutors after he had

pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity to a first-degree murder charge in

2018.

Pictured Above - Outi Hicks three son's hold a poster signed by hundreds of tradespeople in honor of their mother. Outi was born in 1984 and was murdered in 2017 by her Co-worker. Outi was a resident of Fresno, California at the time of passing.

According to Engineering News Record ENR Lopez waived an arraignment and was denied probation, the

records showed

Gerald Schwab, attorney for Lopez, said at the Feb. 11 sentencing that the defendant had been treated for schizophrenia, PTSD and other mental health disorders and that it would have been difficult for prosecutors to prove premeditation in a case where Lopez killed Hicks for no apparent reason, according to a local TV news report.

Lopez had been harassing Hicks for days before the murder,

but she did not report the abuse to her union, Local 701 of the Carpenters'

union, or tell colleagues, according to

what some union members had told ENR.

According to Stephanie Basalyga's OP-ED for DJC Oregon -

Although she had been through some rough patches, including

a stint in prison, she found her way last year into a position as a carpenter’s

apprentice.

To her friends and family, it looked like Outi had found the

path that would allow her to build a solid future for herself and her children.

The feed of her Facebook account is filled with posts documenting her first

welding class and her first payment of carpenters’ union dues. Another, from

June, shows a smiling Outi wearing a fluorescent yellow vest, safety glasses

perched atop her head. The message: “At work! First job out here. Started from

bottom, now I’m here!”

But on Feb. 14, Outi’s journey – and her life – came to an end. While removing scaffolding on a project site, she and a co-worker reportedly became involved in a disagreement. Although details are still being investigated, preliminary reports indicate that other workers didn’t know there was anything wrong until they heard a commotion and rushed over to find 28-year-old Aaron Lopez hitting Outi with a [steel pipe].

Event Spurred

Intervention Push

Lopez expressed remorse during his sentencing and took

responsibility for his actions, said Kayla Franklin, a 23-year union carpenter

and Local 701 member who was in the courtroom. "He said the words,"

she said. Lopez will serve his sentence at the Wasco State Prison in Kern

County, Calif.

Hicks' murder triggered shock among construction tradeswomen

although many had often faced jobsite harassment, which was not always

reported, they said in social media posts.

All were "shaken to their absolute core the day that

happened,” said Vicki L. O’Leary, a

30-plus-year union ironworker veteran who now is the international union’s

general organizer for diversity and a high profile advocate for women in the

North American Building Trades Unions.

The murder boosted local and national efforts by women and

others in industry to stop jobsite harassment and promote stronger site worker

intervention, which includes the Be That One Guy program launched nationally by

the ironworkers' union, for which O'Leary was recognized in 2019 with ENR's

Award of Excellence.

"Outi is the reason this was and is being confronted.

My heart feels a little heavy thinking about her loss of life in such a

horrific way and how it is helping to change the industry," says O'Leary,

who adds she has presented details about the union's intervention program

recently to contractor and owner management groups, and at the American Bar

Association's Construction Law forum.

But O'Leary said there should be "no forgiveness for [Lopez's] behavior. Was he remorseful blow after blow after blow?"

California Law

California toughened anti-discrimination and anti-harassment

rules for construction apprenticeship program participants, including

instructors and contractors, in a bill signed by Gov. Jerry Brown in 2018 that

took effect in June 2019. It requires harassment prevention training, and set

policies and procedures for handling and resolving complaints and corrective

actions.

As of Jan. 1, the law's mandates now apply to all employers

in California with five or more employees.

"This incident is a dark example of the gender-based

violence experienced by women working in the construction industry," says

Melina Harris, a Seattle union carpenter and head of tradeswomen advocacy group

Sisters in the Building Trades, which, together with the carpenters' union,

raised funds for Hicks' funeral expenses and family support.

ARTICLE CREDITS Debra K. Rubin, ENR Editor-at-Large for Management, Business and Workforce

A black man from Oregon sued the city of West Linn alleging

that police officers unlawfully surveilled him at work and then falsely

arrested him in retaliation for having raised complaints with his employer

about racial discrimination.

Michael Fesser of Portland claimed in the suit, an amended

version of which was filed last month in U.S. District Court in Portland, that

the incident left him suffering from emotional distress and resulted in

economic damages. He sued the city and several members of the West Linn Police

Department for false arrest, malicious prosecution, defamation and invasion of

privacy.

West Linn police began investigating Fesser in February 2017

after Fesser raised concerns to his boss, Eric Benson, owner of A&B Towing,

that he was being racially discriminated against at work.

According to separate court documents, Fesser said the

discrimination included coworkers' calling him racial slurs. After he raised

his concerns, Benson contacted West Linn Police Chief Terry Timeus, his friend,

and persuaded to look into allegations that Fesser had stolen from the company,

according to the lawsuit.

The suit said the theft allegations were false and

unsubstantiated.

But with the approval of West Linn police Lt. Mike Stradley,

Detectives Tony Reeves and Mike Boyd used audio and video equipment to watch

Fesser while he was at work, according to the suit. The surveillance was

"conducted without a warrant or probable cause" and did not result in

any evidence that Fesser was stealing from his employer, the lawsuit stated.

"Sgt. Reeves and Sgt. Boyd unlawfully arrested, detained and interrogated Mr. Fesser in Portland, outside their jurisdiction, without probable cause," the suit said, adding that the two officers took Fesser's personal belongings, including papers expressing his concerns about racial discrimination at work.

Fesser spent about eight hours at the police station before

he was released on his own recognizance. He was later contacted by West Linn

police to come to the station to retrieve some of his belongings. While he was

there, officers informed Fesser that he had been fired from his job, according

to the lawsuit.

"The West Linn Defendants' surveillance, arrest,

incarceration and interrogation of Mr. Fesser without a warrant or probable cause

and their pursuit of baseless criminal charges against Mr. Fesser were racially

motivated, retaliatory, extra-jurisdictional and an egregious abuse of the

power with which the police are entrusted," the suit said.

According to the

lawsuit, criminal charges in the arrest weren't filed until after Fesser sued

his employer over his termination and for discrimination. The charges were

later dismissed.

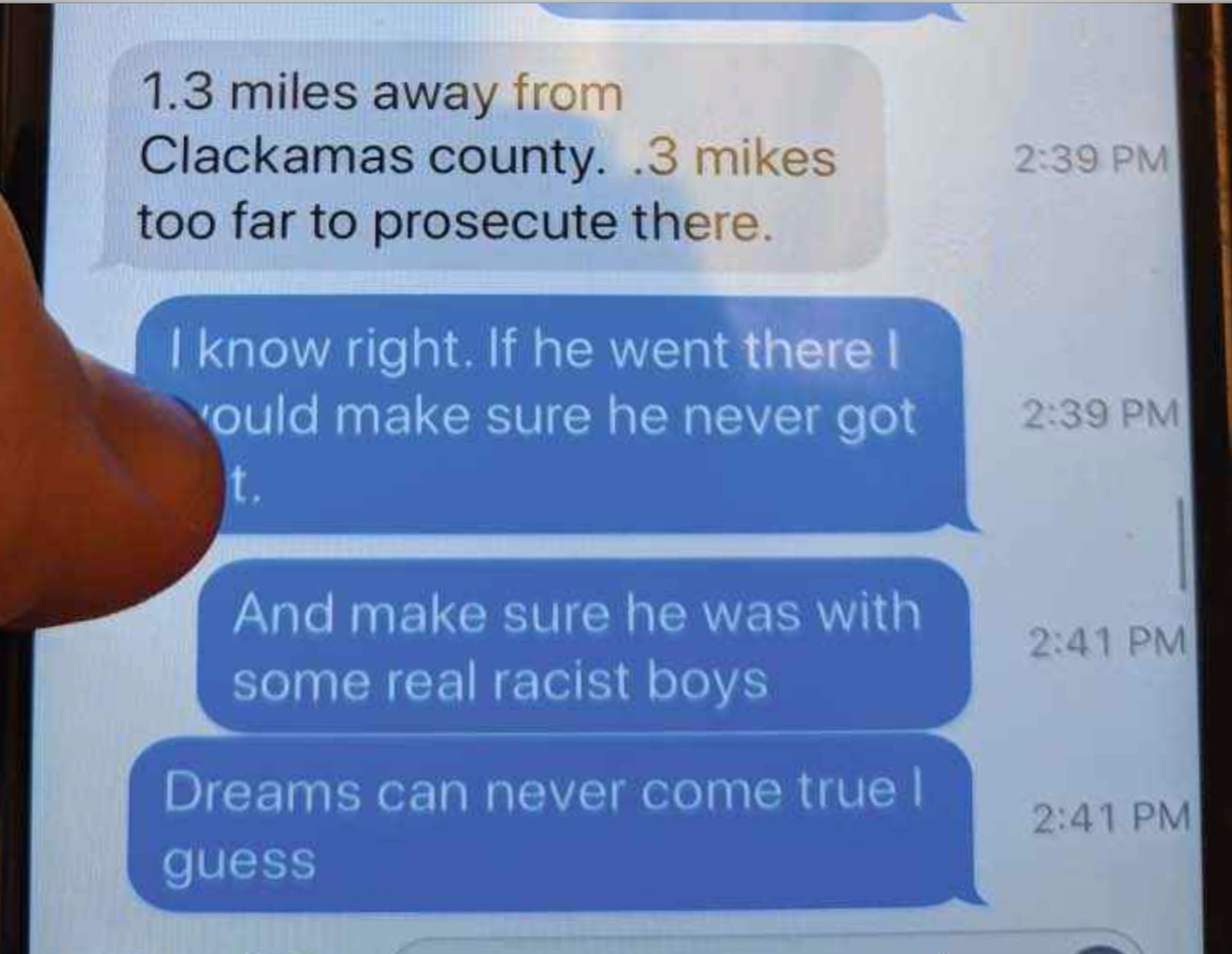

During the litigation in the lawsuit against his employer,

Fesser learned that the West Linn police investigation into the alleged theft

began as a favor to his former boss, according to the suit. Text messages

revealed during the legal proceedings showed that Reeves and Benson discussed

the investigation.

In one message, Reeves said Fesser should be arrested before

he went further with his racial discrimination complaint against his job so it

would not look like retaliation.

The City of West Linn

has since settled the lawsuit and agreed to pay Fesser $600,000. The lawsuit

against his employer was settled in March 2018 for $415,000.

Paul Buchanan,

Fesser's attorney, said his client is pleased that both cases have been

resolved.

"He is doing fine," Buchanan said. "This was not about money for him. This was about that they should not be allowed to do this."

According to Buchanan, the settlement against the police department could be the largest in the state for a wrongful arrest.

Timeus retired from the department in October 2017 following allegations that he drove drunk. You can find the complete West Linn Tidings story CLICK HERE

A&B Towing and the Portland Police Department did not immediately return requests for comments.

The West Linn Police Department said the settlement "is not an admission of liability."

"The City of West Linn and the West Linn Police Department do not tolerate any acts of discrimination or disparate treatment by its employees," the department said in a press release. "In 2018, when the allegations were first reported, an internal investigation was conducted and swift and appropriate disciplinary personnel action was taken."

Rico Washington was

sad. Oh, he was ecstatic, too. His company, Construction Works won the bid

to construct a new aircraft rescue firefighting station at the

Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport. The bid was the “lowest and

best” offer — in the language of the public bidding world — among four

companies vying for the $10.3 million project.

Washington’s

celebration was tempered, though, when he learned it was largest ever such

prime contractor bid awarded to an African American-owned firm on a Birmingham

construction project.

“Really?” he asked. “That’s

sad. Now, let’s fix it.”

Now, indeed.

NOW, when

Birmingham, Alabama’s largest city, is smack in the midst of an unprecedented

construction boom.

NOW, when more

than $300 million in taxpayer funds

will be spent to build a 42,000-seat stadium downtown and renovate outdated Legacy Arena.

NOW, when private

developers are on a giddy spending spree, too — sprinkling hundreds of millions

on the city’s core over the next three years like pixie dust, renovating and

restoring long-neglected downtown buildings and structures like Carraway Hospital ($327 million) and building

new ones like the Red Mountain Theater Company arts campus ($25 million).

NOW, when the

Birmingham Airport Authority expects to spend $117 million on capital improvements and $5 million on concessions over the next four years. “There will be

no end to the work we do for our customers,” airport CEO Ron Matthieu shared

last fall at a one-day conference for minority and women entrepreneurs. “It

will never stop.”

NOW, just after

ALDOT dropped $475 million to

replace the massive I-59-20 downtown overpass.

NOW, as the Housing Authority of Birmingham (HABD) prepares to spend $100 million in the next three years redeveloping five public housing communities.

NOW, after the University of Alabama at Birmingham spent more than $100 million on construction last year and estimates spending another $100 million in the next two to three years.

Do that math: Easily,

a cool billion could be spent on construction projects in Birmingham over the

next three years, alone.

Yet, this is our

shameful truth: Three decades after former mayor Richard Arrington launched the Birmingham Plan, a volunteer strategy to ensure minority-owned firms shared in

the city’s construction surge, which included an estimated $800 million in

commercial and public infrastructure spending between the late 1980s and early

1990s, few of Birmingham’s black- and women-owned construction firms are

prospering.

Some are doing well, no doubt. But truly prospering — as in,

capable of standing bid-to-bid with the city’s biggest construction companies?

Nah, not now.

BONDS, BIG BONDS,

NEEDED

One measure of a

construction company’s heft is its bonding capacity, the cost of a project that

a bonding company is willing to insure. To have, say, a $175 million bonding

capacity requires not only a lineage of successful large-scale projects but

also $26 million to $35 million in the bank — security representing 15-to-20

percent.

It is challenging to build those reserves without overseeing numerous big projects that produce positive cash flow, and it is a challenge to land those projects without a sizable bonding capacity.

Welcome to the

classic chicken-egg question.

Earlier this month, Brasfield & Gorrie, the city’s largest construction company, won the bid to build Protective Stadium, which is

projected to cost $179 million.

“No [minority-owned

firm in Birmingham] can build a $50 million project,” says Michael Bell,

executive director of the Birmingham Construction Industry Authority, an

oft-criticized entity that was created in 1980 in response to legal actions

taken against the Birmingham Plan. “It’s a sheer matter of cash flow. One could

not even submit a responsive bid. They can build a building like anyone; most

just don’t have the capacity to [bond more than] $5 to $7 million on a

project.”

“In many ways, the whole system has failed the minority

contractors,” says Tony Jones, founder of the Jones Group (The company

generated $2.5 million in revenue in 2019, according to Jones.) “The decision-makers, <Such as the Birmingham City Council, pictured above> who have largely been

minorities themselves in this town, for some reason are not [committed] to help

a minority company go from being a $100,000 revenue company to a $1.5 million

company. The train’s off the track.”

“A lot of disadvantaged [firms] are starving,” says L’Tryce Slade, founder of Slade Land Use, Environmental and Transportation LLC, <Pictured above> which

possesses a $3 million bonding capacity. “I have projects in Nashville, Dallas,

Atlanta, and Montgomery. I have projects in Birmingham but don’t feel the same

respect here. Why?"

Some black contractors,

simply and bluntly put, die from cash flow.

“We’re going to dump five hundred million into our city and

if we have nothing to show for it, shame on us,” says Brian Hamilton, managing

director of the A.G. Gaston Construction ($15 million aggregated bonding

capacity). “It’s not anyone’s fault. It’s all of our fault.”

If not now, then when? And why didn’t it happen before?

For a time, it did. Twice, in 1977 and 1989, the Birmingham City Council passed ordinances requiring minority firms get 10 percent participation in all public construction projects. Over time, minority firms reportedly gained almost a third of the contracts. But Arrington’s Plan was challenged in court, by the Alabama Associated General Contractors, and nullified by Crosson v Richmond, the 1989 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that declared the minority set-aside program for municipal contracts in Richmond, Va., unconstitutional.

The AAGC proposed the creation of the BCIA as an entity that

would certify minority firms, provide industry oversight and foster continued

growth. But it could seemingly do no

right.

Efforts by minority- and women-owned companies to crack the Birmingham construction industry’s granite code are further stunted by Alabama’s stifling bid law. It requires any public expenditure of at least $15,000— a ridiculously minuscule amount — to be awarded to the “lowest responsible bidder” in a sealed-bid process that does not even have to be advertised. (Professional services are excluded.)

Has anything changed in 30 years? There are really two answers: Somewhat and we’ll see.

“We have capable [minority-owned] firms here,” says Clinton

Woods, owner of Prescott Contracting and the District 1 City Councilman. “There

are a lot of good things happening, but we’ve got to get better. Our [city’s]

role is to build capacity, awareness, and opportunity.”

Protective Stadium and the long-overdue renovation of Legacy Arena are a “unique” opportunity for public spending to break from its tainted history and boost the trajectory of black- and women-owned construction firms in the city, says BJCC Executive Director and CEO Tad Snider. “[They’re] not going to come around every 10 years,” he says. “So how do we refine and enhance the process and do what needs to be done to prepare businesses to grow?”

The BJCC strives for

30% inclusion by minority- and women-owned companies, Snider says, and is

“clear” about the goal with bid-winning firms. “We try to find partners that

share that commitment.”

For accountability, the BJCC engaged Selena Dickerson, founder/owner of Sarcor, LLC, a black (and female)-owned engineering firm, to track dollars spent on the projects with black-and women-owned firms. Each month, she creates a detailed — to the penny — report.

Prime contractors are required to submit the amount they

spend with diverse subcontractors, and those figures are confirmed with the

businesses.

Through December 2019: 28% of spending on stadium excavation was made with minority- and women-owned firms, including $481,714.75 spent with black-owned Championship Enterprises (asphalt milling, demolition, hauling, and erosion control).Spending for professional services (architecture, engineering and construction management) for the stadium totaled $2,778,214.25 with eight diverse firms, representing 21% of overall dollars spent.

For the Legacy Arena renovation (contracting bids open

February 20), $3,898,981.17 was spent with 15 minority- or women-owned firms —

28% of the total.

Snider <Pictured above> presented the update at a City Council Committee of the Whole meeting. Councilor Steven Hoyt has long been a vocal critic of the BJCC’s historic dearth of spending with minority- and women-owned firms. “Well,” he said to Snider, “you have shut me up.”

Outside of City Hall,

particularly among minority-owned firms, there is frustration with Birmingham’s

level of spending of taxpayer dollars with black- and women-owned enterprises.

(The city’s five-year Capital Improvement Budget totals more than $350 million

for FY19 through FY23.

“I don’t depend on the city for anything,” says Tony Jones <Pictured ABOVE>. “I don’t even

bid on their jobs. We go a whole other route. We go to the private sector and

work with those who will work with us. I don’t care what color they are.”

Inside City Hall,

there is frustration, too, with the state bid law constraints.

“There is a spirit and desire to do more, but we can’t ignore [it],” says Tene Dolphin, deputy director of diversity and inclusion in the mayor’s office. “We can’t give preference points or have the appearance of awarding one contract over another based on race or gender.”

“We just have to focus,”says Dolphin <Pictured above>, who once served as senior deputy director of Washington D.C.’s Department of Small and Local Business and worked in the U.S. Department of Commerce.

“We have to challenge [general contractors] and we want to. We also need all of our service providers to take further steps in growing companies and building capacities – from the back office to bookkeeping, to funding and bonding to knowing how to bid on projects.”

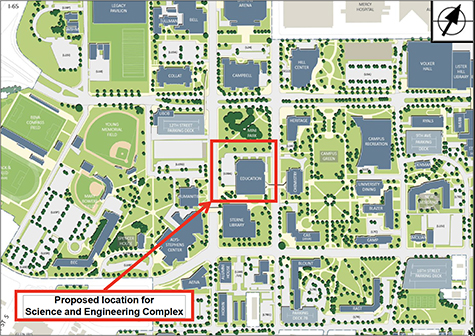

This year, UAB will begin construction on the science and engineering complex, athletic support building for baseball and softball and renovation of the Boshell building. The university must abide by the state bid law but, through its Small Business Inclusion effort, strives to “partner with diverse business enterprises to train and prepare the businesses in our community, ultimately supporting the community involvement and economic development pillars of UAB’s strategic plan,” according to a UAB spokesperson. “Our bids stay within state laws, while representing UAB’s culture and shared values.”

Last year, UAB spent

more than $15 million with MBEs, according to Greg Parsons, associate vice

president and chief facilities officer.

HABD and the Airport Authority have bid standards to assure high-quality standards are met, but since they’re largely funded with federal, not with state or local dollars, they’re not handcuffed by the restrictive state law. Thus, the agencies can be more intentional about engaging women- and minority-owned firms.

Last fall, the HABD approved an agreement with Southside Development Company, a consortium of six firms to oversee the $26 million

development of the Southtown public housing community. The consortium includes

construction heavyweights Corporate Realty and B&S, as well as two black-owned firms, Gaston and The Benoit Group, based in

Atlanta.

“I am committed to ensuring that minority- and women-owned businesses are operating on a level playing field,” says Cardell Davis, who chairs the HABD board of commissioners <Pictured above, center>. “Our task is to create policies that allow for equal opportunities and to make sure that those policies are being implemented.”

Rico Washington, VP Operations, Construction Works <Pictured above>

Construction Works, which has begun construction on the airport fire station, has a bonding capacity of $20 million for a single project, $50 million in aggregate, according to Washington. The company is based in Georgia, although it is opening a Birmingham office. Company founder, Cedric Walker, is a native of Tuscaloosa; Washington grew up in Titusville.

The company has a strong portfolio of projects, including several airport projects. The company constructed a $20 million equipment facility for Delta Airlines at Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport under Dunn Works, its unique joint venture with J.E. Dunn Construction, a 90-year-old company with $3.6 billion in revenue and 20 offices nationwide.

There is still

lingering antipathy with the private sector due in some circles to its legacy

of obstinacy towards black- and women-owned businesses. Though it’s seemingly

fading with more large firms appearing to be using DBEs for significant

subcontracting roles.

Brasfield

& Gorrie, the city’s largest construction company, has gone even

further. Last September, with the blessing of CEO Jim Gorrie <Pictured above>, son of founder

Miller Gorrie, the company launched EQUIP to “deliver education and

networking opportunities” to minority- and women-owned enterprises, as well as

“a forum to engage in industry best practices.”

For Jones Group,

LLC, EQUIP has been much more.

Samuetta Drew (left),

Sr. Executive Director of Security Operations, and founder Tony Jones (right)

of Jones Group, LLC, with Brasfield & Gorrie project manager Robert Robison

(center)

The brothers (along with Ronald’s wife, Roxie, who quit her

job with the U.S. Department of Commerce to join them) launched as a staffing

company in Mobile doing cleanup for the deadly oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico

that year. They later moved to Birmingham and handled clean up after the deadly

tornadoes that hit the city in 2011.

With a desire to move into contracting, they installed flooring for Lowe’s (“They did not have any black-owned companies installing floors,” says Tony Jones) then created three divisions: flooring/sheetrock, framing, and ceilings.

They began remodeling homes and churches then, in late 2017, received a call from B&G to see it was interested in quoting a job for them. “Of course, we said yes,” Tony said.

The company is now

acting as a general contractor in the area of utilities—under Jones Group

Utilities—and is striving to be general contractors in construction.

“We try to survive on our performance,” Tony Jones adds. “Independent of race, creed or color, we want to perform. We want you to think of the Jones Group as a good company. Sure, we’re a minority-owned company but we want the first thing you think to be that they are a good company.”

DON’T LOSE MOMENTUM!!!

Washington and others

firmly believe the key to capitalizing on this time of unprecedented growth,

beyond continued education on business operations, is a further collaboration

among minority- and women-owned firms—combining resources, for instance, to bid

for bigger projects.

“Being selfless and

open to collaboration,” he says. “I can compete against you and still share

stuff with you. I know my limitations; I can’t do every job. Together, though,

we can do more. We have to show them.”

If not now, when? Or ever? We’ll see.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY WRITTEN BY ROY S. JOHNSON FOR AL.COM

Sears is demonstrating that it’s perhaps the saddest and

most prominent victim of the so-called ‘retail apocalypse’ sweeping across the

U.S. Sears, which is owned by Transform

Holdco, is set to close 51 total stores by

February 2020, according to a press release from the parent company. And as

tradesmen we are horrified, the very thought of losing the immediate gratification from trying on your first pair of Die-Hard boots, or purchasing that classic ruby

red Craftsman speed square, is sending chills down the backs of construction pros everywhere.

Our beloved Sears narrowly escaped complete shut-down after filing for bankruptcy in the fall of 2018. Since then, more than 250 stores have closed their doors. In the past 15 years Sears and it's partner Kmart have closed more than 3,500 stores and cut about 250,000 jobs, according to USA Today.

After this new round of closings and previously announced closings, this once grand jewel of the retail industry that traces its roots back 133 years will have just 182 stores nationwide.

CLICK LINK FOR LIST OF SEARS STORES CLOSING IN 2020

BUT NOW WHAT? WHERE WILL WE BUY OUR BELOVED BRANDS,

DIE-HARD, CRAFTSMAN, AND THE WIDE VARIETIES OF TIMBERLAND PRO, AND DICKIES???

First sold in 1927, Craftsman was the flagship brand in the

Sears tool section. For 90 years this esteemed brand name was synonymous with

quality manufacturing, affordable pricing, and an almost legendary lifetime

warranty. These three traits meant that it was almost impossible to find an

American garage or workshop that didn’t have at least some Craftsman tools

hanging on the walls, familyhandyman.com

"After careful review of where we are today, we believe

the right course for the company is to accelerate the expansion of our smaller

store formats which includes opening additional Home & Life stores and

adding several hundred Sears Hometown stores after the Sears Hometown and

Outlet transaction closes," the company said in a press release.

So according to release, the new closings do not affect the company's recently acquired Sears Hometown stores, which specialize in home appliances, equipment and tools from the Sears line of products like Whirlpool, Craftsman, Kenmore and Die Hard. Our beloved brands, but also other brands as well.

According to theadvocate.com:

The Hometown and Outlet stores have been insulated somewhat from Sears’ struggles in recent years. The Hometown and Outlet stores, however, have struggled as many retailers nationwide have had to downsize. The company reported a net loss of $3 million in the fourth quarter of 2018 compared to the previous year and $41.6 million for the year compared to 2017.

Last month the Hometown and Outlet Stores rejected an offer

from a company affiliated with the hedge fund controlled by former Sears CEO

Eddie Lampert to buy all the remaining Sears Hometown stock not already owned

by the fund. Lampert, a CEO who was once kidnapped and held for ransom, according to some reports, is interested in closing the

Hometown stores.

"In many cases, the smaller towns or less affluent

areas of the country where there's not much hustle and bustle or competition

are where people still want to go someplace to shop,” said Jake Dollarhide, a

Tulsa, Oklahoma-based investment adviser and retail analyst. “They don't want

to pay for Amazon Prime or delivery charges and instead want to go get the

products they need now at stores they know nearby."

BLACKTRADESMEN.US WILL FOREVER LOVE DIE HARD BOOTS!!! XOXO

We’ve reported the fact before that black construction union

members earn less on average than white union members. The unionized

construction workers in New York City specifically, earn 20% less on average

than their white co-workers performing the same trade. Through the

implementation of racial discriminatory hiring practices and Jim Crow ere

pre-apprenticeship programs New York City’s construction labor unions have

effectively maintained a 91% white male membership.

This is the story of Averil C. Morrison, a black tradeswoman,

who along with 4 other union operating engineers ( one black tradeswoman, 2 black

tradesmen, and 1 Hispanic tradeswoman) sued the International Union of

Operating Engineers Local 14-B—a AFL-CIO member union—for racial discrimination.

AVERIL MORRISON IN HER OWN WORDS

“As one of fewer than 20 minority females in the

1,600-member International Union of Operating Engineers Local 14-14B — one of

the city's construction unions — I know first-hand that our mostly white

membership book is not a coincidence. Rather, from my perspective, it appears

to be a direct consequence of the union leadership's actions to limit access

and opportunity for skilled workers who aren't white males.

In New York City, the Operating Engineers is considered an

elite construction union. Members operate bulldozers, backhoes, cranes and

other heavy machinery, and they're paid well for their work. Hourly pay and

benefit rates range from roughly $70 an hour for unskilled jobs to $120 an hour

for skilled positions. (Work that's done on weekends, holidays or overtime is

paid at double the base hourly rate.)

These are the jobs that helped build the middle class, and

it's easy to understand why workers of all racial backgrounds aspire to them.

Unfortunately, New York City's construction unions have historically kept these

opportunities from people of color. You can still find on city government's

website a copy of "Building Barriers," a report on racial

discrimination in the construction industry that was released in 1993.

The city's unions argue that they've improved since then,

and certainly they have. Some of these improvements were court-ordered. But

progress remains painfully slow. At the end of 1988, 9% of Local 14-14B's

membership was non-white; today that figure is roughly unchanged, in a city

that's 35% black and 27% Hispanic.

On a personal level, it's clear the problems that a black

woman like myself faced then still exist today.

It starts with the apprenticeship program, the pathway

through which a worker is supposed to learn the skills of their trade and move

on to full union membership. In my class, which was composed entirely of

minorities, we spent our time either sitting in the classroom or watching other

people work on equipment; I didn't receive on-the-job training until my second

year. But there's a loophole: If you're sponsored or referred by an existing

member, you can bypass the apprenticeship program and earn higher journeyman

wages on the job as you learn your skill.

Not surprisingly, friends and family of the existing white

membership are frequently beneficiaries of this loophole, while people of color

languish in an apprenticeship program with minimal pay and opportunity. It took

me nearly four years to "get my book" — a term used to describe full

union membership — and even then, it was only through persistent communication

with the gentleman running the training program. Other minorities aren't so

lucky.

Unions are supposed to create a level playing field for

workers, nowhere more so than in the hiring hall where work is assigned. The

hall opens at 6 a.m. every morning, and available jobs on any given day should

be distributed on a first-come, first-serve basis. Access to the longer-lasting

and better-paying jobs is supposed be a matter of luck. In reality, rising

early and having luck matter less than who you know and what color your skin

is.

I should know. I've spent too many mornings waking up at

2:30 a.m., commuting to the hiring hall, and standing outside for two hours

only to receive a low-paying job that lasts for a day or two — or no work at

all. Meanwhile, the good-paying jobs on long-term construction projects are

assigned far in advance, when the union's business agent parcels them out

overwhelmingly to connected white males.

In 2012, fed up with being treated as second-class citizens,

a few of my colleagues and I filed a discrimination complaint against our

union {The trial begin spring 2016}. We filed the complaint not just for

ourselves, but on behalf of other minorities who are skilled tradespeople but

are being denied the opportunity for good work on account of their skin color.

We're not trying to punish the union. We're trying to improve it.” - Averil Morrison, New York Daily News

According to Laborpains.org court findings revealed, the union (Local-14b) allegedly

allows its predominately white membership to refer new prospective members (who

are predominately white) as full journeymen, while requiring prospective

members without connections (who are more non-white) to do lower-paid

apprenticeships. The plaintiff union members allege that the largely white

referred new members get to skip apprenticeship even if they do not have “any

qualifications other than being sponsored by an existing White member.”

A brief review of Local 14-B’s wage scale shows just how big

a favor skipping apprenticeship all together can be. According to the 2015-16

apprentice wage scale, first-year apprentices are paid $29.25 per hour (40% of

the Pile Driver rate). By the end of a three-year apprenticeship, the wage

rises to 60% of the Pile Driver rate ($43.87/hour). Meanwhile, a full-member journeyman Pile

Driver is making $73.12 per hour.

There are further allegations of the union rigging job

placements in favor of white members. Using its control of the hiring hall

system of job referrals, Local 14-B allegedly manipulates the hiring hall so

that white members get jobs that last longer (which assures white members of

higher earnings and less time unemployed). Even more egregious, Local 14-B’s

absolute discretion for assigning “master mechanics” (essentially shop stewards)

ensures a racial wage gap, as master mechanics who are appointed are allegedly

“almost never” non-white. Master mechanics allegedly “can work virtually as

much double time as he desires” and “easily earn several hundred thousand

dollars a year.”

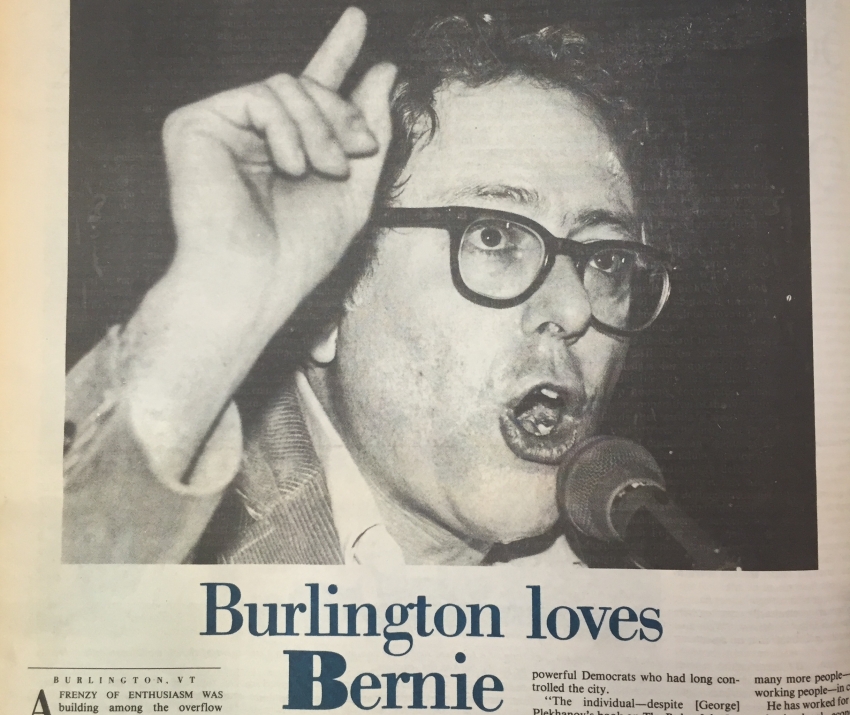

In the mid 1970’s Bernie Sanders was the chairman of the Liberty

Union Party, which was a Vermont spinoff group from the Socialist People’s

Party. According to interviews obtained by The Daily Beast and other news

sources, as chairman of this self-described “radical political party” Sanders, repeatedly

compared Vermont white workers to enslaved black people.

In one 1976 conversation, Sanders told a local newspaper that the sale of a privately held mining company by its founders, a company that employed mostly white workers, reminded him of “the days of slavery, when black people were sold to different owners without their consent,” and compared the service economy to chattel slavery.

Reports also show that in a 1977 interview Sanders went on

to compare the state of Vermont’s majority all-white population to black

slaves, due to the fact that the majority of white’s working in the state were

working in the low paying service industry. In the interview Sanders says “Basically,

today, Vermont workers remain slaves in many, many ways,” he went on to say, “The

problem comes when we end up with an entire state of people trained to wait on

other people.”

Lately, Sanders arrogance toward the history of American

chattel slavery, has been very bold, contradictory, and completely absent when

it comes to addressing the plight that black Americans are burdened with as a

result of the atrocity their ancestors endured.

Today, the black American descendants of chattel slavery

account for a disproportionate amount of low-paying service jobs, such as

cashiers, call-center operators, food service workers, security guards, and

temp workers across the states, as compared

to higher status jobs paying a living wage, such as the one’s Sanders fought for in

Vermont.

Other occupations such as customer service reps and front

line sales people are also expected to take heavy job loses as technology is

expected to substitute or completely take over functions that over 25% of black

workers traditionally perform.

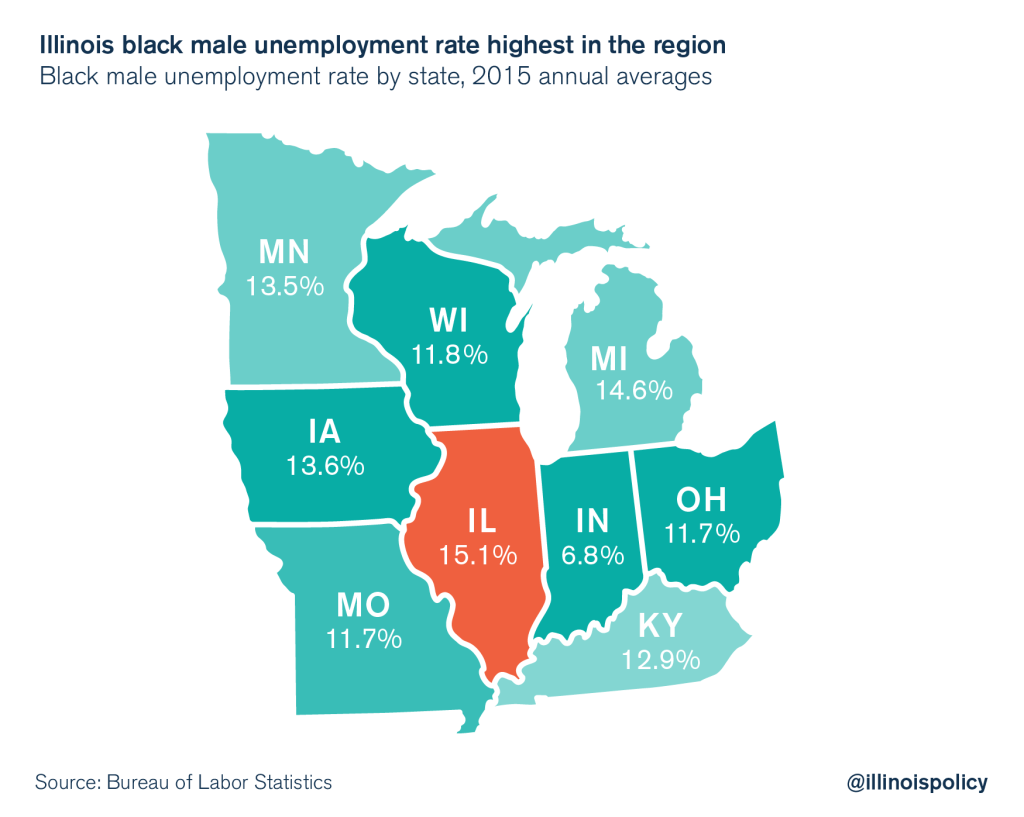

As the overall labor force participation rate for black workers, like the rate for all race groups, is projected to decline by the year 2026, no single gender/race group is expected to decline more significantly over the next 8 year than the rate for black men in the U.S. labor force.

Bernie Sanders compelling ignorance of this major issue of unemployment and underemployment plaguing specifically black male descendants of chattel slavery is causing an uneven accord among black voters, who believe that Sanders is playing dumb on the issues, or is just plain out spearheading the demise of black male descendants by completely ignoring their issues.

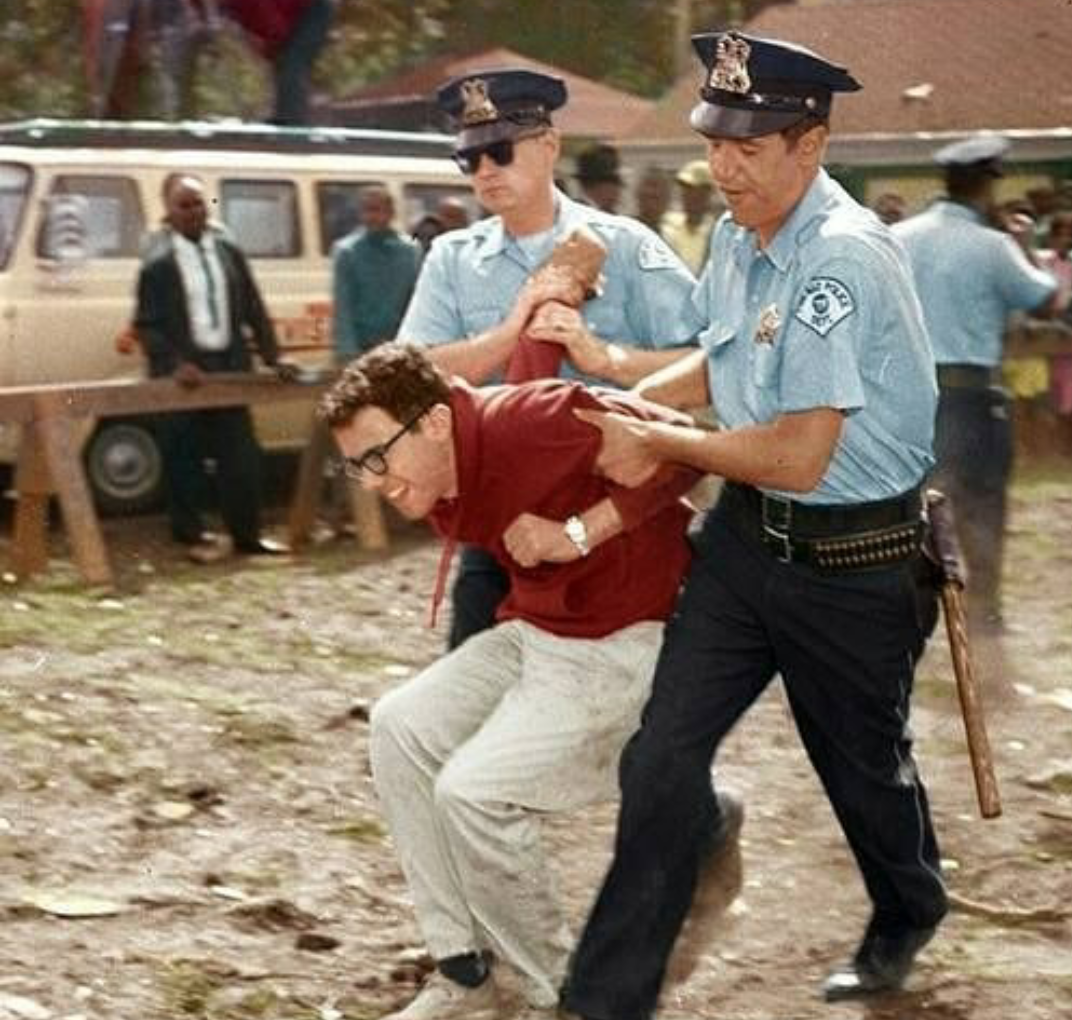

Sanders who claims to be a champion of fighting income and wealth inequality since before some of his Democratic rivals were born, and regularly brags about being jailed while attending a King rally during the civil rights era, exhibits the thought patterns of what the late Dr. Martin Luther King described as a ‘white moderate.’

Dr. King wrote the following about 'white moderates' in his 1963 letters from a

Birmingham Jail –

One occupation that black men in this land have consistently

worked in since before the founding of America is construction. As black chattel

slaves, not service workers like those in Bernie’s Vermont, black men & women worked as unpaid

free labor, under torturous conditions, and practically built the cornerstones

of the American infrastructure we enjoy today.

Historically, after the abolishment of chattel slavery in America, white American workers quickly organized labor unions, and sieged on the opportunity to corner the labor market for industrialist, by consolidating the work force under their unilateral control for the betterment of the ‘white working man.’

Sanders, a good ole boy representing Vermont, who plays

possum of the subject of reparations, and the ill effect of America’s blood

stained past of chattel slavery, is unequivocally a big time labor union

supporter, and is very imaginative when it comes to ways he can directly help promote

their interest.

For example, Bernie proposes “card check,” the process by

which unions can easily organize a worksite and also supports bailing out

underfunded union pension plans by raising taxes on wealthy Americans.

Sanders proposed ‘Keep Our Pension Promises Act’ which targets

so-called multi-employer pension plans, typically run by construction unions.

Nearly a third of these construction union pension plans are seriously

underfunded and heading toward insolvency, for reasons such as failure of their

unions trustees to invest wisely.

Yet while Bernie expresses his attentiveness and concern for majority white construction labor unions, and as employment in the construction labor market is expected to grow much faster than all other areas of occupation over the next decade, many black workers, particularly the sons of those that built the nation, black male descendants of chattel slavery, are all but denied traditional access to high paying construction union trades.

In exchange for careers as skilled tradesmen, the majority of black men entering the construction trade unions are herded into what Calvin Clinton, the President of the African American Workers Union (AAWU) describes as the ‘Jim Crow Construction Scheme,’ comprised of ‘pre-apprenticeships’ and ‘Title 3’ work force initiatives that far too often leads black workers back to unemployment lines.

The practice of immediately firing or laying off black construction workers once local hiring requirements have been satisfied, or the project has ended, which ever comes first, is commonly referred to in the industry as the 'One & Done' policy. The 'One & Done' policy is responsible for deterring thousand of black construction workers from become professional tradespeople.

VIDEO: Calvin K. Clinton, President of AAWU explains the 'Jim Crow Construction Scheme'

Senator Sanders who has been very imaginative when creating

solutions for his state, labor unions, and immigrant workers, has not yet written nor sponsored any

legislation that would drastically help struggling black descendants of American

slavery, being victimized by the discriminatory practices of the construction

unions he wants to bolster.

Today, if you take a look at just the mid-western United States, you will see in states all across that region that the black male unemployment rate is at alarming numbers, with Illinois being the worst of the bunch. All across American in other states such as New York, Texas, and California the black male unemployment rate is averaging emergency levels. Even after the stimulus packages of Bush, the quantitative easing of

Obama, and the dramatic posturing of Trump, the overall unemployment number for

black workers as a whole is still double that of white workers in America.

The historic fact that black unemployment has always been

double, or even more than double that of white workers, finds its roots in

government sponsored chattel slavery.

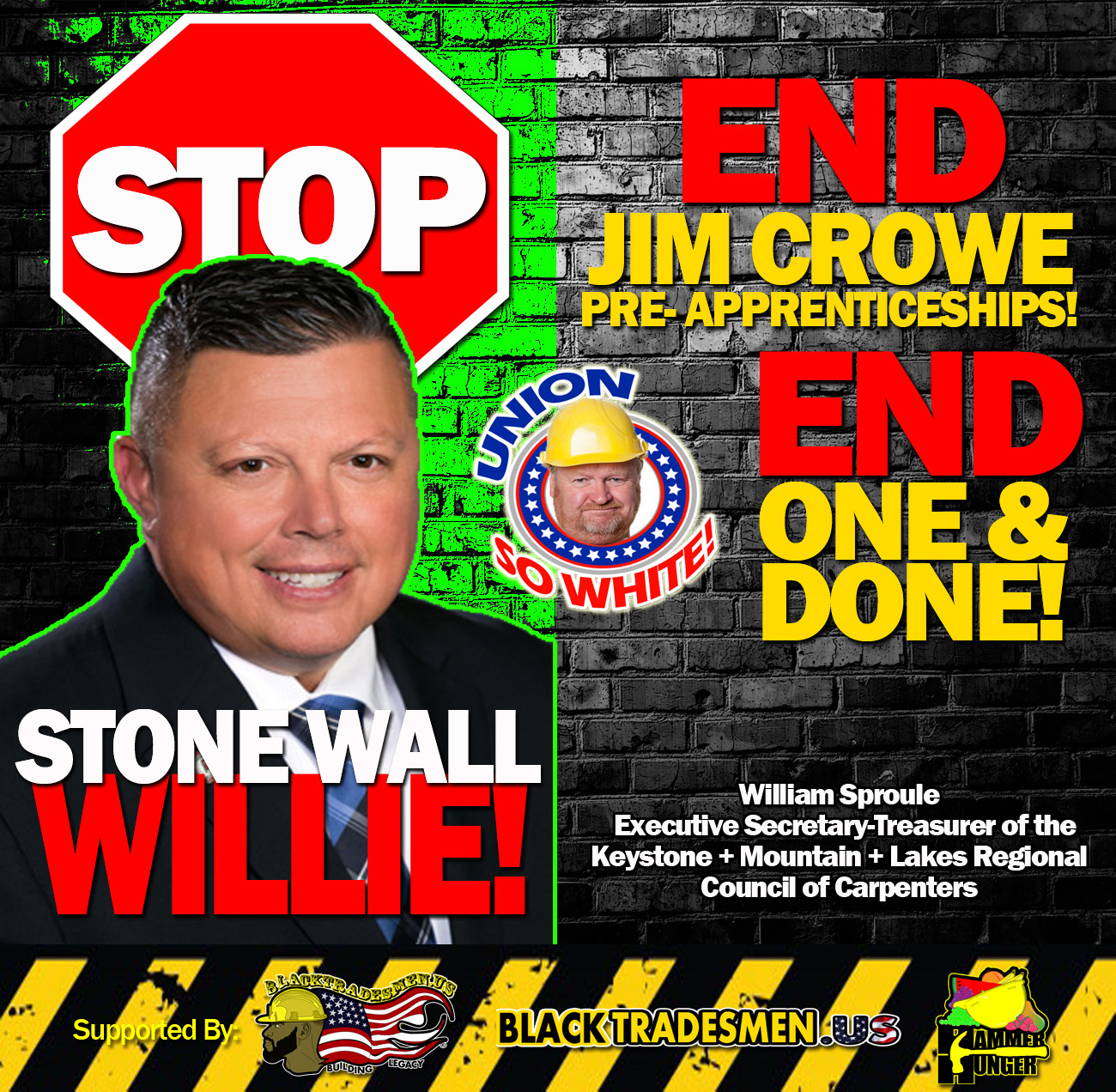

The Carpenters union in Philadelphia is attempting to

distance itself from an official with one of its local chapters who wore

blackface in this year’s Mummers Parade.

Mike Tomaszewski, one of the Froggy Carr Wench Brigade

members who painted their faces black during a Gritty-theme performance, is an

elected delegate for the 4,000-member Local 158, which represents carpenters

who live in the city of Philadelphia. Asked on New Year’s Day why he wore

blackface, Tomaszewski said: “'Cause I like it. Yeah, why not? I know it’s a

shame to be white in Philly right now."

William C. Sproule, executive secretary-treasurer of the

Eastern Atlantic States Regional Council of Carpenters, said in a statement

that the union was “disheartened” to learn Tomaszewski was involved in the

blackface incident.

“Racism is something our union denounces," Sproule

said. "Actions like this counter our union’s mission to be a diverse and

inclusive union that provides opportunity for all workers looking for a career

in construction. While we cannot control the personal views of a member, we do

work to continue to create a culture at all levels that is welcoming to all. We

are looking into this matter further.“

Asked if the union was considering taking action against

Tomaszewski, Sproule added: “The council is reviewing the conduct and the

applicable case law in respect to said conduct.”

Multiple attempts to reach Tomaszewski were unsuccessful.

Even as a majority of Philadelphians identify with racial

minority groups, the building trades unions are overwhelmingly white and have

long dealt with accusations of racial discrimination. It’s a politically

sensitive issue because of the influence wielded by the deep-pocketed trades

unions’ in city elections.

“The fact that he’s in a union — and Philadelphia is a city which has a legacy of racism in its unions — is not shocking,” said Tufuku Zuberi, a University of Pennsylvania sociologist who studies race relations. “This union, which is harboring such behavior, needs to be called in question.”

Building trades union leaders have disavowed the overt

racism of the past and promised to diversify their workforce. Critics say the

progress has been too slow.

The trades unions do not regularly disclose demographic information about their members. A study produced in the Nutter administration found that in 2007, 74% of the trades union workers were white, and 70% lived outside Philadelphia. In 2012, another study found that 76% were white and 67% were suburbanites.

The issue resurfaced recently as City Council members pushed for stronger diversity goals for construction workers who get jobs through the Rebuild program, which uses revenue from Mayor Jim Kenney’s sweetened beverage tax to improve city libraries, parks, and recreation centers.

“I’m not surprised,” Rodney Muhammad, president of the

Philadelphia chapter of the NAACP, said when told Tomaszewski was a Carpenters

official. “I don’t know if his sentiment comes from being a carpenter. It’s

just unfortunate that the trades have had a practice that has been criticized

publicly for decades now in the city of Philadelphia.”

Muhammad said he has been working with leaders of the trades on diversity efforts and is hopeful recent initiatives, such as a Carpenters program to consider formerly incarcerated people for apprenticeships, will produce results.

The history of racial exclusion in the trades unions is

deeply entwined with the era of minstrelsy, the racist 19th century American

form of entertainment that introduced blackface into Philadelphia’s iteration

of the medieval European tradition of mummery.

“In effect, the unions became the gateway for ordinary white

workers to gain access to a fairly good living in the American society,"

said Molefi Kete Asante, chairman of Temple University’s Department of

Africology and African American Studies. "But at the same time, for most

of the history of the unions, it was not the gateway but a closed door to

African American workers.”

Walter Licht, a labor historian at the University of

Pennsylvania, said he was not surprised to learn one of the Mummers who wore

blackface was a union carpenter.

“It doesn’t surprise me, because those legacies have been

there, and they have been, in a place like Philadelphia, hard to break. It’s a

solidarity, and within those solidarities there’s an ethnic component,” he

said. “They’re protective of their union and their community because it’s an

incredible ticket.”

CREDITS - This article is was originally posted at The Inquirer by Sean Collins Walsh, Updated 1/10/2020

ADDITIONAL NOTES>>>

William Sproule is the Executive Secretary in charge of the

Keystone + Mountain + Lakes Regional Council of Carpenters (KMLRCC). Willie

earns $250,000 a year. Willie & the KMLRCC represents more than 40,000

Carpenters in Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, New Jersey,

Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia and 10 North Carolina counties. Over 75%

of his Carpenters are white.

Willie helps create and supports Jim Crowe era

'Pre-Apprenticeship Programs' throughout his regions black communities. These

'Pre-Apprenticeship Programs' are designed to block black workers seeking to

enter the Carpenters Union by forcing them to complete unnecessary training's

and so-called 'Construction Boot Camps' before gaining entry to the same

traditional state sponsored Apprenticeship programs as other workers.

Carpenters Union 'Pre-Apprenticeship Programs' effectively create a stone wall that blocks black workers from ever becoming fully vested union members. In Fact, 97% of ALL graduates from a construction 'Pre-Apprenticeship Program' never become Journeyman level tradesmen, and never earn top union pay, nor do they receive retirement benefits. In most cases, black 'Pre-Apprentice' are brokered out to contractors seeking to meet local labor hiring agreements (PLA), these black workers are then paid the lowest industry wages and fired immediately after the projects end - This is called the ONE & DONE Policy.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE - THEN

CALL WILLIAM SPROULE @ (412) 922-6200 TELL HIM TO STOP STONE WALLING BLACK

WORKERS IN DELAWARE, DC, MARYLAND, VIRGINIA, AND N.CAROLINA, END

PRE-APPRENTICESHIPS AND THE ONE & DONE POLICY NOW!!!

Today, operating mostly as an underground, yet still highly relevant and highly effective organization established to maintain white superiority, the 'Knights of the Ku Klux Klan’ (KKK), who were a spin off from the Freemasons after the American Civil is a terrorist group that still has its poisonous tentacles operating secretively in all areas of American government, law enforcement, education, media, and oh yeah, labor.

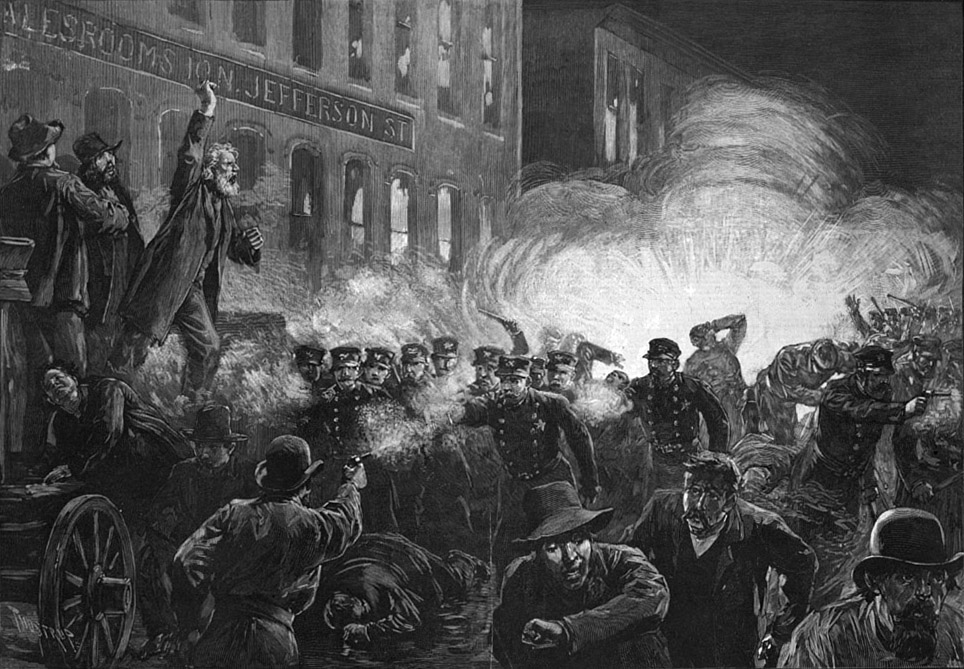

The most infamous of these unions was the ‘Noble and Holy

Order of the Knights of Labor’, later renamed ‘The Knights of Labor’ (KOL), which

was the first national industrial union in the United States. Founded in Philadelphia

in 1869 by Freemason Baptist Preacher Uriah Stephens, along with eight others,

‘The Knights of Labor’ was established as a platform on which to build white

working-class unity. While Freemasonry tended to attract members of the

economic elites, especially white merchants, retailers and investors, the

‘Knights of Labor’ membership encompassed all elements of the white working

class.

Founded four years after the creation of the ‘Knights of the

Ku Klux Klan’, Stephens also stressed the importance of solidarity within the

ranks of the ‘Knights of Labor’ in order to facilitate white superiority over

black American workers. He felt that the union should be a voluntary group of

white men working cooperatively and fraternally to safe guard white worker’s

interest.

This KOL method of accepting small amounts of black workers,

and separating black workers economically from other black workers performing

the same trades, has proved very fruitful for today’s American labor unions. By

harnessing some black worker support, the KOL was able to appear to the public

as a moderately progressive organization, while spearheading white male

dominance over the entire American workforce.

Black tradesmen that became members of the KOL were only

allowed to meet separately from white KOL members, in segregated union halls, with

white supervision, and had little if any vote on the organizations overall

policies.

Black only KOL union members were relegated to work only in

black communities, and amongst themselves. In fact, the modern construction

industry today in the U.S. finds its historic roots tied to this legacy of

castigating black tradesmen to the same effect when implementing so-called

‘Project Labor Agreements’ (PLA) and ‘Local Hire Programs’ primarily targeting

black workers. The modern PLA is a direct spin-off from the Knights of Labor

racist policies from over 100 year ago.

Racial divisions within the Knights of Labor were primarily

leveraged to prevent unity amongst black working class people and derail collective

bargaining efforts, which would have resulted in true economic gains for the

black working class.

It's been said that white supremacist always play both sides

of an argument in order to draw victory by any means possible for the white

race. While the KKK was the premier ultra-violent right-wing, the KOL was setup

to serve as the quintessential blue collar left-wing of the white supremacists

Masonic orders of Freemasonry. Both organizations used secret rituals borrowed

from Freemasonry when meeting in private.

Take for example the Thibodaux massacre of 1887 , which

killed more than 50 black members of the Knights of Labor, following a

three-week strike during the critical sugar harvest season by an estimated

10,000 workers, mostly black, against sugar cane plantations in Louisiana.

The strike was the first conducted by the Knights of Labor, who strongly

opposed strikes, due to their secret alliances with white elites.

The Opelousas Courier , a black owned newspaper described the scene:

'Six killed and five wounded' is what the daily papers here

say, but from an eye witness to the whole transaction we learn that no less

than thirty-five "...fully thirty negroes have sacrificed their lives in

the riot on Wednesday..." Negroes were killed outright. Lame men and blind

women shot; children and hoary-headed grandsires ruthlessly swept down! The

Negroes offered no resistance; they could not, as the killing was unexpected.

Those of them not killed took to the woods, a majority of them finding refuge

in this city.'

During and even after the Thibodaux massacre the Knights of Labor

did nothing to neither protect nor stop violence perpetuated by their democratic

Klan brothers against their black union members.

Albert Pike, who held the office of Chief Justice of the Ku Klux Klan while he was simultaneously Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite, Southern Jurisdiction expressed his concept of Masonic brotherhood’s such as the Knights of Labor allowing black members to join:

"I took my obligation to White men, not to Negroes. When I have to accept Negroes as brothers or leave Masonry, I shall leave it."

Historically, the KOL presented itself as an organization

committed to seeking major political reforms. Their leaders proposed reforms

such as the eight-hour day, the end of child labor, equal pay for equal work,

and a national income tax. But, KOL was completely ineffective at protecting or

even promoting any initiatives or reforms that would directly benefit American black

workers, who at the time were being lynched by the thousands. Black workers could

not vote, attend public schools, travel freely, or benefit from the fruits of

their labor in any meaningful way.

The Knights of Labor felt that they had been ordained by god, and that their effort to unite the white working class was a holy endeavor. Stephens expressed his conviction that the "Everlasting Truth sealed by the Grand Architect of the Universe" (God) is that "everything of value, or merit, is the result of creative Industry."

By promoting the KOL as a holy cause, the union was

successful at galvanizing white workers that feared they were losing power in

the workplace as black workers began to compete for the same jobs. White KOL

members were taught that they were the victims of ‘wage slavery’ and unfair

‘labor monopolies’ that consisted largely of black workers being manipulated by

white elites.

Similar to today’s skilled trade unions, the ‘Knights of Labor’ fraternal symbolism of white superiority was integrated into every activity of its members and provided them with common patterns of behavior, and a code of conduct. Borrowing from their freemasonry origins the KOL created emblems, and badges that evoked behavioral and psychological responses from its members who looked at themselves as militant protectors of the white working man, and related to one another in the same manner in which the symbols derived, as devout white supremacists.

In his doctoral dissertation, "Beyond the Veil: The Culture of the Knights of Labor"(UMass:1990) Robert Weir notes,

“By layering of symbol upon symbol, a psychic universe is created in which all parts relate to and define the whole.....Few fraternal orders created transcendental mental landscapes as well as the masons. This is precisely why the Knights of Labor drew so heavily upon Masonic ritual when articulating its own”.(pg. 18)

And, as the first local Master Workman, the first District Master Workman, and the first Grand Master Workman, the highest position in the organization, Stephen created the Knights of Labor’s emblem, an equilateral triangle within a circle, surrounded by a pentagon, and encompassed by an upside down five point star. Stephens embellished the emblem with symbols from the various white supremacists Freemason lodges to which he belonged.

The KOL felt that they had to have a public agenda and a

private agenda, they strongly opposed labor strikes and boycotts, and they felt it was

important to mask the fact that their unions leaders answered directly to the

same monopolistic elites they were purportedly fighting. By effectively using

symbolism, the KOL was able to rally its white racist base while also clamoring

for support from wealthy white masonic elites.

Although the Sugar Cane strikes of 1887 known as the Thibodaux Massacre, which

killed and wounded more than 300 black KOL members was the first strike the union

had conducted. In its early years, the Knights of Labor strictly opposed the

use of strikes and boycotts against industrialists.

The KOL white member base won important strikes to move the

needle for white workers , such as on the Union Pacific in 1884, and the Wabash

Railroad in 1885.

By the beginning of 1886, the Knights of Labor had over 1

million members across the United States, and Canada, and had chapters also in

Great Britain and Australia. Those successful

strikes during the mid-1880s led to the Knights of Labor's growth. As the

strikes proved successful, more workers flocked to the union movement.

But, due to the Knights of Labor's upper leaderships continued

opposition to strikes, and the leaders allegiance to wealthy masonic elites and

industrialist, the organization experienced declining membership by the late

1880s and the early 1900s.

And as lingering Klan sympathies among its union members became more prevalent, disgruntled KOL members began to establish and join other bigoted white supremacist labor unions, such as the United Brotherhood of Carpenters (UBC), established in 1881, the American Federation of Labor (AFL), established in 1886, the International brotherhood of Electrical workers, established in 1891, Laborers' International Union of North American (LIUNA), established in 1903, and International Brotherhood of Teamsters, also established in 1903, who refer to themselves as the ‘Knights of the Highway.’

As KOL members began migrating to newly founded labor unions

that they felt better served their interest, such as the AFL-CIO that used KKK

style violence, and intimidation against black workers, and as KOL union

membership began to dwindle on paper, the Knights of Labor’s leadership and

their Freemason puppet masters realized that it would be far more beneficial to

realign itself with Klan values as well, as it became a part of what the Klan describes

as the ‘invisible empire.’

Although the Knight of Labor was dissolved in 1949, we can still see the influence that secret societies like Freemasonry still have in today's labor union and labor movements. History tells us that as black workers we must stay alert to its secretive methods, and eliminate union leadership who promise much and deliver little.