HOW TRUMPS IRAP's WILL AFFECT BLACK APPRENTICES AND LABOR UNIONS

Apprenticeship programs can and should be a broadly

accessible path to high paying careers that pay a living wage. However,

currently, too many workers, particularly black/African American workers - face

difficulties accessing these programs, especially the programs that pay the

highest wages.

The U.S. system of registered apprenticeship has been responsible for putting more Americans into the middle class over the last 80 years, than any other form of education in the U.S.

Apprenticeship is, hands

down, the country’s most effective education and employment model, especially

for the construction industry. Imagine earning a quality education, graduating

with no debt, and transitioning directly into a career paying more than $60,000

a year, this is a reality for most apprentices in America.

But, in contrast to the German and Swiss apprenticeship

systems, where upwards of half of all young people, millions of them are

prepared for a range of careers through apprenticeship; whereas the American

system serves just over a half a million apprentices in any given year, and

prepares them primarily for careers in the skilled trades.

Aside from the traditional construction related apprenticeships, the Trump administration over

the past 2 and a half years has embarked on a mission of expanding

apprenticeship programs into new industries, such as health care and

information technology, with a goal of better connecting these apprentices to

higher education.

The Trump administration in fact, is building an entirely

new system of ‘industry-recognized apprenticeship programs,’ or IRAPs.

TRUMPS IRAP’s ARE

EXPECTED TO CHANGE THE GAME

IRAP was born out of President Donald Trump’s 2017 Executive

Order to Expand Apprenticeship in America.

In section 8 of the order, the Secretary is directed to establish a Task

Force on Apprenticeship, bringing together industry and workforce leaders to

consider how to promote apprenticeships especially in sectors where they are

insufficient.

The Presidents program is designed to expand apprenticeship

opportunities and give business more say in crafting training programs.

Although the construction industry is lacking trained, qualified skilled

workers at a record number, in its roll out, the administration will exclude

the construction industry from participating in the IRAP.

Effectively, privately ran IRAP’s will massively overhaul

apprenticeship regulations, and be governed by a distinct set of new

requirements, and quality-assurance processes that, the administration argues,

will make it easier for sectors like IT and health care to adopt apprenticeship

programs, and closely institute them under federal employment guidelines, such

as anti-discrimination policies which for years have been outright ignored by

some unions and privately recognized apprenticeship programs.

As the Trump administration continues to make investments

necessary to grow apprenticeship programs, their policies must center on

helping black workers, and other underrepresented groups to ensure equitable

access.

There is a lack of resources and social networks in the

black/African-American community to get into many high paying jobs, especially

those that lead to long-term careers like the one’s apprenticeships provide.

Apprenticeship programs offer one of the few career pathways

to people without college degrees, with few skills or with criminal records.

But entry into union ran apprenticeship programs are extremely competitive.

For the highest-earning apprenticeship programs, like electrical and sheet metal work, applicants must pass an entrance examination that tests math skills, among other abilities, and then interview for these positions under adverse scenarios, many times battling internal hiring practices such as nepotism.

This is why the Trump administration and the DOL

must include the construction industry into it’s IRAP initiative.

BLACK APPRENTICES FACE DISCRIMINATION

Although, Registered Apprenticeships are apprenticeship

programs that are registered with the DOL and are governed by regulations laid

out under the National Apprenticeship Act.5, and although these regulations lay

out labor standards for these programs and govern their Equal Employment

Opportunity (EEO) rules, many black/African American apprentice file

complaints, and lawsuits claiming damages due to massive amounts, and sometimes

organized acts of discrimination and exclusion from federally recognized

apprenticeships.

Currently, EEO rules prohibit apprenticeship sponsors - typically employers or unions—from engaging in discrimination, as well as require them to take affirmative steps to ensure EEO, including efforts to recruit from a broad pool of potential apprentices. Furthermore, programs with five or more apprentices are required to develop a written affirmative action plan and conduct an apprenticeship utilization analysis to ensure that they are drawing adequately from the local pool of available workers.

Yet in 2017, 63.4 percent of individuals who completed

Registered Apprenticeship programs were white, 10.7 percent were Black/African American, and 20.5 percent did not provide their race to their

Registered Apprenticeship sponsor at all.

According to many studies, one challenge in identifying

trends in apprenticeship participation by ethnicity and race is that the share

of those who do not provide their ethnicity or race. The lack of reporting has

increased significantly over time with Hispanics, with 29 percent of Hispanic

apprentices refusing to provide their Hispanic ethnicity in 2017—up from 3.3

percent in 2008.

Policymakers insist that this issue should be resolved immediately as more accurate data on the racial and ethnic composition of apprentices are necessary to conduct a fair equity analysis.

BLACK APPRENTICE FACE

UNFAIR COMPETITION

In many cases after completing stringent and intense union

ran apprenticeships, black/African-American apprentices find it difficult to

find work.

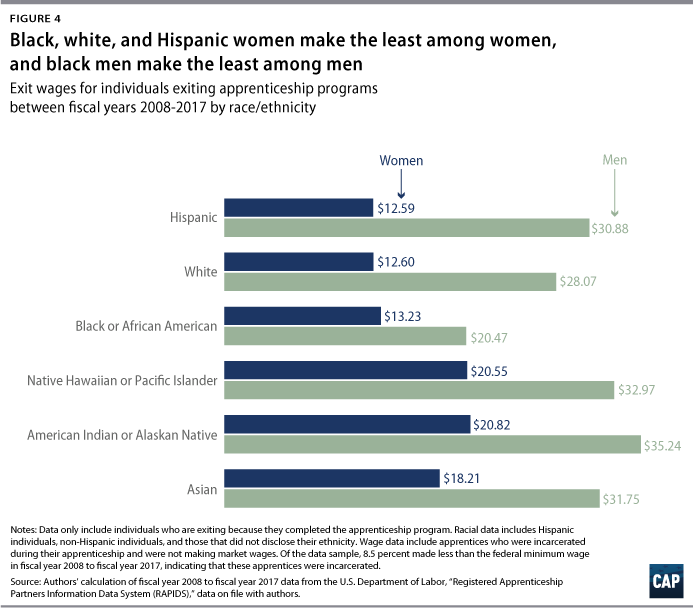

Black/African American apprentices had the lowest exit wages

of all racial and ethnic groups examined, at $14.35 per hour in fiscal year 2017.

White apprentices had the second-lowest earnings at $26.14; although white apprentices earned more than 50% more than Black/African American apprentices’ wages.

Median wages for Hispanics/Latinos completing apprentices

were the highest as they earned around $30 per hour.

One of the reasons that wages for Hispanics/Latinos apprentices are so much higher may be that they are more likely than black and white apprentices to complete their apprenticeship programs in Western states versus the south.

From fiscal year 2008 through fiscal year 2017, exit wages

for apprenticeship programs were highest in Western states at $32.50 and lowest

in the Southern states at only $20.80.

DACA

Another reason for the huge difference in wages amongst Black and Hispanic apprentices can also be attributed to large populations of 'non-citizen Hispanic' workers in Western states that are participating in the workforce,aat the union and non-level.

Many DACA recipients are also members of union ran apprenticeships, using employment

authorization cards (work permits), often issued through the Deferred Action

for Childhood Arrivals program known as DACA that President Barack Obama created

in 2012.

The DACA program, which was established without congressional approval, has protected 670,000 undocumented immigrants from deportation and enabled them to get work permits, and enter into apprenticeships, these people are commonly referred to as 'DACA recipients'. or'Dreamers.'

This work permit not only gives illegal alien workers the right to work in the U.S., it also creates unfair competition for native born, foundational black American apprentices seeking employment in the same trade fields.

The Trump administration and his justice department is preparing to end the DACA program altogether, which has prompted the Supreme Court to intervene, the court’s decision on rather its lawful for Trump to end the DACA program iexpected to be decided in the midst of the 2020 presidential election.

HOW WILL TRUMP

FIND FUNDING FOR IRAP’s?

“I don’t think

there’s going to be any takers because there’s no money,” a trade group

lobbyist told Bloomberg Law.

The Labor Department’s (DOL) announcement about the

implementation of this new nationwide apprenticeship program has some unions

and trade groups at arms with the department. Although the Trump administration

has not allocated any federal funding for these IRAP’s, that may be changing,

as it seems increasingly likely that the IRAP programs will become eligible for

federal funding.

According to Bloomberg Law, the Labor Department has a few

places where it can look for cash to fund IRAP grants if Congress decides not

to specifically appropriate money for the program.

That includes using funds allotted for the H-1B visa

program, which the DOL has wide latitude to spend as it sees fit. The H-1B visa

program offers temporary employment permits to foreign workers in the U.S. tech

jobs and other specialized occupations.

President Trump has mentioned his planned overhauls for the

H-1B program in the past, and has stated that he may reallocate funds from this

program to benefit American workers thru IRAP’s. In fact, late last summer, DOL

issued a funding opportunity announcement (FOA) outlining $150 million in grant

awards for apprenticeship programs, derived from fees paid by employers to

sponsor H-1B visas for workers coming from abroad.

Congress, both republicans and democrats, continue to demonstrate

their support for expanding apprenticeship programs. In 2016, DOL received $90

million in the first-ever congressional appropriation targeted specifically at

apprenticeship expansion. Since then, this amount has climbed steadily—$95

million in FY 2017, then $145 million in FY 2018, then $160 million in FY 2019.

And, although the Department of Labor has established that

IRAPs will not initially affect the construction industry or military apprenticeships,

many labor unions see IRAP’s as a future threat to their long established apprenticeship

programs.

UNIONS PREPARE FOR

WAR

Jim Reid, the apprenticeship director for the International

Association of Machinists, said the DOL’s efforts to fast-track the establishment

of IRAP’s has purposefully left out many union voices.

While many unions and trades groups are arguing that

privately ran IRAP’s pose a threat to their established apprenticeship programs, that have been historically white,

many others argue that IRAP’s will offer opportunities, and specialized training

to black workers that are employed more than 50% as non-union workers, and are

excluded from union ran apprenticeships at alarming numbers.

Worried that IRAP regulations and accrediting standards will

eventually crossover into the construction industry, many labor unions are

warning the Trump administration against such action. Union representatives are

warning Trump that if his administration winds up breaking from its commitments

to exclude construction in the proposed rule, the building trade unions are

prepared to abandon their support of Trump.

A brief look at many labor uniots twitter and Instagram pagess over the weekend show that union leadership is preparing to mount a public campaign attacking IRAP’s and the administration for what they feel will undermine union-protected wage and safety standards, a building union lobbyist told Bloomberg Law.

At the moment some White House officials have been advocating for construction industry inclusion, a reversal on what Trump initially proposed, analit is alienating the blue collar organized union labor groups that Trump has been, and will be counting on for support in his 2020 re-election bid.

In it’s current form, the national apprenticeship system

sponsors of programs - employers, unions, community colleges - have to register

with a state or federal apprenticeship agency that, in turn, determines whether

their programs meet a set of regulatory requirements on things like program

length, balance of on-the-job training versus classroom instruction, and the

apprentices’ wages and working conditions.

IRAP REGULATIONS & UNION APPRENTICESHIPS

Under the Trump administration’s proposal, programs could seek formal recognition from the Labor Department through a new system of “program accreditation.”

To accomplish this, the Labor Department is planning

to recognize more than 70 individual IRAP “accreditors” and grant them

authority to determine if a program meets a set of high-quality apprenticeship

standards that the department spelled out earlier this year.

NABTU, an umbrella group within the AFL-CIO that represents

15 individual building trade unions, has supported the Trump administration,

but that would all change if builders, mainly non-union builders are allowed to

take part in IRAP, a building trade’s official said. At that point, the trade

unions would organize members to accuse the administration of betraying

commitments to blue collar workers, the official said, speaking with Bloomberg

Law on condition of anonymity.

Yet, the administration contends that The National Apprenticeship Act (NAA), 29 U.S.C. 50, authorizes the Secretary of Labor “to bring together employers and labor for the formulation of programs of apprenticeship. The U.S. Department of Labor (the Department or DOL) proposes doing so through a new program recognizing Standards Recognition Entities (SREs) of Industry-Recognized Apprenticeship Programs (Industry Programs).

This

new program is intended to harness industry expertise and leadership to meet

the United States’ skills needs in the twenty-first century.

Opponents of IRAP’s also argue that the proposed quality-assurance process for IRAPs closely resembles the national accreditation system of for-profit career colleges and trade schools.

Unions and other opponents of IRAP's say that IRAP’s will not be properly regulated for quality-assurance by the government, and will enable the rise of multiple accreditors with overlapping jurisdictions and competing standards, and will not provide clear mechanism for holding accreditors or programs accountable for poor outcomes.

In response the DOL proposes that the new IRAP Standard

Recognition Entities (SREs) will be recognized for 5 years. The SRE must

reapply if it seeks continued recognition after that time, using the same

application form it submitted initially. The Department proposes a 5-year time

period to be consistent with best practices in the credentialing industry.

IN CONCLUSION

The President and policymakers working to expand apprenticeships

should also work to eliminate occupational segregation in apprenticeship

programs to ensure that black/African-Americans have access to apprenticeship

programs in the highest-paying occupations.

Policymakers should also ensure that new IRAP regulations include the construction industry, while also ensuring apprenticeship programs

are required to comply and support wage progression policies that help ensure

that the highest-wage programs remain well-paying.

Furthermore, policymakers should seek to expand

apprenticeships into new industries, such as IT, healthcare, and childcare,

while increasing wages across the board.