Ray's article

ATLANTA STRIKE OF 1977

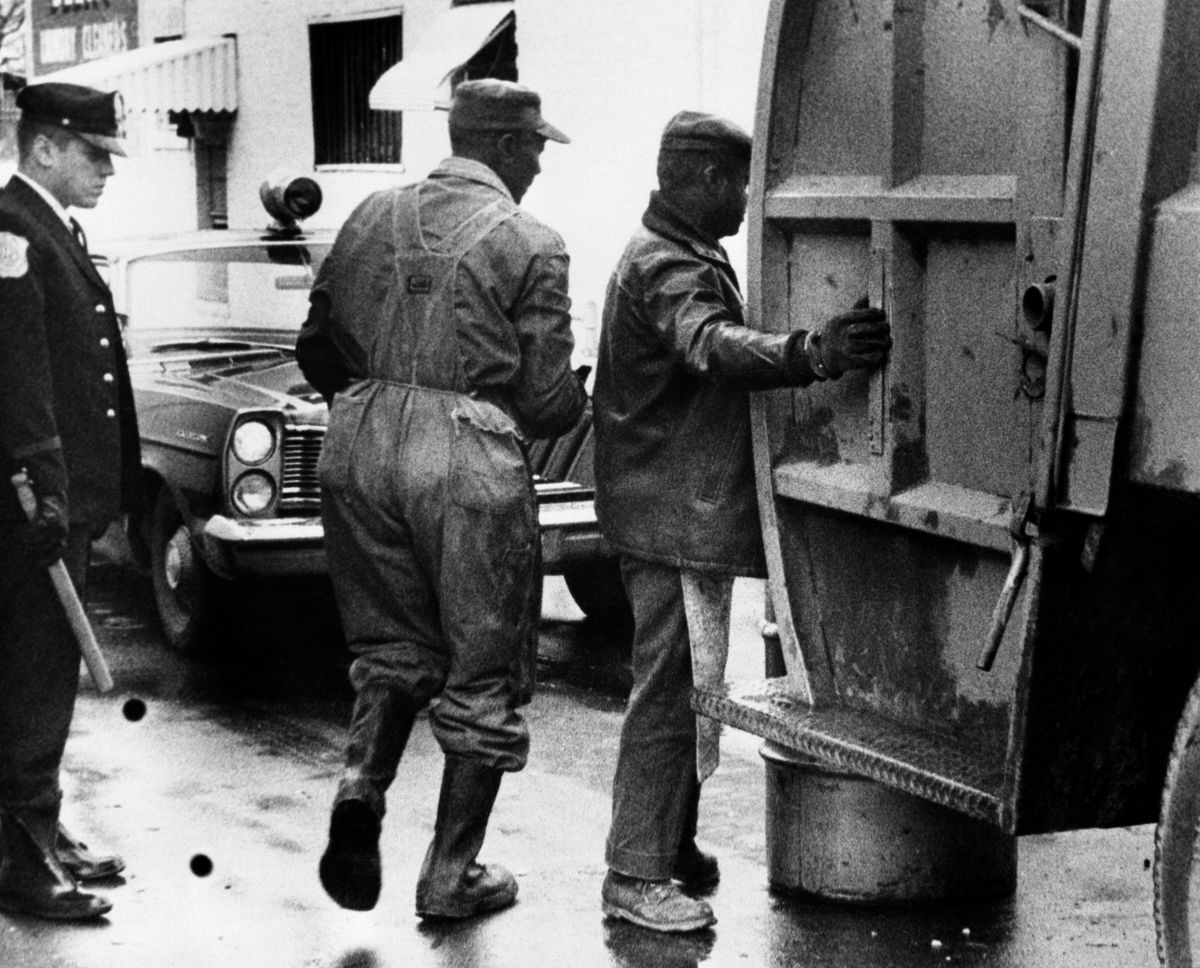

The sanitation workers strike of 1977 was a culmination of frustrating and contradictory relations with a new generation of ruling elites. Pivotal was the relationship between city workers, represented by AFSCME Local 1644, and Mayor Maynard Jackson. This relationship began in 1970 when sanitation workers struck for union recognition, higher wages, and change in the unequal social relations between city management and rank-and-file employees. Their demands mirrored those of striking sanitation workers in Memphis just two years earlier. Atlanta’s white mayor, Sam Massell, battled back by firing workers and using prisoners from city jails for garbage removal.[5]

Jackson, then vice-mayor and a former lawyer with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), publicly chastised Massell’s hard line tactics, supporting those on strike and calling their wages “a disgrace before God.”[6] This endeared Jackson to city workers, progressive whites, and many folks in the black community who helped elect him mayor in 1973. However it was Jackson who, by March 1977, became a “disgrace before God” in the eyes of those same city sanitation workers he supported in 1970, and who got out the vote for him two years later.

This contradiction showed Jackson’s success in preempting popular black support for the 1977 strike by municipal sanitation workers, nearly all of whom were black and who were easily the lowest-paid workers on the city government’s payroll. Jackson short-circuited union and worker attempts to build community support for the strike by portraying it as a racial attack by a white-led AFSCME on his administration. This, even though most of its local union leaders were black and had struck against the initial wishes of many whites in the union’s national leadership.[7]

This relationship helped form the foundations of social relations between largely black-run city government and everyday black folks they governed. This was the logical outcome of civil rights and Black Power struggles for self-government, for these movements at their philosophical core sought a seat at the table of representative democracy, rather than turning that table over in favor of a democracy from below. For many everyday black folks Maynard Jackson represented Black Power, and they believed his rise to power meant the city’s social and economic patronage circles would trickle down to them.

In the minds of the new black officials and perhaps the majority of working folks in the black community, the actions of striking sanitation workers threatened what they believed was Black Power finally achieved. The perceived gains for the black community would not be uprooted by class struggle under the watch of black officials and their supporters. This relationship continues today in Atlanta, where black officials receive wide support among folks of various class and ethnic backgrounds throughout the city.

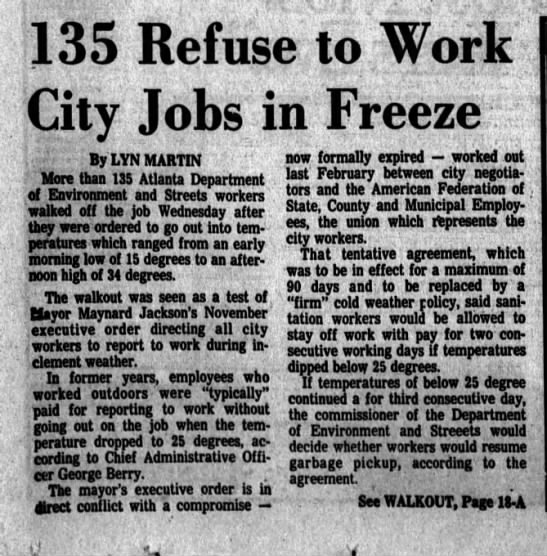

The 1977 strike occurred in two separate waves. The first played out during four weeks in January and February. It began with sanitation men wildcatting when they were told to report to work in cold weather conditions. The city and union had agreed employees did not have to work if the temperature was below 25 degrees, which it was on the 18th and 19th of January. City bosses ignored this agreement and docked employee pay.

Already upset their demands for higher wages were falling on deaf ears, many sanitation workers walked off the job for a week in February when city officials refused to reinstate pay.[8] Jackson and city officials refused to give in, demanding employees return to work or face termination. The move caused the ranks to waiver, with the majority of AFSCME Local 1644 staying on the job. A solidarity strike among waterworks employees also failed to materialize.

The city agreed to pay only half the wages docked. AFSCME local organizer Leamon Hood said the strike was not so much about the pay as “the principle of someone sitting in a warm office and telling you to go out in cold weather when you couldn’t even get the ice off the cans.”[9] It was the idea that sanitation workers should manage their workplace of their own accord, free of bosses sitting in the warm offices of city hall.

Another theme evident was that bosses failed to follow agreed upon work stipulations, and held it against workers when they dare follow the rules. This demonstrated the contempt city bosses had towards any terms of the contract or any other agreements favorable to working folks, showing how tenuous labor-management contracts really are. Won through the struggle and self-activity of workers, not dreamt from the minds of labor bureaucrats, contracts that supposedly govern workplace social conditions are never set in stone. Their gains must constantly be guarded by working folks against bosses who would assume they never existed in the first place. The strikes of January and February would serve as a prelude to events occurring some weeks later.

Bitter and emboldened by their experience in January and February, sanitation workers and AFSCME Local 1644 continued pressing the Jackson administration for fifty-cent-per-hour wage increases to a salary averaging $7,000 annually. This amount was below the national poverty line. Jackson refused, claiming raises would put the city budget into deficit. With Jackson up for reelection and seeking to shore up support among white business elites and middle classes, he did not want to be the first mayor since 1937 to take the city to the bank.[10]

Jackson claimed he felt sanitation workers deserved wage increases, but the city’s economic bottom line was obviously more important. AFSCME countered with full-page ads in the New York Times and Atlanta Constitution lambasting Jackson, claiming city budgets showed multi-million dollar surpluses that easily could cover wage increases for sanitation workers.[11] The line in the sand was clearly drawn, as it was clear Jackson, though claiming he “felt their pain,” would not acquiesce to sanitation worker demands.

The second strike began on March 28 and was fully supported by the over 1,300 rank-and-file workers of Local 1644. The strike was organized by local union figures like Leamon Hood, with support from national AFSCME offices through its president Jerry Wurf. A national ad campaign against Jackson and the city’s policies began with the union calling out his administration on cronyism. Locally, strikers staged pickets and direct actions, unfurling a banner during a nationally televised Atlanta Braves baseball game that read “Maynard’s Word is Garbage.”

Later, some strikers dumped trash on the steps of city hall against Jackson’s strike-busting tactics.[12] The rank-and-file appeared united, in it for the long haul, and ready for whatever city bosses could dish out. Jackson served striking workers pink slips, giving until April 1st for employees to return to work. Those individuals who stayed out after that date were fired.

Sanitation workers were shocked that a man, who in 1970 supported them against scabbing tactics by then mayor Sam Massell, resorted to and carried out mass firings. They could understand Henry Loeb and Sam Massell doing that to black workers, but not Jackson, seen as one of their own. The difference was in 1977 Jackson, unlike Loeb and Massell, had broad community support. He built a coalition between the old white business and civic elite and the black ruling elite forged from the civil rights establishment (also known as the “Black Boule”).

The new coalition proved very powerful in marshalling all of Atlanta official society and its supporters, among everyday working folks, against the strike effort.

The conditions that made this new coalition of elites possible have their roots in the Civil Rights and Black Power struggles. These movements for black liberation had many figures and tendencies advocating for reformist strategies, hoping to secure relative freedoms from a benevolent state and a seat at its table while suppressing movements edging towards self-government by black folks in communities and workplaces. The liberal civil rights agenda sought a more humane state and the election of leaders, black and white alike, who were not openly racist and could sympathize with the plight of working people.

Some aspiring political elites even came from humble backgrounds themselves, having personally felt the harsh realities of white supremacy in America. Figures and organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Urban League, Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and even among Black Power organizations like the Black Panther Party (BPP) and Congress of African Peoples (CAP) were instrumental in normalizing the participation of black folks in governance from the local to the national level.[13]

Though their struggles advanced liberation and self-governance for black folks (and all peoples for that matter) they ultimately ended in a reconstruction of liberal representative democracy. This new framework ultimately constituted, at its best, a progressive gloss over the state and institutions continuing to deny everyday folks governance of judicial, military, economic, and social affairs. This new progressive governance, including individuals from groups historically oppressed based on race, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation, today receives support, although at times unevenly and inconsistently, from both conservative and liberal groups and individuals in civic, political, and corporate realms.

This rainbow coalition of corporate managers and political ruling elites is now the normative mode of governance in an American society understood as multicultural. Only from this can one understand contemporary racist and imperialist policies against black people, at home and abroad, being legislated by “women of color” in government, or how corporations managed by individuals from historically oppressed groups can treat their employees, some who are from their same background, like dirt.

This explains how elites in business and government, no matter what their ethnic or racial background, gender or sexual orientation for that matter, have so much contempt for the working classes of their own background or identity. We also see this dynamic playing out between union bureaucrats and rank-and-file workers.

In America, this multiculturalism is subordinate to the legacy of white supremacy, not because White men put guns to the heads of black aspiring elites, rather because the latter freely accept their new power knowing it rests fundamentally upon social inequalities. White supremacy in the United States today depends on representatives from historically oppressed groups to assistant in its orchestration of social, economic, political, judicial, and military affairs. Atlanta politics and society in 1977 clearly shows these ideas and systems taking shape.

The actions of Maynard Jackson and black official society against mostly black sanitation workers makes sense when one views multiculturalism as such a veneer, covering fundamental social, political, and economic inequalities. Many Atlantans (black, white, conservative, progressive, male, female) accepted Jackson and other new black officials with little debate. This is also true among “radical” community activists, for the new black official politics were judged on criteria apparently inconsistent with the principled political ideas they normally defended.

This translated, for some, to new simplified standards qualifying black officials and aspirants to such status as racially authentic, anti-racist or progressive. In turn the new class of black officials made gestures toward community “radicals” and their immediate, non-threatening initiatives (for example, adopting an honorific street name or issuing a proclamation to acknowledge African Liberation Day, or appointing an activist to a commission or a job).

This was an unacknowledged concession to the ascendancy of the new black political elite, amounting to a de facto agreement. They would not challenge the new elite’s power in exchange for occasional symbolic nods of recognition in a perverse pageantry of legitimization through dependence. This orientation both reflected and reinforced radical forces’ increasing marginalization in the black community.[14] This made it easy for officials like Jackson to proclaim that their election to office signaled the final victory for Black Power, while conflating power now wielded by black political elites as the achievement of self-government for all in the black community.

The litmus test of anti-racism and authenticity remains shallow for black officials because their racial and ethnic backgrounds, in the opinions of many, automatically give them passing marks. The fact that black officials even exist, especially back in 1977, remains a source of pride and celebration among everyday folks, even if they disagree with many policies these officials pursue. This was understandable for a time, since black people had been denied power on any level for so long.

In Jackson’s case, he was widely celebrated in the black community as fighting for more contracts and jobs for blacks in the construction of Atlanta’s airport, renamed Hartsfield-Jackson airport shortly after his death in 2003. So when black sanitation workers challenged Jackson for better wages and workplace conditions, attempting to change unequal economic social relations in the city, it constituted a real threat to his power. In turn, ordinary folks also saw it as an attack on the black community at-large. This was not merely a struggle to rename a park or street after a heroic radical labor or black liberation figure, of which Atlanta is famous for doing. Rather it was a fundamental challenge to the power that black officials wielded against ordinary people in their workplaces and communities. This challenge was met with swift reprisal.

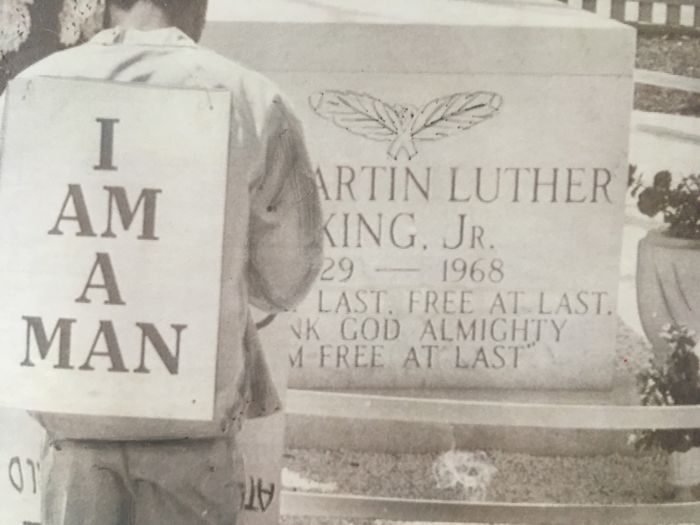

The events of April 4, 1977 are telling in the struggle between working folks and those who saw them as unruly individuals to be managed from above. On the ninth anniversary of the death of Martin Luther King Jr., both striking workers and city officials used his memory to justify their actions. In a rally for strikers, Rev. John Bell invoked King’s memory and assassination nine years to the day in Memphis. They reminded folks that he came to the aid of striking sanitation workers. Bell believed King’s spirit would lead the striking garbagemen to victory.The crowd cheered, though with trepidation as they knew hundreds of men were lining up for their jobs at that very moment as Jackson had fired them just three days earlier.[15]

At city hall there was a very different scene. Jackson called a press conference announcing that strikers would permanently be replaced with new hires beginning that very day. Jackson told the press his decision to fire striking workers was one of the most difficult decisions he had ever made. That comment proved quite empty, for he then reminded the press his actions enjoyed broad city support, from groups such as the Atlanta Business League, Chamber of Commerce, as well as from the Urban League, SCLC, the Atlanta Baptist Ministers Union, and the Citywide League of Neighborhoods among others.

This show of unity among the“good ole boys” of the white business and civic community with new

black officials and longtime civil rights establishment groups was really a

first for Atlanta, showing a maturation of a new political and economic ruling

elite.

The city’s major newspapers the Atlanta Constitution and the

black-owned Atlanta Daily World both publicly supported Jackson’s firing of

workers. It seemed all of Atlanta, black and white alike, were against the

strike.[16] But the real kick to the

stomach of the workers came later in the press conference when Martin Luther

King, Sr. spoke. He strongly supported the firings saying,“If

you do everything you can [for the union] and don’t get satisfaction…then fire

the hell out of them.”

When asked if his support of Jackson’s tactics meant he

endorsed strikebreaking, King responded, “We don’t like the word ‘break’ the

strike.”[17] But that indeed was

going on just as “Daddy King” spoke. Strikers

did not take the strike busting tactics lightly, and fought with scabs at

numerous hiring locations in the city.

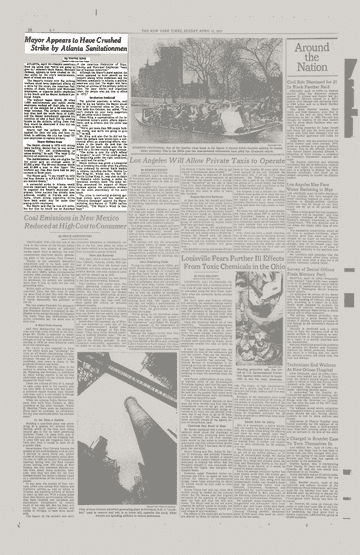

NEW YORK TIMES 1977 - Mayor Appears to Have Crushed Strike by Atlanta Sanitationmen

NEW YORK TIMES 1977 - Mayor Appears to Have Crushed Strike by Atlanta Sanitationmen

By mid-April, morale among strikers was faltering. Many

reapplied for their old jobs, forced into the humiliating position of standing

in line with scabs. A few rallies were still held, with one on April 12th

seeing garbage dumped on the steps of city hall, resulting in the arrests of a

number of protesters. Picket lines continued to thin out that week, to the

point where only 300 of the original thousand-plus workers stayed out. Though small in numbers, they continued

to rally.

Community support did exist in tiny numbers, even including

a few prominent figures from the civil rights era. One was CORE co-founder

James Farmer who served as director of the Coalition of American Public

Employees at the time. Farmer had supported Jackson, but was perplexed by his

tactics.[18] Another was Rev. James Lawson, a community leader in the 1968

Memphis strike. He compared Jackson to Henry Loeb. The Coalition of Black Trade

Unionist (CBTU) also supported the sanitation workers, chastising Jackson for using “Black workers as political pawns in his efforts to please a middle

class black political constituency and satisfy the black establishment.”[19]

Conclusion

Atlanta and other major U.S. cities like Detroit and

Washington D.C., where black officials are in the majority, have entrenched a system of ethnic patronage that is

fundamentally wrought under the weight of white supremacy. This system

rewards elites of all ethnic backgrounds who preside over city councils,

chambers of commerce, civic organizations, and union bureaucracies at the

expense of everyday working folks. In majority black cities like Atlanta, it is

black officials, in concert with the network of white business and civic

elites, who see to it their social and economic plans for the city go forward

with little or no challenge.

When individuals

or groups, like city sanitation workers did in 1977 Atlanta, struggle against

those who would see them as little more than spoiled, misbehaving children

asking for more than what little the bosses think they are worth, then all of

official society works to shut them down.

In Memphis, sanitation workers were able to flip the table

over on white supremacist social relations at work and in the community for a

time. This was not the case in Atlanta, where just seven years earlier

sanitation workers were supported by black civil rights establishment figures

as upholding the legacy of Memphis sanitation workers in their workplace and

community struggle against white supremacy. And yet those same establishment figures, now hailed as mayors,

councilpersons, civic and union leaders, portrayed the self-activity of these

Atlanta sanitation workers as a threat to the fabric of the community,

endangering the gains of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements that made

black officialdom a reality in the heart of Jim Crow.

The 1977 strike demonstrates that, no matter the background

of city bosses, working folks take a back seat to the social and economic

interests of ruling and aspiring progressive elites. With few people and groups

willing to challenge the power of today’s supposedly progressive overseers, the proud tradition of battle against white

supremacy and workers self-management in places like Memphis, Atlanta, and

throughout America during the Civil Rights and Black Power era seems like a

fleeting memory.

This scenario continues to this day in Atlanta, where labour

struggles by unionized and non-unionized workers in majority black workplaces

must battle black corporate and government bosses. A good example is the organizing by rail and bus operators for

Atlanta’s public transit system (MARTA) in 2005. They sought better pay and

benefits, and more control of workplace conditions. Their demands were blocked

at every turn by MARTA’s board,

consisting predominantly of black corporate and civic figures, even some

with ties to the old civil rights establishment that played a hand in crushing

the 1977 strike. MARTA workers were eventually forced to accept a largely

unfavorable contract, handed down by a judge, which saw many health benefits

and workplace control sacrificed for a very modest raise.

Time will tell when

everyday folks will finally be able to completely break through, tearing off

the progressive veneer used by today’s coalitions of ruling elites to cover

over the fundamental social, racial, and economy inequalities they carry on.

Originally published in New Beginnings, A Journal of Independent Labor

Notes

[1]See Godshalk, David

Fort. Veiled Visions: The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot and the Reshaping of American

Race Relations. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina

Press, 2005; Burns, Rebecca. Rage in the Gate City: The Story of the Atlanta 1906

Race Riot. Cincinnati: Emmis Books, 2006; and Bauerlein, Mark. Negrophobia: A

Race Riot in Atlanta, 1906. San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2001.

[2]At the River I

Stand. Dir. David Appleby. DVD. 1993. San Francisco: California Newsreel, 2004.

56min.; Beifuss, Joan Turner. At the River I Stand. Memphis: St. Luke’s Press,

1990; Green, Laurie B. “Battling the Plantation Mentality: From the Civil

Rights Act to the Sanitation Strike.” In Battling the Plantation Mentality:

Memphis and the Black Freedom Struggle. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University

of North Carolina Press, 2007, 251-287; Honey, Michael K. Going Down Jericho

Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign. New York: W.W.

Norton, 2007.

[3]Beifuss, Joan

Turner. At the River I Stand. 40.

[4]Ibid, 25.

[5]“City Employees in

Atlanta Vow to Escalate Strike.” New York Times (22 March 1970): 29.

[6]“1,400 Striking

City Employees In Atlanta Discharged by Mayor” New York Times (21 March 1970):

20, and McCartin, Joseph A. “‘Fire the Hell Out of Them”: Sanitation Workers’

Struggles and the Normalization of the Striker Replacement Strategy in the

1970s.” Labour: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 2.3 (2005):

70.

[7]Reed, Jr., Adolph.

“The Jug and Its Contents.” In Stirrings in the Jug: Black Politics in the

Post-Segregation Era. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999. 5. See

also Reed’s “Why Is There No Black Political Movement?” In Class Notes. New York:

The New Press, 2000. 3-9.

[8]Bell, Chuck and Jay

Lawrence. “City Workers Take Day Off.” Atlanta Constitution (8 February 1977):

10-C, and Lawrence, Jay and Valerie Price. “Garbage Workers on Strike.” Atlanta

Constitution (9 February 1977): 1-A, 1-F.

[9]Lawrence, Jay.

“Garbage Workers Back; Question Is, Who Won What?” Atlanta Constitution (15

February 1977): 8-B.

[10]Matthews, Tom and

Vern E. Smith. “Atlanta: The Strikebreaker.” Newsweek (25 April 1977): 29.

[11]“The Mayor and the

$28 Million. A Mystery Story.” Atlanta Constitution (8 April 1977), and New

York Times (27 March 1977).

[12]McCartin, 85, and

Martin, Lyn. “Protestors Dump Trash At City Hall.” Atlanta Constitution (13

April 1977): 1-A, 10-A.

[13]Numerous books

document the history of radical community and national groups being normalized

into positions of governance. See Komozi Woodard’s A Nation Within a Nation:

Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics about CAP in Newark.

[14]Reed, Jr., Adolph.

“The Jug and Its Contents.” In Stirrings in the Jug: Black Politics in the

Post-Segregation Era. 8-9.

[15]McCartin, 67.

[16]“Fire the

Strikers.” Atlanta Constitution (30 March 1977): 4-A, and Atlanta Daily World

(4, 7 April 1977).

[17]Lawrence, Jay.

“City Strikers Clash With Job Applicants.” Atlanta Constitution (5 April 1977):

2-A, and “Strike is Criticized by Dr. King’s Father.” New York Times (5 April

1977): 5.

[18]Matthews, Tom and

Vern E. Smith, Newsweek (25 April 1977): 29.

[19]McCartin, 86.

This article is a

case study of the betrayal of the African American working class by the Black

political class elites brought to power by the Civil

Rights and Black Power movements of the 1960's.

"A disgrace

before God"

Labor struggle in

the American South has a long and proud tradition. From the historic

textile mill strikes of 1934, to streetcar workers in 1949 Atlanta, to

sanitation workers in Memphis and St. Petersburg, Florida in 1968, working

folks have organized to control social relations and conditions of labor in

their workplaces, and to regain a semblance of their own humanity in the face

of attacks from company bosses, police, and government officials. And this was

all initiated with little or no formal union infrastructure or support. Yet Southern labor history is portrayed as

backward or underdeveloped in relation to the North, with its long tradition of

unions in large industrial cities like New York, Detroit, and Chicago.

Instead we see that Southern folks, blacks and whites alike, have struggled for

years against bosses running company towns with an iron fist, against Jim Crow

segregation pervading workplaces, neighborhoods and cities, and against all

authoritarian forces viewing organized labor struggles as the coming terror.

Workplace organizing among sanitation workers, by 1977, had

a proud history. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, in places like New York City,

Cleveland, Atlanta, St. Petersburg, and most famously Memphis in 1968,

sanitation workers, as individuals and as organized groups, battled city bosses

against slave wages, unsafe working conditions, and for the right to form

unions and workplace associations on their own terms. These struggles went hand-in-hand with the black liberation movement,

for defeating white supremacy was a challenge met in neighborhoods and in

workplaces.

The city recognized the strikers’ call for union recognition, nationally backed by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) and conceded to demands for better pay and improved workplace conditions. This scene repeated itself in St. Petersburg and Cleveland later that year. This also occurred in Atlanta in 1970, where civil rights figures, some of whom were newly elected city officials, supported striking sanitation workers threatened with termination by Atlanta’s white mayor Sam Massell.

Fast-forward seven years to the Atlanta of 1977 and

something strange, one may think, happened. The script was flipped. The same

black officials who supported sanitation workers against firings by a white

mayor decided to replace striking city sanitation employees with scabs. This

occurred with the full support of many old guard civil rights leaders and

organizations, allied with business and civic groups associated with Atlanta’s

white power structure during Jim Crow segregation. What explains the apparent about-face by black officials?

The Atlanta strike of 1977 shows the coming of age of a

coalition of black and white city officials, along with civic and business

elites, under the leadership of the city’s first black mayor, Maynard Jackson.

Just seven years earlier Jackson publicly sided with sanitation workers against

a white mayor seeking to fire them. Jackson and some members of the civil

rights establishment, in positions of local government by the mid 1970s, did

not hesitate to marshal the forces of official society against the

self-activity of black workers. They

allied with white business and civic elites, the same people that just a few

years earlier openly supported white supremacist segregation, all in the name

of smashing the sanitation workers’ strike by any means necessary.

The coalition of black and white elites 71 years later

helped foment class antagonisms that ultimately bubbled to the surface. The

difference from 1906 was blacks had a seat at the table of Atlanta city

government. The demise of the 1977 sanitation strike appeared to be a blow to

the black liberation struggle of the 1960s and 1970s, showing that its mainly

reformist victories actually signaled a defeat of the broader movement towards

anti-racism and self-government. It signaled to working folks, black and white

alike, that the promised land Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of while addressing

sanitation workers in Memphis, just a day before he was assassinated, appeared

open only to business, political, and religious elites.

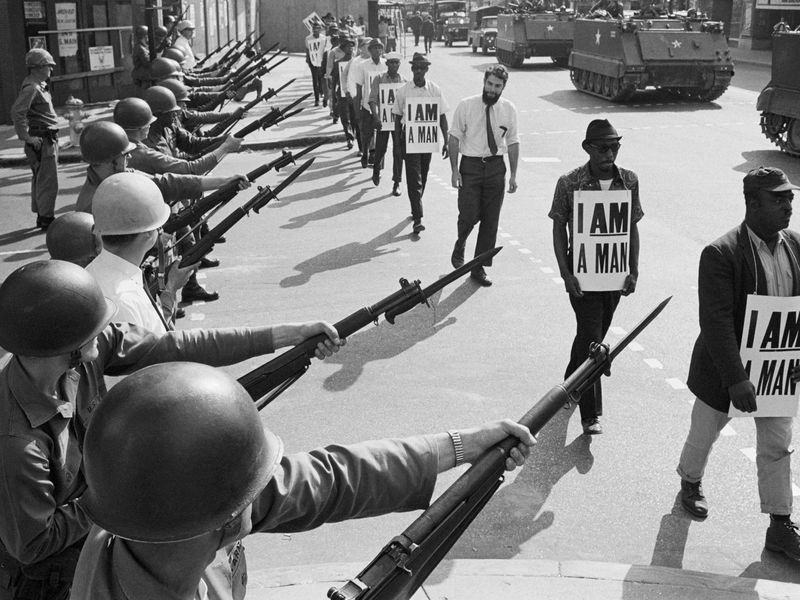

Memphis Sanitation

Workers Strike, 1968

This was evident in the treatment of city sanitation

workers. This job, socially open only to black men, paid such menial wages that

most workers lived below the poverty line. After numerous attempts to create a

union to counter the city bosses and improve social and material workplace

conditions, sanitation workers finally struck in February 1968. What ultimately sparked the strike was the

death of two men crushed by faulty garbage trucks. With no formal union support

through the national AFSCME leadership, who initially told folks to stay on the

job, men organized a complete work stoppage, asking for significant

improvements in pay, work conditions, and the right to unionize.[2]

Led by Mayor Henry Loeb, Memphis city government took a firm

line against these individuals that would dare challenge the social, economic,

and racial divisions prevailing in Memphis. But it would be white supremacists

like Loeb and his ilk who would be left rotting on the trash heap of history by

the strike’s end in April 1968.

Unionization efforts

began a few years earlier, led within the ranks by T.O. Jones. For his

efforts, Jones was fired, but he continued working towards unionization as an

organizer for AFSCME Local 1733. By the cold winter of 1968, sanitation workers

were tired of workplace conditions, faulty equipment, and pay ranging from $1.65

to $1.85 an hour for laborers and $2.10 for truck drivers.[3] The attitude of

city officials was demeaning, telling employees that going on strike was

unnecessary and illegal. Besides, sanitation workers were lectured, the

benevolent white city fathers took care of them anyway. However a critical mass of sanitation workers, with strong support from

the community, had become sick and tired of the city’s plantation mentality

that saw them as nothing more than misbehaving children.

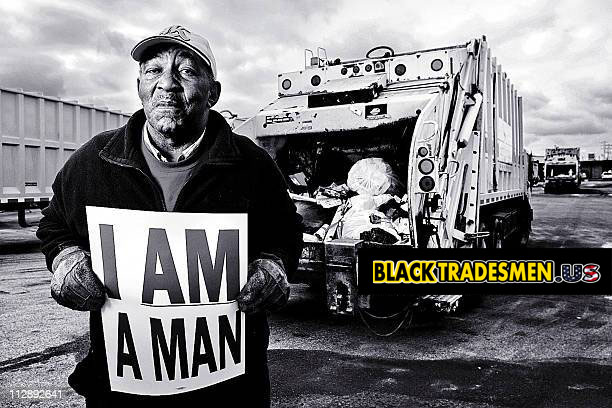

Striking workers countered by carrying signs proclaiming “I Am a Man.” It was not simply small

economic gains and improved workplace conditions motivating Memphis sanitation

men to organize collective labor action. Rather it was a call to change the

racist social and economic conditions black folks endured in Memphis. These

conditions had fundamentally not changed since the time of slavery. The new

society was breaking out of the old order where white supremacy had ruled

virtually unchecked.

At this historical moment of labor struggle by Memphis

sanitation workers, national leaders in AFSCME viewed their actions as

troublesome. When initially informed of

the walkout, AFSCME’s field service director P.J. Ciampa privately stated, “I need a strike in Memphis like I need a

hole in the head.” He also

chewed out T.O. Jones for helping start an illegal strike, though eventually

promised support from the national office.[4]

This was yet another

example in American labor history where the autonomous creative capacities of

working folks reached far beyond the capacities of union bureaucrats to

envision struggle towards fundamental change in workplace social relations.

Support remained strong in the Memphis community with national attention and

aid from the civil rights establishment arriving later.

This showed prominently in a community march that King

participated in. Police violently attacked some marchers and they fought back,

smashing up property in downtown Memphis in the ensuing clash. King was appalled that these marchers did

not follow his strict philosophy of nonviolence. However, some strikers and

community members felt his intervention was opportunist and aloof from

strategies and goals agreed among folks in Memphis. King’s actions and

attitudes were a telltale sign of how relations between the civil rights establishment,

supported by many labor bureaucrats in 1968, and rank-and-file workers as well

as community groups would operate in future labor struggles.

However this would not be the case. Some of the same black leaders in the civil rights establishment, who had sought to aid sanitation workers against racist Memphis city officials, would just nine years later be in the same position as Henry Loeb. By then they were willing to use the same strikebreaking tactics he had employed in his attempt to crush the 1968 strike. This complex relationship of class and race at the dawn of the era of black mayors and city officials, in their fight to contain the aspirations of community and workers self-management, comes into focus when we examine the 1977 Atlanta strike.

CLICK THIS LINK TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE

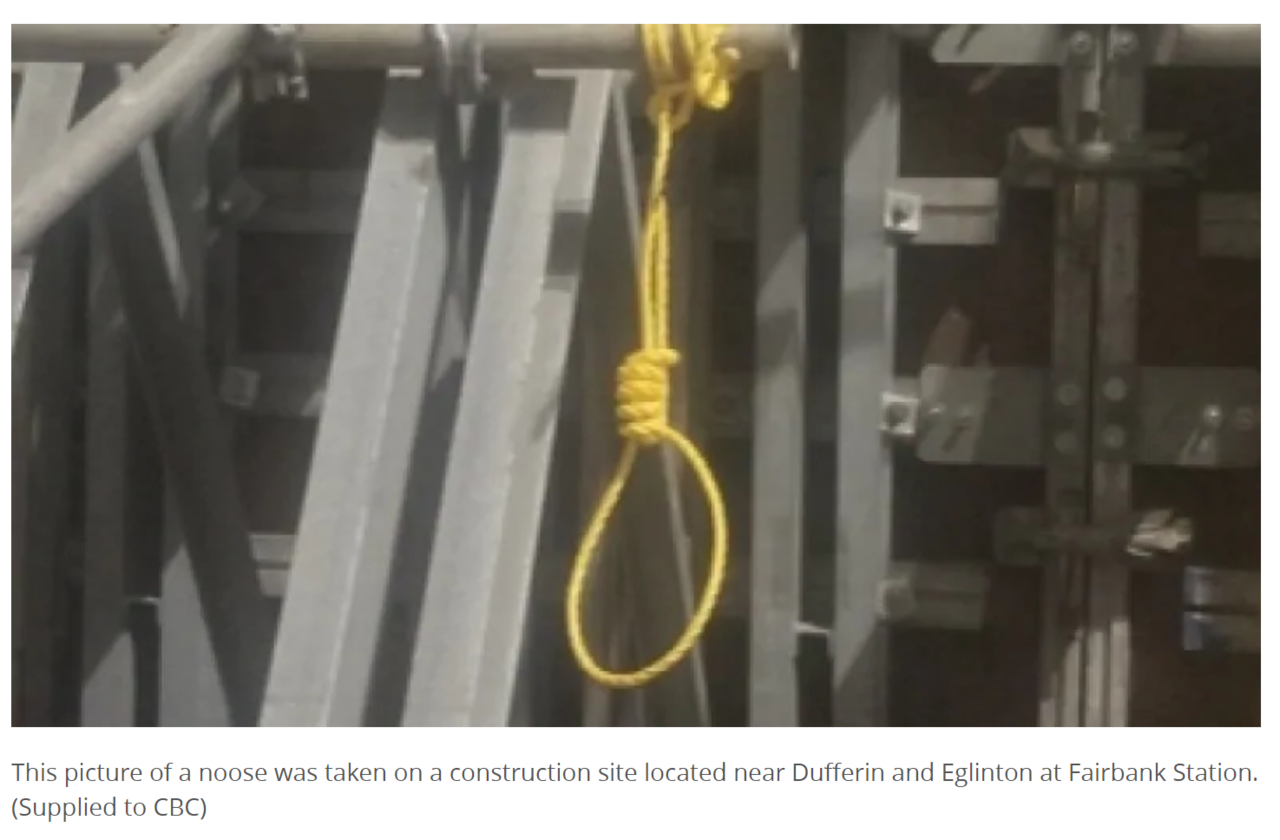

Carpenters’ Local 27 has reportedly requested and received

the resignation of one of its members in response to a noose being hung at a Crosslinx

Transit Solutions (CTS) worksite for a Metrolinx project. The noose was

allegedly placed with the intent of threatening and intimidating black tradesmen

working at the construction site.

The Carpenters’ statement read, “After a review of the

events that took place, severing this individual’s connection and membership

was the appropriate action; Local 27 denounces these acts in the strongest

terms, and supports our industry employer colleagues in their swift removal of

the individual. Behaviour that makes anyone feel unsafe on construction

worksites will not be tolerated, and accountability rests on everyone in the

industry to create safe and respectful workplaces.”

Ontario’s Minister of Transportation Caroline Mulroney previously reported on Twitter,“This is disgusting and unacceptable. I have spoken to the CEO @Metrolinx and the @TorontoPolice hate crime unit was called to investigate.” A Toronto Police Services spokesperson confirmed that a noose was found and that an investigation was underway.

For 140 years, the Carpenters Union has been a well-known

haven for unchecked racism, and a hornet’s nest for bigoted white & Hispanic

construction workers, according to many black union carpenters who have been

victimized by fellow members.

This racially charged anti-black attack was the fourth

reported incident of a noose being found at a Toronto construction site since

the beginning of June 2020.

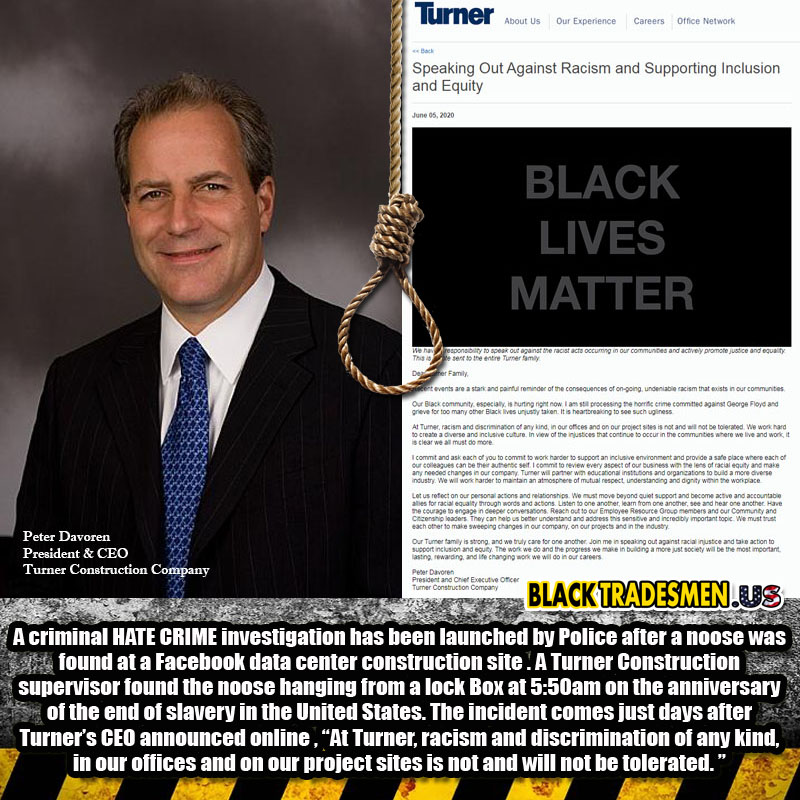

Construction on Facebook's billion-dollar facility in New Albany, OH was temporally put on hold after racist graffiti was discovered at the site. According Turners to all construction workers were then required to undergo what the industry calls ‘anti-bias’ training, trainings that in the past, have rendered little in stopping race based attacks on construction sites; attacks that have escalated in recent months coinciding with social & economic uprisings across the U.S.

A spokesman with Turner Construction Company, one of the

largest in the country, confirmed that the graffiti was found on the

construction site, and said that the company subsequently called the police and

shut down the site. But Turner refused to say what the graffiti entailed, or

where it was found. Turner says it is reviewing security footage to try and

find out who is responsible for the attack.

According to Columbus Business First, the $1.7 billion

Facebook campus is the largest construction project in Central Ohio. A data

center has already been completed and opened, and the third is under

construction. Two more buildings are planned as part of the campus. Turner says

that construction will resume once the training is complete.

A similar incident shut down Turner’s construction of the FC

Cincinatti stadium project the week before, when racist graffiti was discovered

at the future home of the FC Cincinnati soccer team. According to Turner this

incident also was reported to the police, and all staff was required to

participate in what many black tradesmen refer to as more “meaningless

anti-biased training.”

Black tradesmen and women have been under constant attack

this summer particularly hard, as these two graffiti incidents have not been

isolated, and are rather common; earlier this summer, nooses were found hanging

in several construction sites across the United States and Canada.

These hateful attacks have transpired during a summer when

the construction industry and the U.S., in general, have grappled with

systematic anti-Black racism, its prevalence, and how to remedy it. Turner and

other major construction firms across the U.S. announced this summer that they

would be taking a hard look at racism within the industry, but have not

announced any measures to identify and eliminate these racist elements that are

plaguing its workforce to the core. CHECK OUT OUR RELATED ARTICLE, THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY PLEDGES TO ELIMINATE RACISM, BUT WITHOUT A PLAN

While black construction workers across the U.S. seek to realize their dreams of succeeding as talented trade professionals, and builders of communities, these recent attacks show that they are constantly being dragged down by the inner workings of industry racists and bigoted unionist that seek to harass and intimidate black tradesmen and women.

The time has long come for construction labor unions and

non-union firms alike to finally stand up, and fulfill their duties as leaders

and protect their black workers, by taking all of their reports of racism,

discrimination, and harassment seriously, and eliminating known racist

agitators, and corrupt disingenuous supervisors that condone racist behaviors, the

very one’s that are corroding the reputation of the industry as a whole.

One way to combat these racist attacks is by doubling down

in the face of racism and adversity, by intentionally recruiting and training Tens-of-thousands

of future black construction workers, the U.S. so desperately needs. The act of building up the black construction workforce would help shift the scales of the

industry in favor of those workers that are most oppressed, and in need

of employment protections. Yet the industry in far to hesitate to act

appropriately and invest properly in this area.

The systematically racist Jim Crow era tactic of recruiting

black construction workers into faulty ‘one-and-done’ union programs, known in

the industry as ‘Pre-Apprenticeships,’ and other employment tricks such as non-union‘Temporary Day worker’ programs forces black apprentice, and unskilled

laborers to work for contractors for less, without union benefits, and substantive

training, is still in effect today and must end. These types of shady employment

practices are used throughout the industry, especially in the

black communities, where new construction development in often booming.

And with half of all black construction workers being card carrying union members, the construction trade unions and their umbrella group, the Building and Construction Trades Councils must acknowledge their important role as industry leaders and immediately release comprehensive data showing their exact number of black workers in each trade, so that an honest conversation can finally begin, and substantial changes can be made as to how black workers are properly recruited, trained, retained, and protected in the hostile environment of 2020.

Ravena, NY – A federal lawsuit filed by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) alleges that black tradesmen were subjected to harsh racial discrimination, harassment, intimidation, and an attempted noose snaring at the Lafarge Ravena Cement Plant by the Texas subcontractor CCC Group while the plant was undergoing a $300 million multiyear upgrade.

These vicious racially

based attacks continuously occurred over a nine-week period without

intervention, according to the black tradesmen mentioned in the suit

The lawsuit filed in U.S. district court contends the

following -

CCC Group, Inc., violated federal law when it fostered a work environment rife with racist comments and discriminatory work conditions, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) charged in a lawsuit filed.

The San Antonio, Texas-based construction company operated a

construction site in Ravena, N.Y., in 2016. According to the EEOC’s lawsuit,

white supervisors and employees regularly made unwelcome racist comments, used

racial slurs, threatened black employees with nooses, and subjected African

American employees to harsher working conditions than white co-workers.

The EEOC charges that white employees frequently referred to

black employees with insulting racial epithets. According to the EEOC’s

lawsuit, some of this harassment occurred on a company radio channel for all to

hear. White employees bragged that their ancestors had owned slaves and told a

black employee he walked funny because slaves used to walk with a bag on their

shoulder picking cotton.

Further, one white supervisor attempted to snare an employee

with a noose, the EEOC said. Another Caucasian supervisor told an African

American employee that for Halloween, “You don’t even have to dress up. I will

dress in white and put a noose around your neck and we’ll walk down the street

together.”

The EEOC further charges that African American employees

were given more physically taxing and dangerous work than Caucasian

counterparts, including being assigned outdoor work in winter while white

colleagues worked inside. Black employees objected to and complained about the

racial harassment, but it persisted, the EEOC said.

Such alleged conduct violates Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, which prohibits employers from discriminating against employees on

the basis of race. Race harassment is a form of race discrimination that is

prohibited by the statute.

The EEOC filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the

Northern District of New York, after first attempting to reach a pre-litigation

settlement through the agency’s conciliation process. The EEOC seeks

compensatory damages and punitive damages for the affected employees, and

injunctive relief to remedy and prevent future workplace racial harassment.

“Employers need to proactively prevent any behavior that

creates a racially hostile workplace,” said Jeffrey Burstein, regional attorney

for the EEOC’s New York District Office. “Here there were numerous examples of

abhorrent racial discrimination and harassment. The use of a noose is

especially vicious. Such misconduct violates federal law and common decency.”

Judy Keenan, acting director of the New York District Office,

added, “Racial harassment is never acceptable. This harassment was especially

vicious, widespread and continuous, and the employer failed to do anything to

stop it.”

The EEOC’s New York District Office is responsible for

processing discrimination charges, administrative enforcement, and the conduct

of agency litigation in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New

York, northern New Jersey, Rhode Island and Vermont. The agency’s Buffalo Local

Office conducted the investigation resulting in this lawsuit.

Lafarge Company who was contracted as the general contractor on

the project, issued the following statement, “We find the allegations against

CCC contracting to be very concerning.

Lafarge and its parent company, LafargeHolcim, take all claims of

discrimination of any kind very seriously. We follow a business code of conduct

and investigate and take action on all complaints that are brought to our

attention.”

For years black American men and women have been subjected

to the unreasonable approval of white employers, picking away at their black

identities in order to cuddle white-anglo insecurities in the workplace. This

specific type of attack on black working men and women can especially be seen

when whites determine what is considered to be a so-called professional hair

style, and what is not.

In the court of white society, any black person can make a

choice to have ‘locks’ aka ‘dreadlocks,’ but choosing to have them often means

accepting the very real probability of not getting hired for a job that you are

clearly qualified for. And in the construction industry, many black tradesmen

attribute this ‘ban on locks’ as a ‘buck breaking’ tool that hearkens back to

the days of American chattel slavery.

In today’s construction industry, some employers have

implemented rules against locks aka ‘Dreadlock bans’ which falls

disproportionately on black American workers, and carries historical racist

reproach for black people being their natural selves.

Drawing from unique styles of African cultural traditions, for

centuries black American descendants of slavery and their natural hair has been

both a case of pride and punishment from white society.

During the period of American Chattel slavery, enslaved black people took meticulous care of their African hairstyles, which served as a form of self-expression when they had little control over their own bodies while being kept in bondage for over 250 years, often helping do each other’s hair, sharing in a communal activity that continues today in American barbershops, salons, and homes.

In retaliation, white slave owners would often degrade African hair by referring to it as “wool,” and some slave owners would cut the hair of enslaved black people they deemed unruly, and completely shaved black women’s heads bald to castigate and demean them.

After the end of slavery, many black Americans began

attempting to alter and or hide the natural texture of their hair, using

chemical relaxers, hot combs, wigs, and weaves in order to mimic the appearance

of straight European hair, or to create hairstyles that were more pleasing to

white eyes.

Many of the old methods used to manipulate black peoples

natural hair remains in use today, but the cultural movements of the 1970s empowered

many black Americans to again embrace hairstyles that didn’t require them to

transform the texture of their natural hair, such as Afros, braids, twist, and locks.

After years of black protests against Jim Crow laws restricting employment of blacks, Congress eventually passed Title VII in 1964 to prevent employers from discriminating based on a person’s “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

But in the 2014 case of Chastity Jones, a black women who refused to be pressured into cutting her locks for employment, the court chose to ignore the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s (EEOC) reasoning that the “concept of race encompasses cultural characteristics related to race and ethnicity,” such as dreadlocks, which, it noted, are “common for black people and suitable for black hair texture,” and dismissed her claim of discrimination.

While the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires workers to cover and protect hair longer than four inches in certain settings to prevent it from getting caught in machine parts, making it clear that hair must be securely fastened with a bandanna, hair net, soft cap, durag or the like.

The Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit’s dangerously narrow view of equal protection under the law willfully ignored that systematic and individual acts of discrimination against black Americans is often based on both physiological and cultural attributes, associated with what white Americans arbitrarily deem acceptable for black people.

This type of state sponsored racist regulation governing

natural black hairstyles has emboldened some contractors and employers to

continue this widespread practice of not hiring and or firing black tradesmen

and women for having dreadlocks and other natural hairstyles that they deem

unprofessional, while allowing white and Hispanic workers to sport full

mullets, ponytails, and shaggy hairstyles at the detriment of black workers is further evidence that economic disparities and inequalities still exist for black

Americans to conform, or be locked out of economic opportunities.

We want to hear your story! Have you ever been fired or not hired due to your hairs length or style! If so email us at ourteam@blacktradesmen.us