Striking black sanitation workers vs. black officialdom in 1977 Atlanta Re-examined Part 1

This article is a

case study of the betrayal of the African American working class by the Black

political class elites brought to power by the Civil

Rights and Black Power movements of the 1960's.

"A disgrace

before God"

Labor struggle in

the American South has a long and proud tradition. From the historic

textile mill strikes of 1934, to streetcar workers in 1949 Atlanta, to

sanitation workers in Memphis and St. Petersburg, Florida in 1968, working

folks have organized to control social relations and conditions of labor in

their workplaces, and to regain a semblance of their own humanity in the face

of attacks from company bosses, police, and government officials. And this was

all initiated with little or no formal union infrastructure or support. Yet Southern labor history is portrayed as

backward or underdeveloped in relation to the North, with its long tradition of

unions in large industrial cities like New York, Detroit, and Chicago.

Instead we see that Southern folks, blacks and whites alike, have struggled for

years against bosses running company towns with an iron fist, against Jim Crow

segregation pervading workplaces, neighborhoods and cities, and against all

authoritarian forces viewing organized labor struggles as the coming terror.

Workplace organizing among sanitation workers, by 1977, had

a proud history. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, in places like New York City,

Cleveland, Atlanta, St. Petersburg, and most famously Memphis in 1968,

sanitation workers, as individuals and as organized groups, battled city bosses

against slave wages, unsafe working conditions, and for the right to form

unions and workplace associations on their own terms. These struggles went hand-in-hand with the black liberation movement,

for defeating white supremacy was a challenge met in neighborhoods and in

workplaces.

The city recognized the strikers’ call for union recognition, nationally backed by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) and conceded to demands for better pay and improved workplace conditions. This scene repeated itself in St. Petersburg and Cleveland later that year. This also occurred in Atlanta in 1970, where civil rights figures, some of whom were newly elected city officials, supported striking sanitation workers threatened with termination by Atlanta’s white mayor Sam Massell.

Fast-forward seven years to the Atlanta of 1977 and

something strange, one may think, happened. The script was flipped. The same

black officials who supported sanitation workers against firings by a white

mayor decided to replace striking city sanitation employees with scabs. This

occurred with the full support of many old guard civil rights leaders and

organizations, allied with business and civic groups associated with Atlanta’s

white power structure during Jim Crow segregation. What explains the apparent about-face by black officials?

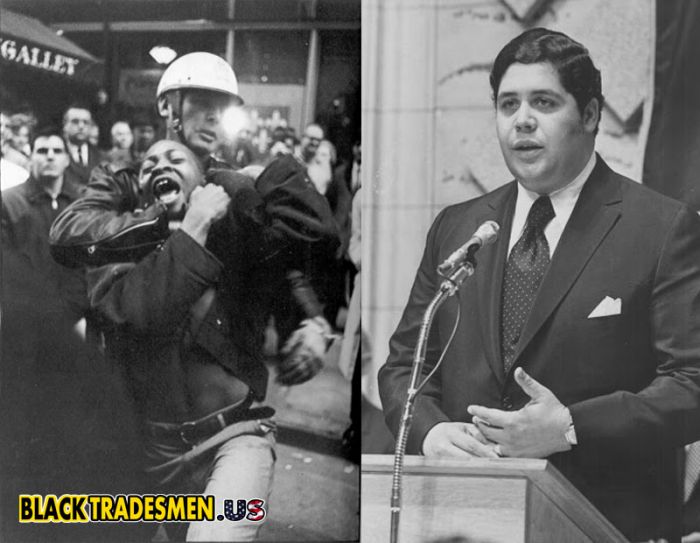

The Atlanta strike of 1977 shows the coming of age of a

coalition of black and white city officials, along with civic and business

elites, under the leadership of the city’s first black mayor, Maynard Jackson.

Just seven years earlier Jackson publicly sided with sanitation workers against

a white mayor seeking to fire them. Jackson and some members of the civil

rights establishment, in positions of local government by the mid 1970s, did

not hesitate to marshal the forces of official society against the

self-activity of black workers. They

allied with white business and civic elites, the same people that just a few

years earlier openly supported white supremacist segregation, all in the name

of smashing the sanitation workers’ strike by any means necessary.

The coalition of black and white elites 71 years later

helped foment class antagonisms that ultimately bubbled to the surface. The

difference from 1906 was blacks had a seat at the table of Atlanta city

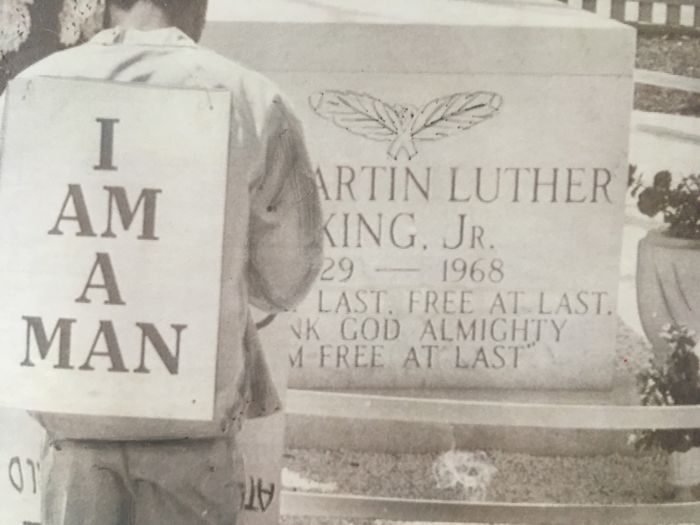

government. The demise of the 1977 sanitation strike appeared to be a blow to

the black liberation struggle of the 1960s and 1970s, showing that its mainly

reformist victories actually signaled a defeat of the broader movement towards

anti-racism and self-government. It signaled to working folks, black and white

alike, that the promised land Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of while addressing

sanitation workers in Memphis, just a day before he was assassinated, appeared

open only to business, political, and religious elites.

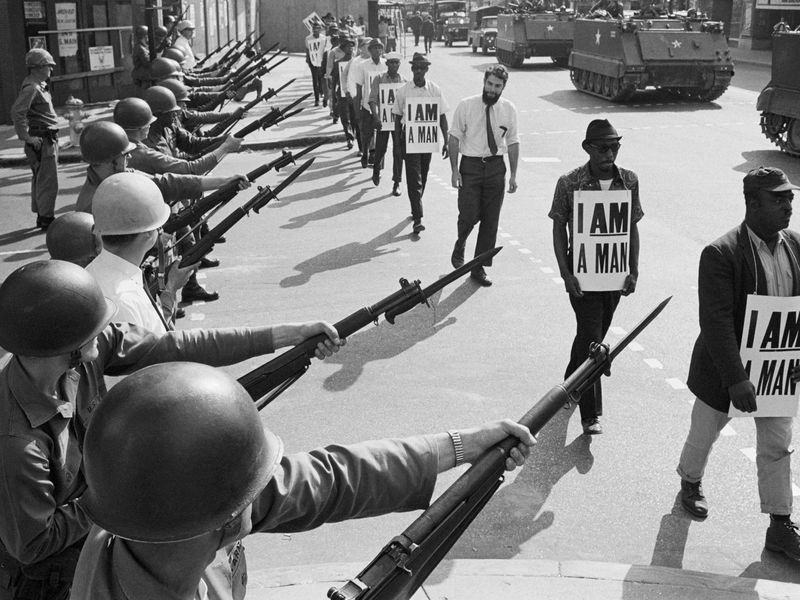

Memphis Sanitation

Workers Strike, 1968

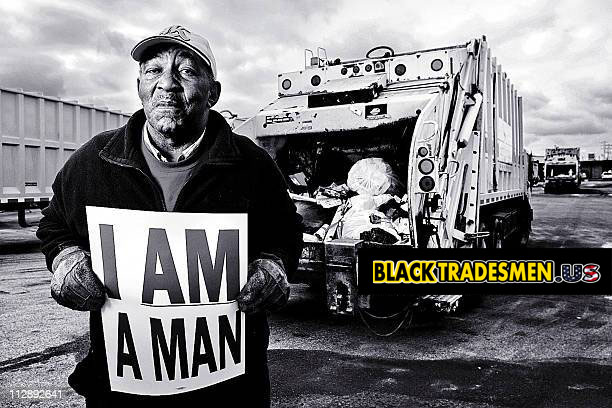

This was evident in the treatment of city sanitation

workers. This job, socially open only to black men, paid such menial wages that

most workers lived below the poverty line. After numerous attempts to create a

union to counter the city bosses and improve social and material workplace

conditions, sanitation workers finally struck in February 1968. What ultimately sparked the strike was the

death of two men crushed by faulty garbage trucks. With no formal union support

through the national AFSCME leadership, who initially told folks to stay on the

job, men organized a complete work stoppage, asking for significant

improvements in pay, work conditions, and the right to unionize.[2]

Led by Mayor Henry Loeb, Memphis city government took a firm

line against these individuals that would dare challenge the social, economic,

and racial divisions prevailing in Memphis. But it would be white supremacists

like Loeb and his ilk who would be left rotting on the trash heap of history by

the strike’s end in April 1968.

Unionization efforts

began a few years earlier, led within the ranks by T.O. Jones. For his

efforts, Jones was fired, but he continued working towards unionization as an

organizer for AFSCME Local 1733. By the cold winter of 1968, sanitation workers

were tired of workplace conditions, faulty equipment, and pay ranging from $1.65

to $1.85 an hour for laborers and $2.10 for truck drivers.[3] The attitude of

city officials was demeaning, telling employees that going on strike was

unnecessary and illegal. Besides, sanitation workers were lectured, the

benevolent white city fathers took care of them anyway. However a critical mass of sanitation workers, with strong support from

the community, had become sick and tired of the city’s plantation mentality

that saw them as nothing more than misbehaving children.

Striking workers countered by carrying signs proclaiming “I Am a Man.” It was not simply small

economic gains and improved workplace conditions motivating Memphis sanitation

men to organize collective labor action. Rather it was a call to change the

racist social and economic conditions black folks endured in Memphis. These

conditions had fundamentally not changed since the time of slavery. The new

society was breaking out of the old order where white supremacy had ruled

virtually unchecked.

At this historical moment of labor struggle by Memphis

sanitation workers, national leaders in AFSCME viewed their actions as

troublesome. When initially informed of

the walkout, AFSCME’s field service director P.J. Ciampa privately stated, “I need a strike in Memphis like I need a

hole in the head.” He also

chewed out T.O. Jones for helping start an illegal strike, though eventually

promised support from the national office.[4]

This was yet another

example in American labor history where the autonomous creative capacities of

working folks reached far beyond the capacities of union bureaucrats to

envision struggle towards fundamental change in workplace social relations.

Support remained strong in the Memphis community with national attention and

aid from the civil rights establishment arriving later.

This showed prominently in a community march that King

participated in. Police violently attacked some marchers and they fought back,

smashing up property in downtown Memphis in the ensuing clash. King was appalled that these marchers did

not follow his strict philosophy of nonviolence. However, some strikers and

community members felt his intervention was opportunist and aloof from

strategies and goals agreed among folks in Memphis. King’s actions and

attitudes were a telltale sign of how relations between the civil rights establishment,

supported by many labor bureaucrats in 1968, and rank-and-file workers as well

as community groups would operate in future labor struggles.

However this would not be the case. Some of the same black leaders in the civil rights establishment, who had sought to aid sanitation workers against racist Memphis city officials, would just nine years later be in the same position as Henry Loeb. By then they were willing to use the same strikebreaking tactics he had employed in his attempt to crush the 1968 strike. This complex relationship of class and race at the dawn of the era of black mayors and city officials, in their fight to contain the aspirations of community and workers self-management, comes into focus when we examine the 1977 Atlanta strike.

CLICK THIS LINK TO CONTINUE READING THIS ARTICLE