How Dreadlocks are locking black construction workers out of jobs

For years black American men and women have been subjected

to the unreasonable approval of white employers, picking away at their black

identities in order to cuddle white-anglo insecurities in the workplace. This

specific type of attack on black working men and women can especially be seen

when whites determine what is considered to be a so-called professional hair

style, and what is not.

In the court of white society, any black person can make a

choice to have ‘locks’ aka ‘dreadlocks,’ but choosing to have them often means

accepting the very real probability of not getting hired for a job that you are

clearly qualified for. And in the construction industry, many black tradesmen

attribute this ‘ban on locks’ as a ‘buck breaking’ tool that hearkens back to

the days of American chattel slavery.

In today’s construction industry, some employers have

implemented rules against locks aka ‘Dreadlock bans’ which falls

disproportionately on black American workers, and carries historical racist

reproach for black people being their natural selves.

Drawing from unique styles of African cultural traditions, for

centuries black American descendants of slavery and their natural hair has been

both a case of pride and punishment from white society.

During the period of American Chattel slavery, enslaved black people took meticulous care of their African hairstyles, which served as a form of self-expression when they had little control over their own bodies while being kept in bondage for over 250 years, often helping do each other’s hair, sharing in a communal activity that continues today in American barbershops, salons, and homes.

In retaliation, white slave owners would often degrade African hair by referring to it as “wool,” and some slave owners would cut the hair of enslaved black people they deemed unruly, and completely shaved black women’s heads bald to castigate and demean them.

After the end of slavery, many black Americans began

attempting to alter and or hide the natural texture of their hair, using

chemical relaxers, hot combs, wigs, and weaves in order to mimic the appearance

of straight European hair, or to create hairstyles that were more pleasing to

white eyes.

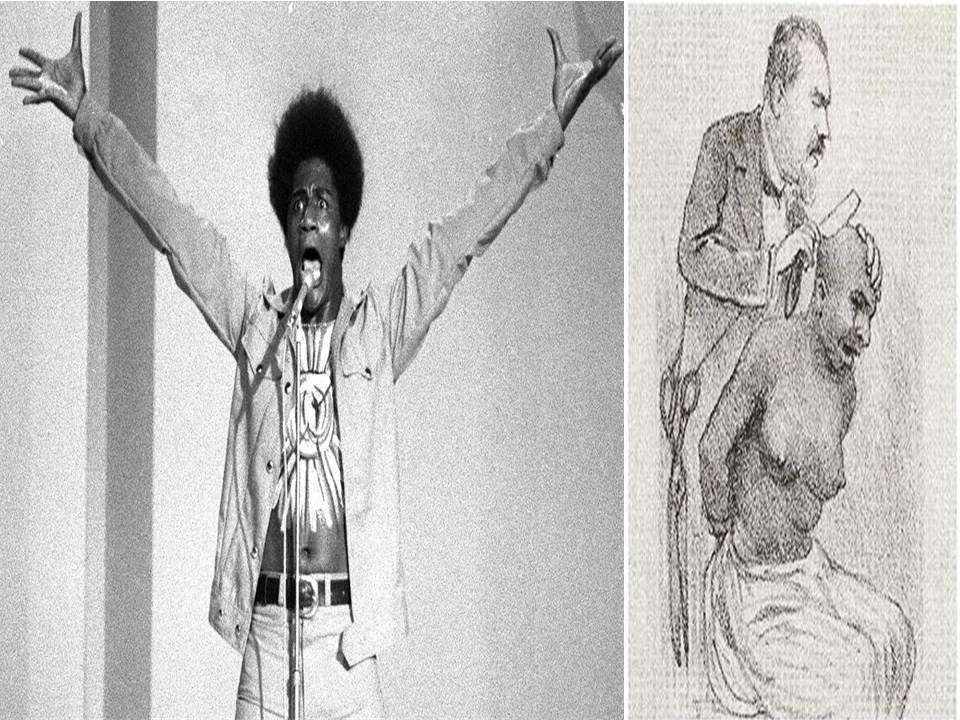

Many of the old methods used to manipulate black peoples

natural hair remains in use today, but the cultural movements of the 1970s empowered

many black Americans to again embrace hairstyles that didn’t require them to

transform the texture of their natural hair, such as Afros, braids, twist, and locks.

After years of black protests against Jim Crow laws restricting employment of blacks, Congress eventually passed Title VII in 1964 to prevent employers from discriminating based on a person’s “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

But in the 2014 case of Chastity Jones, a black women who refused to be pressured into cutting her locks for employment, the court chose to ignore the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s (EEOC) reasoning that the “concept of race encompasses cultural characteristics related to race and ethnicity,” such as dreadlocks, which, it noted, are “common for black people and suitable for black hair texture,” and dismissed her claim of discrimination.

While the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires workers to cover and protect hair longer than four inches in certain settings to prevent it from getting caught in machine parts, making it clear that hair must be securely fastened with a bandanna, hair net, soft cap, durag or the like.

The Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit’s dangerously narrow view of equal protection under the law willfully ignored that systematic and individual acts of discrimination against black Americans is often based on both physiological and cultural attributes, associated with what white Americans arbitrarily deem acceptable for black people.

This type of state sponsored racist regulation governing

natural black hairstyles has emboldened some contractors and employers to

continue this widespread practice of not hiring and or firing black tradesmen

and women for having dreadlocks and other natural hairstyles that they deem

unprofessional, while allowing white and Hispanic workers to sport full

mullets, ponytails, and shaggy hairstyles at the detriment of black workers is further evidence that economic disparities and inequalities still exist for black

Americans to conform, or be locked out of economic opportunities.

We want to hear your story! Have you ever been fired or not hired due to your hairs length or style! If so email us at ourteam@blacktradesmen.us