Remembering the black troops that built the most difficult/expensive project during WWII

The attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on December 7, 1941,

would bring the United States into World War II, but it also raised a concern

that the U.S. Territory of Alaska was vulnerable to Japanese attack. The Aleutian

Islands off southwest Alaska were closer to Japan than any point in North

America. In the event of a Japanese invasion, the Alaska-Canada highway (ALCAN) would be

necessary to protect Alaska civilians.

Overland travel by car, truck, or train between the United

States and the Alaskan territory at that time was just not possible due to the

rugged topography, and Canada did not have an incentive to build a connecting

road through its territory north of Dawson Creek.

So, in 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt along with the

Canadian government authorized the construction of the Alaska-Canada Highway

(ALCAN) to connect Alaska to the continental United States.

Construction of the highway begin on March 8, 1942, but, in order

for this highway to prove effective, the speed in which it was constructed was

essential to the military’s needs; the Alaska-Canada Highway needed to be built

in 8 months’ time.

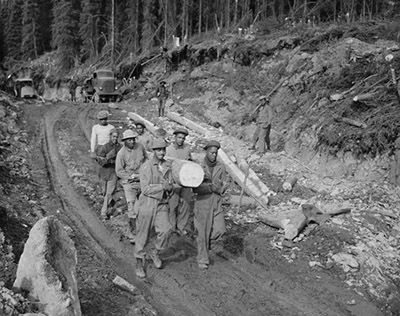

To complete this grueling highway in just 8 months, the U.S.

government hired private contractors and also commissioned the Army Corps of

Engineers. Due to World War II, many members of the Army Corps of Engineers

were in the South Pacific assisting with war efforts. This led to the need for

more manpower to complete the administration’s ambitious Alaska Highway

project. As a result, the War Department led by Colonel William M. Hoge, took

the historic step of deploying Black/African-American regiments of the Army Corps of

Engineers.

Approximately

5,000-7,000 of the initial 11,000 troops assembled to complete the highway and

install the companion Canol pipeline were Black. There were four regiments of

African-American engineers involved in building the Alaska-Canada Highway, the

93rd Engineer General Service Regiments, the 95th Engineer General

Service Regiments, the 97th Engineer General Service Regiment and the 388th

Engineer Battalion. Theirs were the first black regiments deployed outside the

lower 48 states during the war.

In the interest of speed, officials decided to build the

road in two phases. A pioneer road would be carved out of the difficult terrain

in 1942 to open the route for supply trucks by year's end. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was to build

the pioneer road, with Army engineering units and private contractors. Initially, the Army divided the 1,500-mile project into

five segments, with private contractors responsible for the portion from Whitehorse

to Big Delta, about 560 miles. But after proving to be a very difficult feat to

complete, the contractors work was extended by 100 miles to the east.

Since approval of the Selective Service Act of 1940, Black

American soldiers had been drafted into the Army on the same terms as whites,

but as Heath Twichell explained in his book on the Alaska Highway,

"Segregation's legacy of bigotry and prejudice severely limited the

possibilities" for the work they would do:

“As a result, relatively few black infantry, armor, or artillery

units were organized during World War II… In the end, black soldiers were assigned to

more than their share of units engaged in low-tech, high-sweat duties in the

Engineers and Quartermaster Corps. Although the Corps of Engineers put most of

its new black soldiers into general-purpose construction battalions and regiments,

shortages of heavy equipment sometimes resulted in the black units' being

issued fewer bulldozers and more shovels and wheelbarrows than the white units

got.”

Another touchy issue was where to station the new black

units. In the United States, military leaders felt they had to worry about the

impact of large numbers of young black soldiers on nearby civilian communities.”

[Northwest , p. 97-98]

The enlisted men, most of them from the South, faced racial

discrimination from white officers. The black soldiers were barred from

entering any towns for fears from white soldiers that they would procreate a “mongrel”

race with local women.

During the construction of the highway, the black American

soldiers endured winter conditions they had never experienced before, including

record low temperatures, the temperatures ranged from 90 degrees above zero in

summer to 70 degrees below zero during the winter. The black troops also had to fight swamps,

rivers, ice and cold, whiles battling the segregation with in their own corp.

Jim Sutton, a white American soldier who had worked on the highway project

alongside the blacks stated:

"They were up here when we got up here. We were put in barracks, wooden barracks, and we had stoves and everything. These poor black people were doing the same job as we were and they had them in tents. I didn't think that was really fair."

Housing wasn’t the only form of injustice the black soldiers

faced, but many times struggling through long difficult trips to reach the project

site with their equipment, the black American troops found that their best equipment

would be shifted to the white units.

Although, in practice the African-Americans were involved in many phases of construction, often never working with the white troops, but performed the more grueling labor intense work, while white troops sometimes less skilled, managed and directed. For this reason, many of the soldiers felt they were fighting two wars, one against the Axis (Japan, Germany and Italy) and a second against segregation.

After cutting an access road over Mentasta Pass from Slana

to Tok, the all black 97th Engineers battalion was used to perform the grueling work of speeding

the opening of the northernmost third of the Alaska Highway by helping the

private contractors and the 18th Engineers close the gap between Whitehorse and

Big Delta. Similarly, after opening a trail from Carcross to help the 340th

Engineers reach Teslin, another all black battalion of the 93rd Engineers

would start work on the pioneer road from that point toward Whitehorse, during

freezing conditions.

With private contractors and Army engineering units working on segments of the Alaska Highway, gaps began to close in August. By the end of September, only the most difficult sections, through eastern Alaska and the southwest corner of the Yukon, remained to be completed. [North to Alaska , p. 130]

The final gap was closed on October 29, 1942, south of Kluane Lake. Coates quoted Malcolm MacDonald, British high commissioner to Canada, on the final moments:

The final meeting between men working from the south and men working from the north was dramatic. They met head on in the forest. Corporal Refines Sims, Jr., a negro from Philadelphia [of the 97th Engineers] . . . was driving south with a bulldozer when he saw trees starting to topple over on him. Slamming his big vehicle into reverse he backed out just as another bulldozer driven by private Alfred Jalufka of Kennedy, Texas, broke through the underbrush. Jalufka had been forcing his bulldozer through the bush with such speed that his face was bloody from scratches of overhanging branches and limbs. That historic meeting between a negro corporal and white private on their respective bulldozers occurred 20 miles east of the Alaska-Yukon Boundary at a place called Beaver Creek. [North to Alaska , p, 130-131]

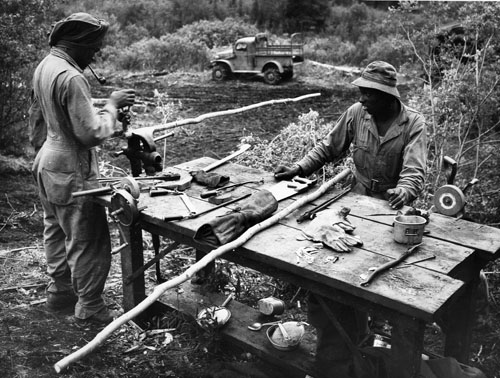

One of the greatest accomplishment of the black troops was Sikanni

Chief River Bridge. The Sikanni Chief River is a fast-moving river that is over

300 feet wide located about 162 miles outside of Dawson Creek, Canada. The

African-American engineers built the bridge without heavy equipment, utilizing

minimal supplies and in miserable conditions. They used hand tools, saws, and

axes to build the bridge in less than three days using lumber from nearby

trees.

During some phases of the bridges construction the black

troops had to plunge chest deep into the river’s freezing and rapidly moving

waters to set trestles. The soldiers used the headlights of trucks to keep

working at night while singing work chants and chain gang songs. Despite the

military still being segregated, after witnessing this amazing feat, Col. Heath Twichell Sr. ordered his white

officers to eat with the black enlisted men.

Over the years, as public attitudes changed, the

African-Americans who helped build the pioneer trail received recognition for

their accomplishment. Brinkley interviewed some of the veterans:

“They all talked to me about duty for country and reminisced about their harsh living conditions, tasteless food, and bitter winters where frostbite was their primary foe. Stories about wading chest deep into freezing lakes to erect bridge trestles or having a finger fall off when the temperature hit a record -70o F or lowering the coffin of a comrade into the cold ground conjured bleak memories of Jack London's most brutal tales like "To Build a Fire" or "Burning Sun." Snowdrifts were often twenty feet deep. "For months on end, I couldn't get a real night's sleep," one veteran recalled. "I had nightmares I was freezing to death." Although these black soldiers had at their disposal 11,107 pieces of equipment, trucks, tractors, crushers, graders, and bulldozers, breakdowns occurred hourly. The job was daunting. Never before, it seems, had so many survey sticks been hammered into the earth at a given time. To keep morale up they often chanted old southern work tunes like "Steel-Driving Song" and "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot." With brawn and courage and valor they persevered, completing the Alcan Highway in just over eight months, with the official opening on 21 November 1942. [Alcan , p. 10]

The African-American regiments that built the Alaska-Canada

Highway established a reputation for excellence especially in the field of

bridge building. However, their accomplishments were consistently ignored by

mainstream media and press. It took decades for them to receive proper

recognition for their achievements. Some say they were as “legendary” as the

Tuskegee Airmen and the Buffalo Soldiers.

Many people attribute the success of these African-American

engineers during the Alaska-Canada Highway project as one of the events that

led to eventual desegregation of the military in 1948. Some call the ALCAN

Highway the “Road to Civil Rights” for this reason.

After just over 8 months , the Alaska-Canada Highway (ALCAN)

was completed on November 21, 1942. The ALCAN highway project is still

considered one of the biggest and most difficult construction projects ever

completed by the US Army Corps of Engineers. It stretches 1,422 miles from

Dawson Creek, British Columbia in Canada to Big Delta, Alaska. The project cost

about $138 million dollars and was the most expensive World War II construction

project.

Approximately 30 men died during the Alaska-Canada Highway construction project. In 1992 there were over 2,000 different celebrations held to commemorate the highway's 50th anniversary, but none of them honored, and most hardly mentioned, the black units who represented one of the projects largest portions of manpower. James Eaton, curator of the Black Archives Research Center and Museum at Florida A&M University in Tallahassee, called the soldiers, "A lost page in history."

On July 4, 1992, the city of Anchorage, Alaska invited several of the veteran black troops from the corp. of engineers to participate in the city's parade down Main Street. Two of them, Albert E. France andDonald W. Nolan, Sr., were from Baltimore. France was a 75-year old retired railroad worker, while Nolan was a 72-year old retired postal worker, both recalled in a newspaper interview, the first thing they remembered from working on the Alaska-Canada Highway was the cold:

"It was awful

cold and it snowed for days," recalled Mr.France . . . . It was the

coldest winder on record in the territory.

"Leather would freeze," recalled Mr. Nolan . . . .

"We'd take galoshes, rubber galoshes - we called them 'Arctics' - and we'd

wear three, four pairs of socks we would double up on pants. We slept on the round

in pup tents."

“Food was never plentiful. C-rations, bittersweet chocolate

and "hardcracks" might be all a soldier would get to eat after the

harsh climate cut off supply routes.”

"We'd kill a bear, a huge black bear," said Mr.

Nolan,"about 9, 10 feet high, and those chops were delicious."

When the snow stopped, the rains started and the rivers swelled.

In summer, mosquitoes droned like airplanes and the "muskeg," a

uniquely Alaskan bog, swallowed tractors… In that barren landscape, the

off-work hours could seem exceptionally long.

Looking back, Nolan said he was glad to have served on the project. "You have something to tell your kids." [The Baltimore Sun , July 4, 1992]

Memorials for the black soldiers that helped in the competition

of the ALCAN Highway are scattered along

the highways 1,400 miles path. One of the most recognized memorials is the‘Black

Veterans Memorial Bridge’ which was dedicated in 1993 to the African-American

engineers who died during the construction project.

Congress in 2005 said that the wartime service of the four

regiments covered here contributed to the eventual desegregation of the Armed

Forces.