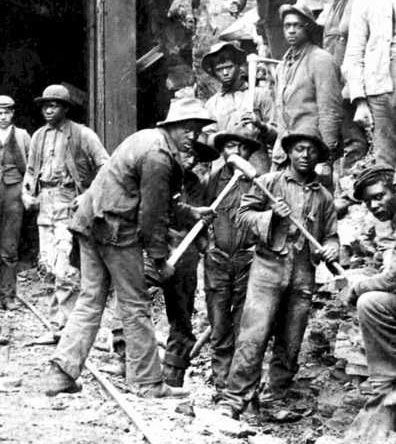

BLACK LABOR BUILT SOUTHERN U.S. INFRASTRUCTURE FOR FREE

To understand the historic growth of the American economy, you must understand that it’s growth was completely spearheaded by the free labor provided by black American slaves. While all slaves were assigned some non-agricultural tasks, a sizable amount were highly skilled and specialized.

In

the United States, about one-third of all male slaves and about one-quarter of

all female slaves were employed in occupations other than common field labor.

Among male slaves some estimate more than 35% were skilled and semiskilled

artisans, and tradesmen working directly on private and public construction

projects.

When examining the history of the U.S. economy prior to the Civil War, you must understand the South. The Southern United States infrastructure, primarily the Appalachian Mountainous Region, made it possible to fully integrate the south into the national economy. Because of the Souths ability to develop a strong infrastructure, it became deeply invested and relied upon by world markets.

This region of southern states was mainly incorporated in the production of raw materials, such as

logs, lumber, iron, coal, and also agricultural products and commodities. Through the use of slave labor, Appalachian agricultural producers, factories,

and mining companies exported their goods to the northeastern states and to Western

Europe for huge profits.

Appalachian plantations provided the mass majority of the black labor used to fuel economic growth in the Southern United States. To achieve the highest level of production from their slaves, Appalachian slave owners structured a system among their slaves to develop master/elite skilled tradesmen and laborers.

Appalachian slaves were skilled industrial and

commercial laborers 1.3 times more often than other U.S. slaves, but they were

also 3 times more likely to become “Drivers,” the top management position to

which slaves were appointed. Moreover, 30% or more of Appalachia’s slaves were

employed full time as literate industrial laborers in mostly non-agricultural

enterprise.

By 1860, nearly one-quarter of the Appalachian population was concentrated in towns, villages, and hamlets, and black Appalachians formed a significant component of the commercial labor force that resided in those small urban areas.

Black Appalachians supplied labor for

public works projects, but also supplied skilled labor for retail enterprises & developments, for home and

hotel construction, for artisan shops, and for construction companies across

the entire southern region of the United States. They provided some of the highest levels of craftsmanship recorded.

In towns located in the Appalachian counties of Alabama and Georgia, slaves and free blacks accounted for nearly half the population. Even in the region’s smaller villages – like Richmond, Kentucky, or Martinsburg, West Virginia, or Franklin, North Carolina; one-quarter to one-third of the residents were black Appalachians.

Black people who were free from slavery

formed small communities within Appalachian towns, and lived very meager lives,

living in small homes, or homeless in alleyways. But, because black labor was a

“valuable labor supply,” several Loudoun County, Virginia, merchants and companies

petitioned the state legislature for relief from the law requiring emancipated slaves

to “leave the state immediately.”

Because of the frequent presence of large amounts of unemployed freed black skilled workers, men were often “seen every day of the week standing on street corners, seeking day labor.”

Black codes to regulate the behaviors and

employment of freed blacks were developed. Under these laws blacks were forbidden to stand,

smoke, or spit on sidewalks, empty kitchen slops in public areas, to dance or

run in the streets, to utter profanity publicly, to collect money in public, to

ride in licensed vehicles, or to ride abroad after 7:30pm, this was known as “Black Curfew.”

Moreover, city ordinances specified the circumstances under which free blacks and slaves could engage in labor & trade. These laws were passed to justify the re-enslavement of free blacks so that their labor could be used to build state and local projects, or in agriculture.

State and local laws also “criminalized” poverty, and vagrancy was prohibited. Under these repressive laws, unemployed free blacks were subject to arrest and indenturement {Free labor}.

Throughout the south, the majority of public works were constructed by blacks. Without the modern power tools & equipment we use today, constructing and maintain buildings, and public spaces in the 1800's was in most cases a grueling task, thus slaves graded, paved, and cleaned streets, built bridges, built courthouse, built schools, maintained canals and sewers, collected garbage, and fought fires.

Like other urban centers, Appalachian towns also employed black slaves on public works and in public services. Slaves provided most of the labor to construct courthouses in McDowell, Cherokee, Watauga, Macon, Henderson Counties and the university buildings in Blue Ridge Virginia.

It was recorded that, after one Virginia

slave burned down his master’s barn “containing about 1500 lbs. of tobacco,

straw, and shucks of corn & oats” the court sentenced him to lifetime labor

on public works projects in the towns and villages of Nelson County.

In all eight Southern states where Appalachian counties were located, laws permitted county sheriffs to force runaway slaves in their custody to perform labor of public works projects, which they fully employed. For example, the towns of Roanoke and Charlottesville in Virginia and McMinnville and Knoxville in Tennessee used black convicts or hired slaves, paying their masters, for all kinds of public labor for their cities & towns.

The city of Knoxville, Tennessee hired slaves, paying their masters $10 monthly to fight fires, collect garbage, and handle other public services. Slaves forcibly manned the so-called “volunteer” fire company at Lexington, Virginia.

Charleston, West Virginia, and other river towns paid free black to light lanterns around the landings. Free black men who lived in the nearby houses were paid for lighting them every night and outing them out every morning. In Blue Ridge Virginia, enslaved and free blacks worked as “Mailboys” to deliver mail between towns and outlying rural areas.

While huge amounts of public works projects were being

performed by highly skilled slave labor and freed blacks, Appalachian slave

owners wanted to increase the lifetime value of their laborers, so they begin

to contract out children to learn trade skills. Slave owners employed child

slave labor to perform alongside their fathers as well as strangers. When they

were adults they could be leased out at higher rates.

Several American slave owners would regularly lease out

young male black slaves to towns as carpenters. Slave owners would often lease

children of slaves out to nonslaveholders. In this way, James Pennington and

his brother, both black American slaves, learned several trades through their

successive hires to a pump-maker, a stone-mason, a blacksmith, and a carpenter.

Another example is Darst and Jordan, a Rockbridge County

construction company, built large homes for slaveholders, and nonslaveholders,

they also undertook public works projects. Because this company relied solely

on a large slave labor force, the company regularly published newspaper

advertisements warning white towns people not to distract them from their grueling

construction labor.

Black slave laborers, tradesmen, craftworkers were extremely valuable to their owners. Slave owner who did lease out their black labor force

to public projects demanded top dollar from contractors. When the Muscle Shoals

Canal was being constructed in Tennessee, contractors gave special compensation

to the owners of slaves who were injured or killed by explosions or cave-ins.

White workers at that time were not covered by any type of accident insurance.

After hundreds of years of forced labor on many of the

United States public works projects, by black men,

women, and children, across

the South, opposition, and complaints of “unfair competition” by white labor

begin to arise. Most highly skilled construction positions & trades were now being claimed by whites, and white labor developed a bitterness that most

times led to violence against the slaves who had no part in the creation of the

system.

Since newly freed black tradesmen were highly skilled and could now compete for jobs in the free market, white workers, sometimes less skilled felt extremely threatened. White workers began protesting against the hiring out of skilled slaves as artisans, and tradesmen, as a way to keep the wages for themselves.

Soon after protesting against black labor in the free market, white working class people begin to commit many violent, and vile acts against poor working black

families and even those that were still in bondage, and considered as legal private property. These acts of violence

almost always were followed by laws that were passed to limit the employment, and use of

black labor on public works projects. Many states begin to pass laws that also prevented or made it very difficult for black American descendants of slaves to obtain contractors licenses, or become licensed architects. Many labor unions were also formed to stop the black labor class from working on public works projects all together.