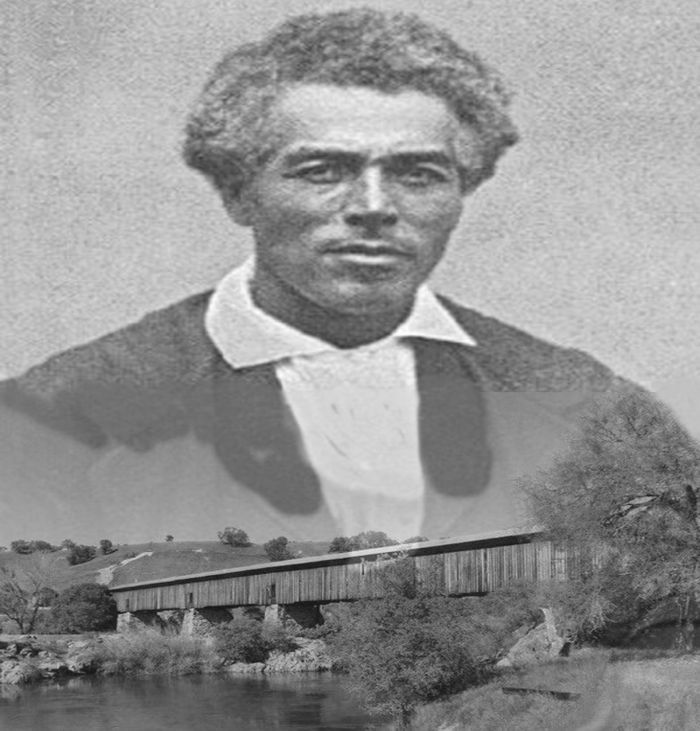

Remembering Horace King, ex-slave, Master Bridge Builder

Alabama Heritage - Information on Horace King's early years is scanty. He was born a slave in the Chesterfield District of South Carolina on September 8, 1807. His father was a mulatto named Edmund King; his mother, Susan (or Lucky), was the daughter of a full-blooded Catawba Indian and a black female slave. In the winter of 1829, Horace King's master died, and King and his mother became the property of John Godwin, a South Carolina house builder and bridge contractor.

Apparently, from the beginning of their relationship, King

was more of a junior partner in Godwin's company than a slave. Godwin developed

proposals; King supervised construction. With the success of the Columbus

crossing, known first as City Bridge and later as the Dillingham Bridge (pages

35 and 46), Godwin began to bid on and win other contracts for covered bridges

across the Chattahoochee. He and King built a 540-foot-long bridge south of

Columbus at Irwinton (now Eufaula), Alabama, for $22,000 (page 40). They

constructed a bridge at West Point, Georgia, in 1838-39; they built another at

Tallassee, Alabama, and they may have built another at Florence, Alabama, in

1839.

Because of the superior workmanship on the bridges King

supervised, Godwin was able to guarantee his bridges for five years, even

against floods. And when flood-related damage did occur, Godwin took full

responsibility. The flood of February and March 1841, known as the

"Harrison Freshet" (named for the ninth president of the United

States, William Henry Harrison, who died of pneumonia in April· of that year),

destroyed a portion of the bridge south of Columbus at Florence, Georgia, and

swept away almost the entire City Bridge in Columbus. Godwin repaired both

spans quickly. The Florence bridge was reopened to traffic by mid-April of that

same year, and Godwin rebuilt the City Bridge within only five months. Horace King's

skill and ingenuity made these feats possible.

In addition to building bridges, King probably also worked

on the important houses that the Godwin firm built around Girard and Columbus

during the 1830s and 1840s. Perhaps he supervised the slave workmen said to

have remodeled U.S. Senator Seaborn Jones' home, "Eldorado."

Certainly King worked for Jones, who hired him to build City Mills north of

Fourteenth Street in Columbus. King also worked on the Muscogee County

Courthouse (1838) in Columbus, and the Russell County Courthouse (1841) in

Crawford, Alabama. And he continued to build bridges for Godwin.

King's precise contribution to the design modifications

evident over the years in God win's bridges can only be speculated upon. The

bridges King supervised contained additional intermediate chords, a feature

that strengthened the trusses against twisting with age (Town himself had tried

to correct this problem by doubling the number of web members). Some of King's

bridges contained pier foundations formed by combining sand with timbers of

heart pine. Also improved over time were the procedures King employed in

erecting or assembling-without power machinery-vast trusses over water. Whether

or not King was responsible for these innovations, he was certainly responsible

for the care and efficiency with which these structures were erected. Indeed,

King's ability to supervise massive construction projects and to elicit

superior workmanship from mixed gangs of laborers, both slave and free,

impressed some of the most successful businessmen in the South.

One of these men was Robert Jemison, Jr., of Tuscaloosa, a lawyer and state senator, a prosperous planter, and the owner of a large and well organized network of interrelated businesses, including a stagecoach line, a turnpike and bridge company, and extensive saw mill operations. In the early 1840s, Jemison began contracting with Godwin for bridges in west Alabama, coordinating the contracts so that his mills supplied lumber for the projects while Godwin furnished the carpenters. Horace King supervised construction. After several joint ventures with Godwin and King, Jemison wrote to Godwin in 1845: "Please to add another testimonial to the style and dispatch with which [Horace King] has done his work as well as the manner in which he has conducted himself."

The next decades were particularly productive for King. He built

a bridge across the Flint River at Albany, Georgia, as well as a bridge house

that functioned as a portal to the span. That project, completed in 1858, had

been the special interest of Albany entrepreneur Nelson Tift, an energetic and

inventive businessman interested in developing south Georgia's economic

resources. Having failed to interest either the city or the county in his

bridge-building idea, Tift decided to undertake the project himself. To oversee

construction he hired Horace King. At the time, King was preparing to build a

bridge over the Oconee River near Milledgeville. He had already cut timbers at

the site when a disagreement over terms arose between King and his employers in

the Milledgeville area. Unable to resolve the disagreement, King shipped the

cut timbers by rail to Albany, thus becoming perhaps the first builder in the

South to prefabricate a major structure and ship it to the construction site.

As a free man, King also continued to work with Jemison on a

variety of projects. Jemison, a member of the state house ways and means

committee, may have helped King secure work on the second Montgomery

statehouse, constructed in 1850-51. Jemison and King bid on construction for

Madison Hall, a dormitory at the University of Alabama, but did not get the

bid. Jemison also consulted with King during one of the most massive

construction projects undertaken in antebellum Alabama-the building of the

Alabama Insane Hospital (Bryce) in Tuscaloosa, completed in 1860.

During the 1850s, John Godwin's fortunes continued to decline, primarily because of the failure of the Girard-Mobile Railroad in which Godwin had invested heavily. When Godwin died in 1859, his estate was insolvent, although the family still owned their large sawmill operation in Girard. The Godwin children, worried that King could be held accountable for their father's debts, took one further step to ensure his freedom by formally recording in the Russell County Courthouse that "the said Horace King is duly emancipated and freed from all claims held by us."

In the 1870s, the family moved from Alabama to LaGrange, Georgia. The reasons for the move are unclear. Perhaps John Thomas had decided that business prospects were better there. Or, perhaps the move had something to do with Horace King's interest in the work of the Freedmen's Bureau, the federal agency established to help safeguard blacks from any form of re-enslavement. Education for blacks had long been a concern of King and his eldest son, who believed in the old axiom, "Ignorance breeds poverty." Horace King hoped to establish a "small colony'' in Coweta or Carroll County, Georgia, where former slaves, both men and women, could study. It was not intended to be a utopian community, but simply a school designed to teach men trades and women "the domestic arts." Records indicate that the idea was blessed by Brigadier General Wager T. Swayne, assistant commissioner of the Freedmen's Bureau for Alabama, and by his superior, Colonel C. C. Sibley, Assistant Commissioner, District of Georgia, but no records have been discovered that tell us whether or not the colony was established.

Throughout the 1870s, the King Brothers' construction firm

continued to prosper, building a new chapel for the Southern Female College

(1875-76) at LaGrange, Georgia; King himself laid the cornerstone and spoke

from the platform at the accompanying ceremonies. They also built LaGrange

Academy (c. 1875), that city's first black school, as well as the Warren Chapel

Methodist Church and parsonage (c. 1875), also in LaGrange. CLICK HERE TO READ ENTIRE ARTICLE