How a Brooklyn protest brought change to the historically racist construction industry

In 1963, the failure of mainstream civil rights groups to negotiate

a workable plan for desegregating the construction industry inspired more

militant activists to increase pressure on mayors and union leaders of the

building trades unions across the United States.

In New York City, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) led

the way, taking the streets in Harlem to demand that the construction industry

immediately hire qualified African-American construction workers. In the summer

of 1963, 150 demonstrators shut down work at the Harlem Hospital annex.

Protesters blocked entrances to the work site and forced police to remove them

from the site. Several scuffles broke out, forcing the head contractor to

suspend work for the day. The following day more protesters arrived and fears

of a riot eventually brought more than 300 police officers to the construction

site.

While tensions mounted at the in Harlem, the mayor at the

time, Robert F. Wagner attended a conference in Hawaii. In his absence, Paul

Screvane, the acting mayor, officially shut down the Harlem Hospital project.

Protesters cheered when they heard Screvane’s decision. Screvane suspended work

on the hospital until the mayor could confer with labor leaders and investigate

the demonstrators’ charges.

As a result, the Harlem Hospital demonstration made fighting

against racial discrimination in the building trades the most important civil

rights issue in New York City. Other demonstrations sprang up all over the

city, and a coalition of activists from different organizations began a

round-the-clock sit-in at the mayor’s and governor’s offices. Calling

themselves the ‘Joint Committee for Equality’ they demanded that New York

elected officials enforce the state’s anti-discrimination laws, especially in

the building trades.

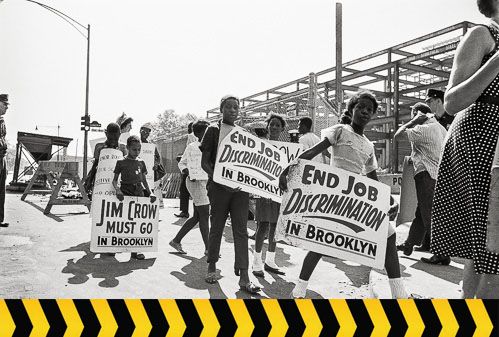

In Brooklyn, CORE activists wanted to build on the momentum

generated by the Harlem Hospital demonstration. Their target was the Downstate

Medical Center construction project slated by the state of New York to upgrade

the Kings County Hospital complex with a new 350-bed teaching hospital and

renovations to the State University of New York (SUNY) medical school campus housed

on the same property. These projects were part of the $353 million earmarked by

the state in 1960 to expand the entire SUNY system by 1965. Upgrading the two

state medical schools was the main priority of State.

The massive, multi-million dollar, state-funded Downstate

Medical Center project seemed to be a win for everyone invested, the SUNY

system, Kings County, and the residents who wanted affordable medical school

training. But one group that criticized the construction project was

unemployed black construction workers,

especially those that lived in the black residential areas of north central

Brooklyn, which bordered the area which the Downstate project was located.

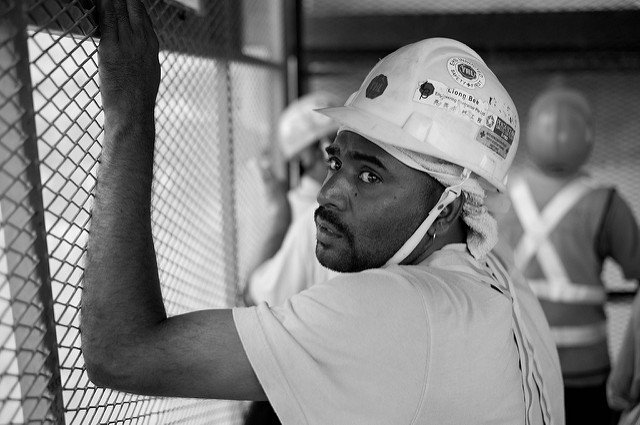

Brooklyn CORE activists found that except for a handful of

Carpenters’ Assistants, there were few black workers; the workforce for the

Downstate project was almost entirely white. Most of the workers came from

white areas of Brooklyn and Queens, but some commuted to the Downstate project

as far away as Long Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey. Yet black construction

workers could not attain jobs, although they lived just a quarter-mile from the

project.

Four leaders in Brooklyn CORE investigated the construction

site, and quickly realized that staging a demonstration at the Downstate

project would be difficult. The main work site was a seven-story medical facility

embedded in a sprawling complex four city blocks wide and one large city block

long. If Brooklyn CORE wanted to stage an effective protest and disrupt

construction at the project, they would need hundreds of participants. As a

result, its leaders sought support from other local civil rights organizations

and black churches.

Knowing that something needed to be done, Brooklyn CORE’s president

Oliver Leeds, contacted Warren Bunn, president of the Brooklyn chapter of the NAACP,

and John Parham, leader of the local Urban League chapter. In early July, the

three men went to the Downstate construction site to gather more data. Leeds,

Bunn, and Parham then took their complaints to leaders of local construction

unions and tried to convince them to recruit more black workers. The union

leaders’ responses were not pleasant. “They wouldn’t listen to us,” Leeds

recalled. “One of them almost threw us down the stairs.”

The three men went back to the Downstate project and planned

their demonstration strategy. They realized a large picket line in front of the

main entrance could effectively slow down the work site, and if enough people

sat down in front of the entrance, blocking trucks, they could repeat the

success of the Harlem protest. But Leeds knew Bunn and Parham could not rally enough

members to pull off that type of disruption. Demonstrators would have to

maintain the picket line from 7am to 4pm, five days a week. It would take

hundreds, if not thousands of people.

To find the people needed to successful picket the Downstate

project Oliver Leeds had the foresight to reach out to the black churches in

Brooklyn, several of which had over 1,000 members. But getting the ministers to

support a Brooklyn CORE project was its own struggle. For the most part, black

church leaders in Brooklyn held conservative views about civil disobedience.

Most prominent ministers did not want to risk their reputation by being

associated with Brooklyn CORE, and its protest, which tended to be

confrontational.

Most black ministers in Brooklyn at the time thought of

themselves as moderate power brokers, and had met with the mayor and governor on

several occasions, and some were appointed to government offices. The ministers

had traditionally used their influence over thousands of black voters as

leverage with elected officials. They felt they could lose their clout in City

Hall and in the Capital, if they participated in anything led by CORE.

But, many factors

changed the ministers hearts. According to Clarence Taylor, a historian, the Brooklyn

ministers inspired by the example of Martin Luther King, whose leadership in

the South motivated clergymen around the country to take direct action and

fight for social and political change. Confident they could get thousands of

their members to participate in the CORE protest at Downstate, they formed the ‘Ministers’

Committee for Job Opportunities’ and positioned themselves as the de facto

leaders of the campaign.

DIRECT ACTION at Downstate!

Impatient and bold, and not wanting to feel controlled by

the ministers, Brooklyn CORE members organized and began to picket the

Downstate construction site five days before the ministers arrived. On July 10th,

at 7am CORE amassed 30 members, along with their children, to block the entrance

to the work site, but failed to disrupt the site. This effort resulted in several

protesters being arrested when they sat down in front of an on-coming truck.

After getting news of the arrest at the Downstate

construction site, the Brooklyn ministers felt that their leadership could

control the picket line and keep the protesters from becoming too brash. On July 15th, they effectively took over as leaders of the Downstate campaign.

Still the demonstration attracted protesters who were neither interested in

following the minister’s directions nor willing to adhere to to the CORE principles

of nonviolence. These new protesters, more that Brooklyn CORE and the ministers’

moral authority and political power, proved to be instrumental in shaping the

outcome of the campaign.

For the most part, the ministers held rallies in their

church halls, raised bail money from members, and inspired congregants with

weekly sermons on the righteousness and justness of the Downstate construction

site protest.

Still, the Brooklyn CORE members were a significant force at

the picket line. Their experience during earlier campaigns made them much more

experienced than the ministers in working with the press and devising tactics

to disrupt the work site.

The ministers, on the other hand, were overly cautious when

it came to disrupting work at the site. Protective of their reputation, they

tried to choreograph their every move on the picket line, including the exact

day they would get arrested. The ministers planned to make their presence known

by giving interviews to reporters, and posing for pictures. They even sought to

control the demonstrators’ behaviors, a task that became more difficult as time

went on.

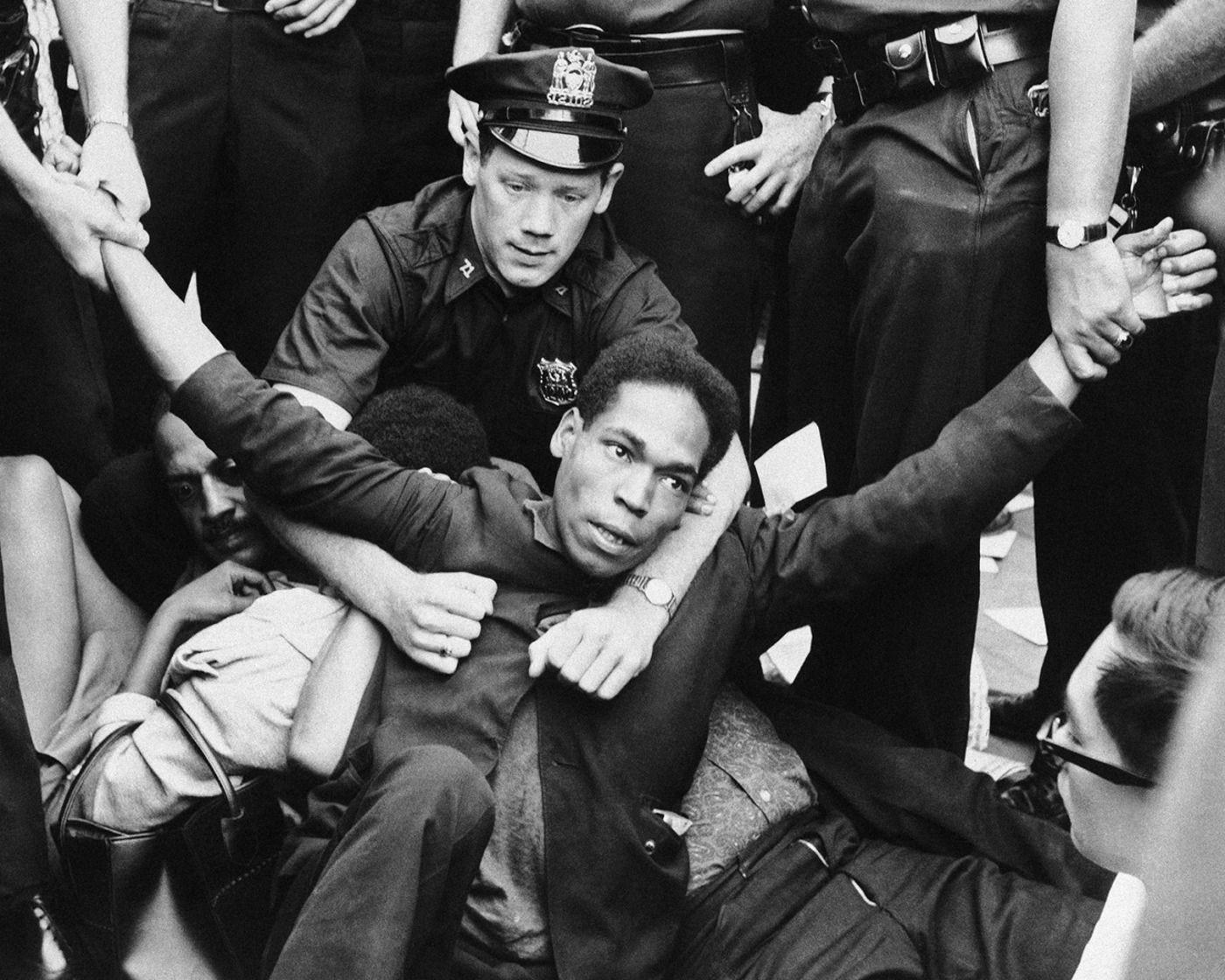

Media attention would be essential for the success of the

campaign, The CORE leaders and the ministers wanted photographers and

television cameras to capture images of demonstrators lying in front of trucks,

blocking entrances, singing freedom songs, and being carried away by police

officers, to rouse public support for increased employment opportunities for

African-American workers on publicly funded construction projects.

A rally held on Sunday, July 21st 1963, in Tompkins Park drew over 6,000

people. Reverend Sandy Ray declared that the Downstate campaign was a part of

the national struggle for civil rights and human dignity, “We are here in

response to the call of history,” he exclaimed. “There will be no turning back

until people in high in places correct the wrongs of the nation.” Reverend Dr.

Gardner Taylor shouted, “We’re ready!” he added, “We’re not going another step

and America is not going anywhere without us!””Revolution has come to Brooklyn!”

he shouted, “Whatever the cost we will set the nation straight!”

The Downstate hospital protest made history for the high number of people arrested for disruptive acts of civil disobedience. On July 22nd over 1,200 people attended the demonstration and over 200 were arrested – 143 were arrested on July 23rd – 84 on July 25th. This was the largest mass arrest of African-Americans in New York since 500 people were jailed during the Harlem riots of 1943.

Daily news coverage of dramatic, heroic acts of civil disobedience and record numbers of arrest made the atmosphere at Downstate a magnet for activists from all over the city. Malcolm X attended the protest daily, but never participated in the demonstration. Some Brooklyn CORE members approached X and invited him to join the protest, but he declined because CORE's the picket lines were inter-racial. Malcolm X was quoted as saying, "I'd be only to happy to walk with you just as soon as you get them devil off the line." But Malcolm X’s presence helped shape the evolution of Brooklyn CORE and it’s militant nature, and tactics.

.jpg)

While at the demonstration, Malcolm X caught the eye of a young Sonny Carson, who was drawn to the Downstate protest because of the militancy and dramatic tactics of Brooklyn CORE. A former street hustler and member of a gang called the Bishops, Carson was fresh out of prison when the Downstate protest began. Meeting Malcolm X that day turned him into a political activist. Malcolm X approached him, shook his hand, and, according to Carson, "looked at me and said, you look like you can get something done." That inspired the young man to direct his energies and leadership abilities towards black nationalist politics and militant activism.

But Brooklyn CORE members’ non-violent tactics, bold spirit,

and strong camaraderie, which kept the Downstate protest alive, also appealed

to a rowdier elements of the Brooklyn community, and out of work black

tradesmen that neither CORE nor the ministers could control.

"We Struggled in Vain"

After just three weeks of protesting, some on the Ministers’

Committee felt they might no longer be able to control people in the crowds,

which increasingly became restless with the lack of support from the mayor’s

office and the amount of arrest. Many ministers wanted to end the protest because

they felt the demonstration was taking up too much of their time and causing

them to neglect their churches.

The ministers officially became the leaders of the campaign,

when they jumped the gun, and issued the following demand: Governor

Rockefeller, Mayor Wagner, and Building Trades Council President Brennan had to

make the workforce on all publicly funded construction jobs at least 25%

African-American and Latino. Brennan denounced the 25% demand as blackmail; his

only concession was to establish a six-man panel to screen job applicants.

The ministers wanted to negotiate while they still had some

influence with elected officials. They were looking for a way out of the

campaign that allowed them to save face with their political contacts and

church members. An opportunity came at the end of July.

During the last few days of July, as the demonstration

threatened to fizzle without any gains, some protesters wanted to employ more

destructive and violent measures to gain politicians’ and labor leaders’

attention. On July 31st, the picket lines at the Downstate

construction site erupted into a near riot. Teenagers from local high schools

started a new technique that day. Ten of them locked arms and blocked a truck

until police asked them to disperse, which they did. Quickly, after they left,

another ten appeared in their place. The crowd of about one-hundred

demonstrators spilled into the streets, scuffled with the police, and one

protester kick a cop in the groin, sending him to the hospital.

The incident on July 31st was the breaking point for the ministers, and they quickly began to distance themselves from Brooklyn CORE and began to aid the police in cracking down on militant protesters.

On

August 6th the ministers’ committee met with Governor Rockefeller

and dropped its demand for the quota, and three hours later worked out a

compromise that ended the campaign.

In exchange for an immediate end to the demonstration, the

governor agreed to appoint a representative to monitor the construction

industry and report cases of discrimination to the State Commission on Human

Rights. Rockefeller also promised a special investigation into charges of

racial discrimination against blacks. Last, a recruitment program would be created

to place qualified African-American and Latinos in unions and apprenticeship

programs.

Except for the promised recruitment program, nothing new had

resulted from the Downstate protest, and subsequent talks. Moreover, there was

no guarantee that the Building Trades Council or the union, which retained

their power to discriminate without penalty, would support the governor and the

ministers’ apprenticeship program.

The ministers’ held a rally that evening and announced their

victory. They invited Olive Leeds to speak and publicly endorsed the

settlement, which he did. Twenty-five years later, Leeds regretted his

decision, calling it “the biggest mistake I’ve ever made in my life.”

Logistically, Leeds realized that the demonstration was over

without the ministers’ political influence and support. “Basically, I felt what

the hell, I can’t carry it by myself,” he said. “CORE can’t carry it. The NAACP

isn’t anywhere. Urban League’s got no troops and the ministers are pulling out.

What’s left? There’s nothing. So I agreed to go along.”

Members of Brooklyn CORE it was still possible to win minimum

hiring percentages or at least push for some immediate hires. They accused the

ministers of selling out just when tangible signs of victory seemed possible.

CORE wanted to the protest to continue. Leeds put the question to a vote, and

the decision was unanimous. But, Brooklyn CORE could not generate the necessary

numbers after the ministers abandoned the campaign.

In many ways, the Downstate protest might seem like a

failure. The promised apprenticeship program failed to produce many jobs. After

the settlement, Gilbert Banks, a black labor organizer remembered that the

unions and politicians “got a construction team to review 2,000 people who

applied for these jobs. There were 600 who could do anything they wanted:

electricians, plumbers, carpenters, steamfitters; all that stuff. The deputy

mayor got this committee together, and two years later, nobody was hired. So we

had struggled in vain.”