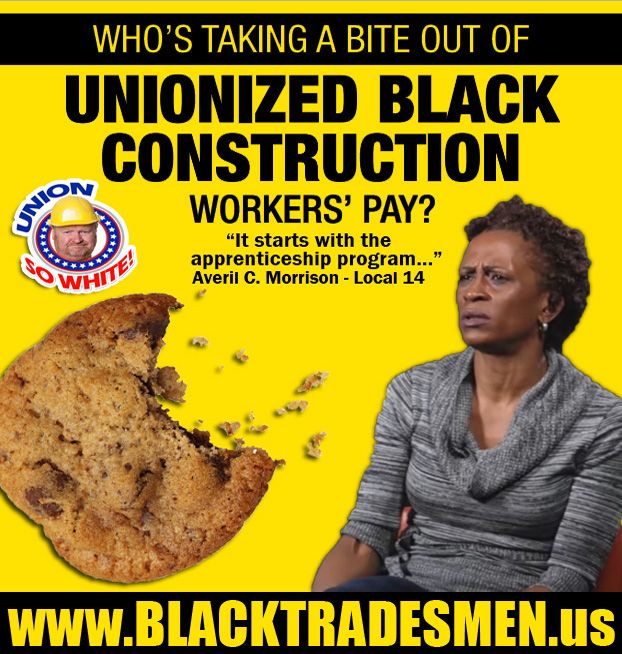

Black union construction workers earn less than white union members

We’ve reported the fact before that black construction union

members earn less on average than white union members. The unionized

construction workers in New York City specifically, earn 20% less on average

than their white co-workers performing the same trade. Through the

implementation of racial discriminatory hiring practices and Jim Crow ere

pre-apprenticeship programs New York City’s construction labor unions have

effectively maintained a 91% white male membership.

This is the story of Averil C. Morrison, a black tradeswoman,

who along with 4 other union operating engineers ( one black tradeswoman, 2 black

tradesmen, and 1 Hispanic tradeswoman) sued the International Union of

Operating Engineers Local 14-B—a AFL-CIO member union—for racial discrimination.

AVERIL MORRISON IN HER OWN WORDS

“As one of fewer than 20 minority females in the

1,600-member International Union of Operating Engineers Local 14-14B — one of

the city's construction unions — I know first-hand that our mostly white

membership book is not a coincidence. Rather, from my perspective, it appears

to be a direct consequence of the union leadership's actions to limit access

and opportunity for skilled workers who aren't white males.

In New York City, the Operating Engineers is considered an

elite construction union. Members operate bulldozers, backhoes, cranes and

other heavy machinery, and they're paid well for their work. Hourly pay and

benefit rates range from roughly $70 an hour for unskilled jobs to $120 an hour

for skilled positions. (Work that's done on weekends, holidays or overtime is

paid at double the base hourly rate.)

These are the jobs that helped build the middle class, and

it's easy to understand why workers of all racial backgrounds aspire to them.

Unfortunately, New York City's construction unions have historically kept these

opportunities from people of color. You can still find on city government's

website a copy of "Building Barriers," a report on racial

discrimination in the construction industry that was released in 1993.

The city's unions argue that they've improved since then,

and certainly they have. Some of these improvements were court-ordered. But

progress remains painfully slow. At the end of 1988, 9% of Local 14-14B's

membership was non-white; today that figure is roughly unchanged, in a city

that's 35% black and 27% Hispanic.

On a personal level, it's clear the problems that a black

woman like myself faced then still exist today.

It starts with the apprenticeship program, the pathway

through which a worker is supposed to learn the skills of their trade and move

on to full union membership. In my class, which was composed entirely of

minorities, we spent our time either sitting in the classroom or watching other

people work on equipment; I didn't receive on-the-job training until my second

year. But there's a loophole: If you're sponsored or referred by an existing

member, you can bypass the apprenticeship program and earn higher journeyman

wages on the job as you learn your skill.

Not surprisingly, friends and family of the existing white

membership are frequently beneficiaries of this loophole, while people of color

languish in an apprenticeship program with minimal pay and opportunity. It took

me nearly four years to "get my book" — a term used to describe full

union membership — and even then, it was only through persistent communication

with the gentleman running the training program. Other minorities aren't so

lucky.

Unions are supposed to create a level playing field for

workers, nowhere more so than in the hiring hall where work is assigned. The

hall opens at 6 a.m. every morning, and available jobs on any given day should

be distributed on a first-come, first-serve basis. Access to the longer-lasting

and better-paying jobs is supposed be a matter of luck. In reality, rising

early and having luck matter less than who you know and what color your skin

is.

I should know. I've spent too many mornings waking up at

2:30 a.m., commuting to the hiring hall, and standing outside for two hours

only to receive a low-paying job that lasts for a day or two — or no work at

all. Meanwhile, the good-paying jobs on long-term construction projects are

assigned far in advance, when the union's business agent parcels them out

overwhelmingly to connected white males.

In 2012, fed up with being treated as second-class citizens,

a few of my colleagues and I filed a discrimination complaint against our

union {The trial begin spring 2016}. We filed the complaint not just for

ourselves, but on behalf of other minorities who are skilled tradespeople but

are being denied the opportunity for good work on account of their skin color.

We're not trying to punish the union. We're trying to improve it.” - Averil Morrison, New York Daily News

According to Laborpains.org court findings revealed, the union (Local-14b) allegedly

allows its predominately white membership to refer new prospective members (who

are predominately white) as full journeymen, while requiring prospective

members without connections (who are more non-white) to do lower-paid

apprenticeships. The plaintiff union members allege that the largely white

referred new members get to skip apprenticeship even if they do not have “any

qualifications other than being sponsored by an existing White member.”

A brief review of Local 14-B’s wage scale shows just how big

a favor skipping apprenticeship all together can be. According to the 2015-16

apprentice wage scale, first-year apprentices are paid $29.25 per hour (40% of

the Pile Driver rate). By the end of a three-year apprenticeship, the wage

rises to 60% of the Pile Driver rate ($43.87/hour). Meanwhile, a full-member journeyman Pile

Driver is making $73.12 per hour.

There are further allegations of the union rigging job

placements in favor of white members. Using its control of the hiring hall

system of job referrals, Local 14-B allegedly manipulates the hiring hall so

that white members get jobs that last longer (which assures white members of

higher earnings and less time unemployed). Even more egregious, Local 14-B’s

absolute discretion for assigning “master mechanics” (essentially shop stewards)

ensures a racial wage gap, as master mechanics who are appointed are allegedly

“almost never” non-white. Master mechanics allegedly “can work virtually as

much double time as he desires” and “easily earn several hundred thousand

dollars a year.”