Understanding the obstacles black construction apprentices face in 2019 Pt.1

To provide context for this article, we briefly want to

describe a traditional state approved construction apprenticeship program. It

is important to note, however, there is significant variation in both the rules

and practices across different states apprenticeship programs. Overall the federal

Department of Labor regulates and supports apprenticeship programs.

Apprenticeship programs prepare individuals for careers in various trades (mostly

in construction) using a combination of on-the-job training and course work. For example, highway trades are a specific

subset of construction work that include trades such as laborers, equipment

operators, carpenters, and cement masons. This work is generally outdoors and

physically intensive. Apprenticeship programs may be union based (i.e., all

apprentices are members of a union and employers hire only apprentices from union

programs) or “open shop” (apprentices are not union members and work for employers

who hire nonunion workers).

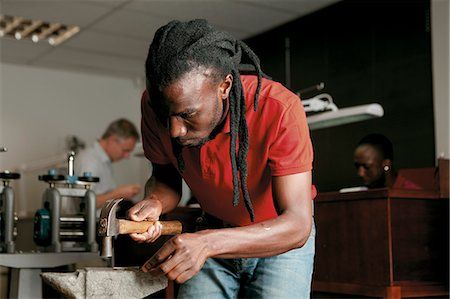

The American construction industry has traditionally been

marked as a very physically intense occupation and has largely been occupied by

white male workers. Although, black labor has always played a major role in the

construction of America, predating the founding of the United States, black men and black women entering the trades today experience racialized employment

practices during their apprenticeships.

It has been a well-documented fact that in the United States black tradesmen and tradeswomen have experienced harassment based on race/ethnicity

in the construction industry at appalling levels. As a black tradesman myself, who has completed a

construction apprenticeship, I would agree without exception that the hardest

part of working in the trades is not the job, but dealing with prevailing attitudes

about blacks not belonging in the trades, even at the union level.

DISCRIMINATORY

HIRING PRACTICES

Let’s discuss where the racial discrimination in the

construction hiring practice begins. A study by Roger Waldinger and Thomas

Bailey published in Politics and Society, titled “The Continuing Significance

of Race: Racial Conflict and Racial Discrimination in Construction.” argued

that black tradesmen have not attained significant inroads into construction

workforce because of the informal hiring and training practices and resistance

from unions.

In order to be accepted into an apprenticeship program,

individuals typically must be 18 years of age and hold a high school diploma or

equivalency certificate. Apprentices choose an apprentice program that will

train them in a specific trade. An apprenticeship program typically takes two

to five years to complete, depending upon the requirements of the program and

the availability of jobs. Yet, most union and non-union apprenticeship programs

do not advertise these openings in the black community nor do they conduct any outreach

programs in majority black high schools to recruit black youth.

While all apprentices are required to complete a set amount

of on-the-job training hours and course work, which differs by apprenticeship

program, the majority of apprenticeship programs training centers are often

located far from major black cities and suburbs. The distance an average black construction apprentice travels to training often creates a logistics issue. Some training centers are located more than 50 miles from black suburbs.

Apprentices attend classes ranging from basic math and

construction safety to specialized classes for their chosen trade. The

on-the-job training provides apprentices with hands-on experience under the

guidance of a journeyworker (a skilled craftsperson who completed an apprentice

program). Attaining the necessary training

on job sites is pivotal to apprentices’ success in the program and their ability

to become journeyworkers or journeyman.

And, since on the-job training is a critical counterpart to

classroom training, surmounting the racial discrimination and getting the

training is a necessity, yet an unnecessary burden for black apprentices. Aside

from the racist comments and graffiti which are so pervasive in modern American

construction culture, black apprentices also face ongoing issues with finding

work and being assigned to low-skill tasks.

In a study conducted by Kris Paap in a Labor Studies Journal

article, titled “How Good Men of the Union Justify Inequality,” found that black

tradesmen did not receive the informal mentoring on the job site that white tradesmen

received. In addition, black tradesmen were more likely to be perceived as lazy

or bad workers and they were more likely to be blamed when mistakes were made.

When a person applies to an apprenticeship program, they are

ranked based on various criteria, which varies from program to program.

Programs have an interview or a “point system,” which scores aspects of the

written application to document completed course work and previous work

experience. Some union apprenticeship

programs require the apprentice themselves to find an employer to write them a ‘Sponsorship

Letter’ which grants them entry into a labor union, upon paying entry dues.

The problem with this form of recruiting is many black

apprentice complain of discrimination while seeking sponsorship, and also complain

that their past work experience is often over looked and they are hired at

lower pay rates. For example, a tradesman or woman with 3 to 4 years of

documented work experience should be sponsored into the union as a Journeyman

or Journeywoman, but for many experienced black tradesmen with professional

experience this is not the case.

“I had 6 years of piping and plumbing experience but when I

entered the apprenticeship I was indentured in as a 1st level

apprentice, they tried to bring me in as a pre-apprentice, but I said hell naw.

A lot of guys with family connections, especially the white boys, come in as

Journeymen getting $38 an hour. I persevered and I’m a journeyman now.” - Jim, Journeyman Pipefitter, completed

program.

Those that do become sponsored or accepted into a

construction apprenticeship are put on an“eligible list” that determines the

order in which apprentice’s access jobs. As jobs become available with “training

agents” (employers associated with the apprenticeship program), applicants at

the top of the list are called and registered as apprentices. When apprentices

complete a job or are let go for any other reason by their employers, they are

put on an “out of work” list that ranks apprentices by time out of work (a

version of the out of work list is used by many, but not all, apprentice

programs).

As job opportunities arise, apprentices are called based on

the order of the list. However, as will be discussed below, construction

companies can circumvent the out-of-work list in order to maintain steady

employment with their “regular employees”.

While on-the-job training is a required part of

apprenticeship program, work is not always immediately available and jobs are

not guaranteed. One of the most prevalent issues effecting black tradesmen and

tradesmen is a lack of network, a network that they control, and a network that

they can depend upon for job opportunities. We will discuss this further below.

Construction is a cyclical industry and apprentices may be out of work for days, weeks, or months at a time. But, once the classroom work and on-the-job hours are complete, apprentices “journey out” and become journeyworkers or journeymen, who have the credentials, skills, and experience necessary to work in their designated trade at the highest pay scales. Journeymen can work unsupervised and are responsible for training new apprentices. They often go on to become foremen, supervisors, or superintendents.

There are many aspects of apprentice programs that are (on

the surface) equitable and race neutral: apprentices are accepted into programs

using standardized criteria; in some apprentice programs, jobs are assigned

using an out-of-work list; in some apprentice programs, employers are not

allowed to request specific apprentices; employers may not turn down black

workers or women; and apprentices at the same level are paid the same wage

(thus eliminating the possibility for a gender or racial/ethnic wage gap

between workers with equal experience). However, drawing on many studies we

examine how racial/ethnic inequalities still persist in apprentice programs,

despite these apparently race-neutral policies.

Today, across the United States, the construction workforce

as well as apprenticeships primarily consists of white males, and some states

have sought to diversify recently targeting funds intended to encourage “women”

and so-called “people of color” to enter into the trades; but no state has created

any programs that specifically increase retention of black workers, primarily

apprentices. Black apprentices across the United States remain a small portion of

new apprentices and there are continued issues with retention of these black men

and black women. As noted above, there are many aspects of apprentice programs

that are (on the surface) equitable and race neutral.

GOOD OLD BOYS CLUB

As stated above, the construction industry is a white male

dominated industry. In our study understood the apprenticeship system (and the construction

trades more broadly) to be a “good old boys’ club” (a combination of the

phrases “old boys’ club” and “good old boys”), that is, an occupation dominated

by working-class white men and built upon relationships among these men.

The experience of many black apprentices in the trades as a

“good old boys’ club” has resulted in subtle (and sometimes not so subtle)

exclusion and harassment. The discrimination that some black apprentices face

has damaged their access to relationships with journeymen, foremen,

supervisors, and other workers on their job site. This, in turn, has affected

their opportunities to be mentored and ultimately their ability to remain

consistently employed.

Apprentices are more likely to be successful if they are

able to remain more steadily employed, either by staying with a company and moving

from project to project (avoiding the out-of-work list) or by limiting their time

on the out-of-work list and finding work quickly after being layed off.

Statistically, across the United States black male

apprentices accrue fewer work hours per month than white male apprentices. Too

much time unemployed between jobs is a major factor that often deterred many black

apprentices from completing their apprenticeship programs. Many black

apprentices believe that the frequent layoffs are purposefully done to make it

difficult for black apprentice to compete.

Speaking under anonymity, a current black male union

carpentry apprentice told Blacktradesmen.us that, “I did everything right, I

passed all of my inspections, I showed up 30 minutes early everyday, I brought

my own water, I never got a safety violation, but they two checked me. I just

did my job, but that wasn’t enough, with all the stupid black jokes they made

it wasn’t worth it.”

Two checks meaning ‘layed off’, an expression used throughout the construction industry on describing how a foreman or superintendent fires a tradesman by providing him with both of his payroll checks, severing all relationships.

One specific problem that some black apprentices face in the course of their on-the-job training, they did not have opportunities to learn all the varied skills they needed to be successful journeymen, as a challenge to completing their apprenticeship. While some studies show, black workers were the most likely to identify doing repetitive or low-skill tasks, while white men were the least likely of all groups to be assigned repetitive or low-skill tasks (such as cleaning the site or flagging traffic).

YOU’RE NOT LAZY!

The legitimacy of a lack of black apprentices in the trades

is bolstered by a reliance on the belief that success is primarily due to hard

work. While apprentices articulate the many challenges that they face, when

specifically asked why some apprentices do not succeed in their apprenticeship program,

“not working hard enough” or “being lazy” were consistently given as the

primary reason by apprentices. But the perception

of who “workers harder than others” is often bias based upon racial stereotypes.

“Head down, ass up. Pretty much. They just got to stay at

it. You can’t be lazy about it. You have to stay working, you have to stay

busy.” (Dave, Black male, completed apprenticeship)

Apprentices with a “poor work ethic” or perceived as working

not as hard as others on the job site, or those that would not (or could not)

learn the necessary skills, and those who had a bad attitude at work are most

often equated with being “lazy.” The stereotypical label of “laziness” has plagued

black workers since slavery, and is one of the most prevalent stereotypes used

against black workers today.

BUILD A NETWORK

The importance of black tradesmen and tradeswomen to network

and build strong relationships amongst one another is key to their success. The

lack of network and industry connection has made things harder for black

apprentices who are frequently out of work. The lack of a brotherhood outside

of the “union brotherhood” is missing for black tradesmen and women. Since

forever, networking in construction is an essential aspect you must develop.

Relationships and connections within an apprentice’s network

are important to have more opportunities to advance their careers. Attending union

meetings and social events are also important apprentices seeking to advance

their industry connections. www.blacktradesmen.us

is also a great tool to connect with people in their field.

The pervasive harassment (particularly racial discrimination) that black Americans in construction face as well as the strategies they use to respond to negative experiences at work is hurting black tradesmen and women fighting to complete construction apprenticeship programs and reach the status on Journeyman or Master level professionals. The lack of an internal network can exacerbate this condition for black apprentices.

We hope that our on going research adds to an understanding of

how organizational policies and discriminatory practices, are causing in racial

inequalities in construction work organizations

In exploring the experiences of black apprentices, we contribute to an evolving understanding of how apprenticeship programs across the United States works. Through assessing these processes, we hope to contribute to conversations about the changes in the construction industry as well as broader policy debates aimed at addressing racial/ethnic inequality in the industry.