50 years after the Kerner Report Black workers are still racially disadvantaged

Economic Policy Institute - The year 1968 was a watershed in American history and black

America’s ongoing fight for equality. In April of that year, Martin Luther King

Jr. was assassinated in Memphis and riots broke out in cities around the

country. Rising against this tragedy, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 outlawing

housing discrimination was signed into law. Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised

their fists in a black power salute as they received their medals at the 1968

Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Arthur Ashe became the first African American

to win the U.S. Open singles title, and Shirley Chisholm became the first

African American woman elected to the House of Representatives.

The same year, the National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders, better known as the Kerner Commission, delivered a report to

President Johnson examining the causes of civil unrest in African American

communities. The report named “white racism”—leading to “pervasive

discrimination in employment, education and housing”—as the culprit, and the

report’s authors called for a commitment to “the realization of common

opportunities for all within a single [racially undivided] society.”1 The

Kerner Commission report pulled together a comprehensive array of data to

assess the specific economic and social inequities confronting African

Americans in 1968.

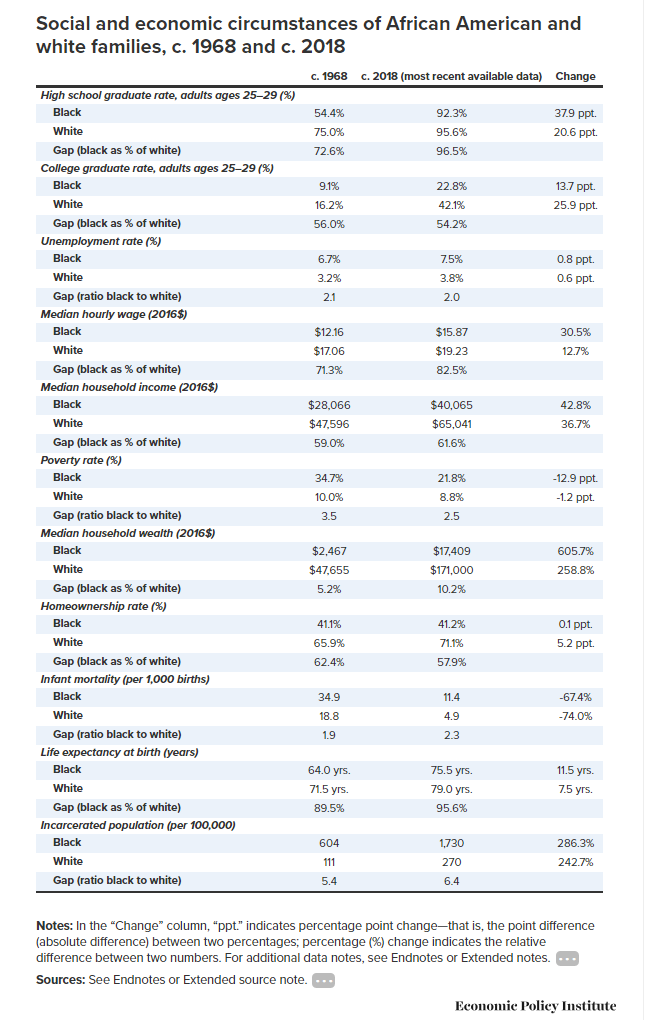

Where do we stand as a society today? In this brief report,

we compare the state of black workers and their families in 1968 with the

circumstances of their descendants today, 50 years after the Kerner report was released.

We find both good news and bad news. While African Americans are in many ways

better off in absolute terms than they were in 1968, they are still

disadvantaged in important ways relative to whites. In several important

respects, African Americans have actually lost ground relative to whites, and,

in a few cases, even relative to African Americans in 1968.

Following are some of the key findings:

· + African Americans today are much better educated than they were in 1968 but still lag behind whites in overall educational attainment. More than 90 percent of younger African Americans (ages 25 to 29) have graduated from high school, compared with just over half in 1968—which means they’ve nearly closed the gap with white high school graduation rates. They are also more than twice as likely to have a college degree as in 1968 but are still half as likely as young whites to have a college degree.

+ The substantial progress in educational attainment of

African Americans has been accompanied by significant absolute improvements in

wages, incomes, wealth, and health since 1968. But black workers still make

only 82.5 cents on every dollar earned by white workers, African Americans are

2.5 times as likely to be in poverty as whites, and the median white family has

almost 10 times as much wealth as the median black family.

+ With respect to homeownership, unemployment, and incarceration,

America has failed to deliver any progress for African Americans over the last

five decades. In these areas, their situation has either failed to improve

relative to whites or has worsened. In 2017 the black unemployment rate was 7.5

percent, up from 6.7 percent in 1968, and is still roughly twice the white

unemployment rate. In 2015, the black homeownership rate was just over 40

percent, virtually unchanged since 1968, and trailing a full 30 points behind

the white homeownership rate, which saw modest gains over the same period. And

the share of African Americans in prison or jail almost tripled between 1968

and 2016 and is currently more than six times the white incarceration rate.